Section Branding

Header Content

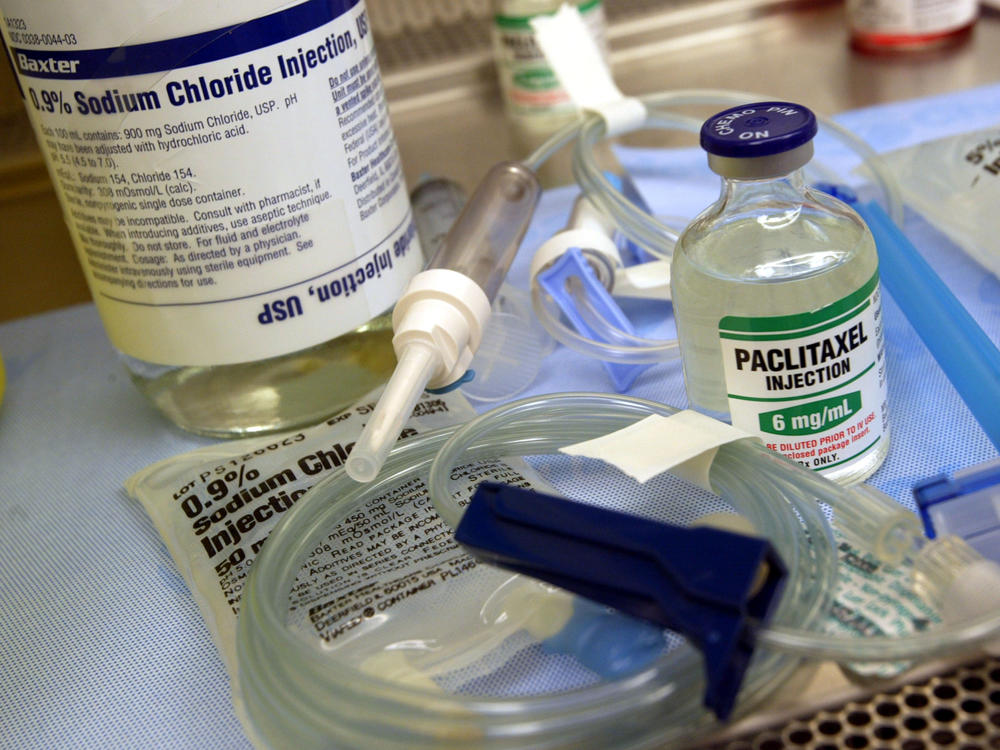

Oncologists' meetings with drug reps don't help cancer patients live longer

Primary Content

Pharmaceutical company reps have been visiting doctors for decades to tell them about the latest drugs. But how does the practice affect patients? A group of economists tried to answer that question.

When drug company reps visit doctors, it usually includes lunch or dinner and a conversation about a new drug. These direct-to-physician marketing interactions are tracked as payments in a public database, and a new study shows the meetings work. That is, doctors prescribe about five percent more oncology drugs following a visit from a pharmaceutical representative, according to the new study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research this month.

But the researchers also found that the practice doesn't make cancer patients live longer.

"It does not seem that this payment induces physicians to switch to drugs with a mortality benefit relative to the drug the patient would have gotten otherwise," says study author Colleen Carey, an assistant professor of economics and public policy at Cornell University.

For their research, she and her colleagues used Medicare claims data and the Open Payments database, which tracks drug company payments to doctors.

While the patients being prescribed these new cancer drugs didn't live longer, Carey also points out that they didn't live shorter lives either. It was about equal.

The pharmaceutical industry trade group, which is known as PhRMA, has a code of conduct for how sales reps should interact with doctors. The code was most recently updated in 2022, says Jocelyn Ulrich, the group's vice president of policy and research.

"We're ensuring that there is a constant attention from the industry and ensuring that these are very meaningful and important interactions and that they're compliant," she explains.

The code says that if drug reps are buying doctors a meal, it must be modest and can't be part of an entertainment or recreational event. The goal should be education.

Ulrich also points out that cancer deaths in the U.S. have declined by 33 percent since the 1990s, and new medicines are a part of that.