Section Branding

Header Content

Liberty County commission takes over sheriff’s school zone speeding fines account

Primary Content

Robin Kemp, The Current

The Liberty County Board of Commissioners has taken control of a bank account that Sheriff Will Bowman established in 2022 to hold school zone camera ticket revenues. As of April 14, according to county records, the account has brought in $1,100,808.80 since its inception.

The tentative agreement, which could change before a final vote, also distances the county from any liability related to how the sheriff spends those funds, while requiring Bowman to seek county approval for any such spending.

The board had Liberty County Attorney Kelly Davis draft the agreement after Bowman presented $20,000 to Bradwell Institute towards the costs of its band traveling to perform in the national Fourth of July parade this summer, as well as $2,368 to a local AAU youth basketball team for new uniforms. Photos of the presentations on social media prompted a closer look at how Bowman was spending the funds.

As of March 28, the account balance was $320,633.43, according to account activity the county provided to The Current. That’s after $667,054.52 in checks were written between June 22, 2022 and March 27 of this year.

The county’s finance department has had view-only access to the account’s transaction records dating from their inception.

The board’s takeover comes amid a hotly contested sheriff’s race and after a months-long tug-of-war over the fund. The commission, which manages the county’s finances, has a fiduciary responsibility to protect county funds. Bowman, as an elected constitutional officer, does not report to the commissioners but does submit LCSO budget requests to the board for approval.

Terms of the proposed deal

Specifically, the agreement with the camera company, RedSpeed, would limit such spending to four broad categories:

- “Vehicles, equipment, and other tangible personal property used by the Sheriff for his Office”

- “Rental payments or other contractual payments for facilities, services, software, and other property for the direct benefit of the Sheriff’s Office”

- “Improvements to property and facilities occupied or utilized by the Sheriff’s Office”

- “Training and certification for the Sheriff’s employees”

It also would allow Bowman to dedicate up to 20% of revenues to the Liberty County School District “to help defray the costs of the School Resource Officer program and other public safety initiatives implemented by the Sheriff for the benefit of local schools.”

The “personal agreement between the parties” would give the commission sole discretion to terminate the agreement and “assume exclusive control of the Program Account and Program Funds,” although either side can give 90 days’ written notice to terminate. If either side doesn’t like the agreement, they can try to settle the dispute in a timely fashion or take it to court. In either case, the funds would be frozen until the issue is resolved.

At the April 18 board meeting, which Davis attended by phone, commissioners voted to table final action on the proposed agreement until they could read it in depth. County Administrator Joey Brown told commissioners that debit cards for the account had already been turned off. Although the memorandum of understanding with RedSpeed had not yet been signed, Brown said that the county would take over the account at Ameris Bank the day after the meeting, removing two Sheriff’s Office employees, Major Bill Kirkendall and Brittany Cook, as cosigners and replacing them with Commission Chairman Donald Lovette and Brown.

The board approved a committee, which Brown told The Current would meet “to gather data only,” to include Assistant County Administrator Joseph Mosley, Chief Financial Officer Samantha Richardson, and a representative of the sheriff’s office.

Clarifying the fund's auditing

Brown also told the commission on April 18 that the RedSpeed account had not been audited, which former Liberty County Chief Financial Officer Kim McGlothlin, who is running for tax commissioner, told The Current was not accurate.

“It’s always been part of the annual audit that the county has every year that we publish,” McGlothlin said. “It’s always been part of it. So that was definitely misleading, and a misstatement.”

McGlothlin said that a fund can be audited to make sure all the numbers match, which she said has been the case all along. That process is a financial audit, she explained. A fund also can be audited to see whether the spending followed the rules that apply to a particular account, which she said was a compliance audit.

The difference is that a financial audit is “not looking to see ‘is this legally correct?’ What they’re looking to see is ‘did this expenditure go through the bank?’ And if it did, did it get captured in the general ledger?… It’s literally keeping the books. It’s not like making an evaluative judgment. It’s just saying this number matches this number.”

A compliance audit, on the other hand, is when the county “present[s] our financials to the [outside] auditors to audit, and tell them, ‘Yes, everything has gone through the proper process. Everything’s been vouchered properly, everything’s been requisitioned properly. Here’s our fixed asset listing… you can test all of that.”

Because the RedSpeed account has “very specific guidelines,” she added, “I don’t think the average [outside] auditor would even know…. to check if the expenditures are legal. That’s not what they’re doing. So that’s a little misleading. Very misleading.”

Asked to clarify his remarks, Brown concurred with McGlothlin’s descriptions of financial and compliance audits.

“The RedSpeed account was ‘booked’ on the ledger each month by the CFO, who simply took the balance in the account and made the entry,” Brown told The Current. “The assumption by some folks is that these ‘financial’ audits also include a check on legal compliance regarding use of the funds which they do not. A special or separate ‘compliance’ audit would need to be engaged for those purposes. I knew the [April 18] question on ‘audited’ really referred to the latter, which is where the concern has been, hence my answer.”

Any compliance audit “would be up to the board to decide,” Brown told The Current.

How the cameras got here

In 2021, Bowman entered into a contract with RedSpeed, a company that offers free speed zone cameras to local governments and law enforcement agencies as a revenue source. The tickets are civil penalties that do not add points to drivers’ records.

Under the tentative agreement, a draft copy of which The Current received from Brown, Bowman would be required to submit all spending requests from the fund to the commission for approval or denial. Brown said the draft could change before it is finalized.

It specifically distances the county and its “officials, employees, accountants, or agents” from any liability for Bowman’s spending decisions, “except that the County shall have the authority, but not the obligation, to confirm that the purpose and use of any disbursement, as stated by the Sheriff in requests to the County…is consistent with” state law about school speed zone camera revenues.

That draft reads in part, “It is the position of the County that the Board of Commissioners, as the ‘governing body’ under O.C.G.A. § 40-14-18, is authorized to assume exclusive control of the Program Account and determine which law enforcement and public safety initiatives should be funded” and that the agreement is “an effort to resolve competing positions of the parties and ensure that the School Zone Camera is administered in a transparent and efficient manner consistent with applicable law.”

That law details how and when school zone speeding cameras are to be used and how local law enforcement agencies or governments can spend any ticket revenues. The last part of the law reads, “The money collected and remitted to the governing body…shall only be used by such governing body to fund local law enforcement or public safety initiatives.”

What constitutes an “initiative” is not clearly defined in the law. However, the law does state that the fine is to be paid “to the governing body of the law enforcement agency,” and that the law enforcement agency or “an agent working on behalf of a law enforcement agency or governing body” — such as RedSpeed — sends out the ticket, which contains “a certificate sworn to or affirmed by a certified peace officer employed by a law enforcement agency authorized to enforce the speed limit of the school zone.”

In order to place the cameras in school zones, local school systems must apply to the Georgia Department of Transportation for a permit. An unsigned contract between Bowman and RedSpeed supplied by the Liberty County School System shows Superintendent Franklin D. Perry signed two GDOT permit applications to place RedSpeed cameras on April 19, 2021.

Who benefits?

Bowman, who was not present at the April 18 board meeting, told The Current that the sheriff’s department has an agreement with the Liberty County School System, under which LCSO can spend 20% of revenues on what he said are “school initiatives.” The copy of the agreement The Current received did not indicate that either the commission or the Liberty County School System are parties to the contract. However, the new draft agreement between Bowman and the county specifies that the sheriff can put in a request to the county for “up to 20% of Program Funds to the Liberty County School District to help defray the costs of the School Resource Officer Program and other public safety initiatives implemented by the Sheriff for the benefit of local schools.”

The sheriff’s department provided a PDF document listing the RedSpeed revenue account’s deposits and expenditures from January 2023 to April 8 of this year in response to an Open Records Request, but declined to provide a spreadsheet. The list included obviously law enforcement-related items like badges, radar units, and tint meters, as well as FBI-LEEDA leadership training and lodging expenses for Major Kirkendall, Major Krumnow, and Major Melvin. It also shows $5,000 to the Sheriff’s Office Benevolence Fund for “community outreach projects,” $314.36 for “Liberty/Bradwell Trophies,” $1,385 to Bakers Sporting Goods for “LCHS Hoodies,” a total of $1,099.11 spent at Walmart, Costco, and Food Lion for “Thanksgiving Community Engagement,” $137.83 at Walmart for “Deployed Military Care Packages,” $1,832 to MFAC, LLC for “HS Track and Field Supplies,” $2,358.16 to All American Specialties for “HS Jerseys,” $10,000 to “Phenom Elite Team” for “HS Football Clothing,” $680 to Foster Specialty Floors for “HS Sweat Mops,” $2,268.52 to 4Imprint for “Community Outreach Projects,” $3,517.88 to Baker’s Sports for “HS Basketball Equipment,” and $20,000 to LCBOE for “Liberty County Board of Education” — ostensibly for Bradwell’s band trip. Those expenditures came to $48,592.86.

The Current has left email and phone messages with RedSpeed seeking more details about the original contract. RedSpeed has not responded to those requests for comment.

County commissioners wrangle

Commissioner Gary Gilyard has been pushing the board to take control of the fund, saying the revenues are public money and should not go to particular schools or teams handpicked by Bowman. Gilyard, who brought up the RedSpeed revenues before the commission in June 2023, had cited a Savannah Morning News story about Chatham County school zone speed camera revenues topping half a million dollars.

A list of RedSpeed account expenditures that The Current received from the sheriff’s office through an Open Records Request did not show any expenditures on community or school initiatives before Gilyard had brought up the matter last June.

At the April 18 meeting, he said he was “excited” about the draft agreement because “it brought the oversight of the account back to the county, and it talked about that we being the governing authority, and it made me think that that’s the way it should have been all along.”

Gilyard told The Current that “law enforcement or public safety initiatives” are not a gray area of the statute, even though “initiatives” might not preclude an argument, however tenuous, that funding local youth activities as a means of keeping kids out of trouble could be seen as a form of community policing.

Commissioner Marion Stevens, a staunch supporter of Bowman who appeared alongside him at the Bradwell Institute band check presentation, has repeatedly alleged that the commission held an “illegal” executive session without Davis present. Neither Stevens nor Davis have responded to The Current’s requests for clarification about the substance of that meeting, which would be open to public scrutiny under the Georgia Open Meetings Act if it had not been a valid executive session.

Stevens also has asked repeatedly why the sheriff and not any other constitutional officers in Liberty County — including the tax commissioner, probate court judge, and clerk of superior court — have come under scrutiny for their spending.

In sometimes-elliptical public discussions about the controversy during the April 9 board meeting, Commissioner Eddie Walden told the board he had called for the point of order to go into that meeting, “to let this board know my findings, whether it’s true or false is a little bit muddy with some folks, that I retained my own attorney. So I have my own attorney that will be looking at it instead of just the county attorney. That was the legal matter that I wanted everybody to understand. That’s the reason I called for executive session. So there was a legal matter and I have retained my attorney.” Walden added, “I didn’t know that we had another constitutional officer that was misusing tax dollars. I mean, any way around it, that wasn’t the reason I called for the meeting. I heard that there was some issues out here, I had gotten phone calls, and I wanted to make sure that I had my own attorney, because I’ve been through one of these before.”

When the matter came up for a vote that night, Commissioner Connie Thrift complained that she had not gotten a copy of the proposed agreement until right before the meeting, and questioned why the board was considering a vote on something it had not had at least 24 hours to review. The board tabled the vote on the final agreement until its next meeting in May.

After the meeting, The Current asked Chairman Donald Lovette whether the school band or athletic teams would have to return the $20,000 to the RedSpeed account. He said they would not.

Previously, Lovette had told The Current he did not want to comment prior to the board’s expected April 18 vote. But on April 17, Lovette took part in an extended Facebook Live discussion of the matter with another elected official, School Board member Marcus Scott IV, who is running unopposed for the District 2 seat on the May 21 ballot.

During that discussion, Lovette said, “The sheriff is a constitutional officer. He stands by himself…. Their funds run through us. We are the fiduciary for them, their funds run through us, but operations, how they run, that’s all independent.”

Lovette explained that the county collects taxes and the constitutional officers “submit their budgets to us, but we don’t dictate how they run. So when the sheriff made that deal, whatever the word is, that’s between him and the school board.”

Whose lane is it?

Yet the draft agreement shows the board is trying to manage the sheriff’s discretionary spending in ways that the Georgia Supreme Court has frowned upon in past cases.

An Association of County Commissions of Georgia handbook on constitutional officers — like sheriffs — notes that county commissions and constitutional officers walk a delicate balance. Commissions approve the constitutional officers’ budgets, but constitutional officers, who are elected officials, “are not employees of the commissioners and are not subject to supervision by the board of commissioners.”

And if commissions try to get back at a constitutional officer by, for example, making politically-motivated budget cuts, according to ACCG, “The Georgia Supreme Court has stated that it will only reverse the board of commissioners’ budget decision if ‘it is clear and manifest’ that the board…abused their discretion in establishing a budget….There is a fine line between providing what the board of commissioners believes is a reasonable budget and dictating to a constitutional officer how to perform his or her statutory duties.”

However, making donations to community organizations — no matter how noble the intention — is not one of the Georgia Constitution’s required duties for sheriffs, who are primarily tasked with serving court papers, maintaining the jail, keeping arrestees safe, and preserving order at polling locations.

Timing is everything

The board’s takeover attempt comes amid a contentious sheriff’s race. Some of Bowman’s opponents who were present at the April 18 board meeting told The Current they want to see legal action taken against the sheriff. They say the RedSpeed money belongs to the taxpayers and should not be handed out arbitrarily.

“The only way that they kept talking about this, in listening to the whole thing, was ‘from here going forward,’” Kevin Hofkin said, “and that’s fine. But I would look at it from here going back. He spent the money, but has the money been returned? That’s what I want to know….That money needs to come back.” In 2021, Hofkin retired from the sheriff’s office.

Gary Eason, who retied from the sheriff’s office in 2022 and now works for the Bryan County Sheriff’s Office, told The Current, “You heard the law in there. It’s for law enforcement and public safety. None of those are for law enforcement. The golf carts that he got, yeah, you can use those as far as public safety, SROs can use them around the school. That’s fine. But don’t be taking it to a golf tournament.”

Eason added, “Let the people investigate it. If [Bowman] comes out clean, he comes out clean. I ain’t gonna throw no mud on him. And you know, I’ve known him for years, but some things is right, some things is wrong.” He added that the BOC is “trying to put it off, and I think they’re trying to put it off long enough because of the election coming up.”

James Ashdown, whom Eason introduced as his “future chief” deputy, said, “My concern is the GBI [Georgia Bureau of Investigation] should already be involved now, and the DA…. At minimum, you have a grand jury that’s convened every year. There’s one going on right now. They should send it to the grand jury. Let those people on the grand jury go through it.”

The GBI, which can only take up an investigation of this kind at the request of municipal governing officials, district attorneys, sheriffs, Superior Court judges, large municipal or county police chiefs, or the governor, told The Current it has received no such request regarding Bowman.

Hofkin, Eason, and Ashdown all have worked for the sheriff’s office, as have Gary Richardson and Keith Jenkins. Bowman, who from 2005 to 2019 served with the Georgia State Patrol, is the only candidate in the race who came to LCSO from outside the agency.

Bowman: ‘Accountable for everything that I do’

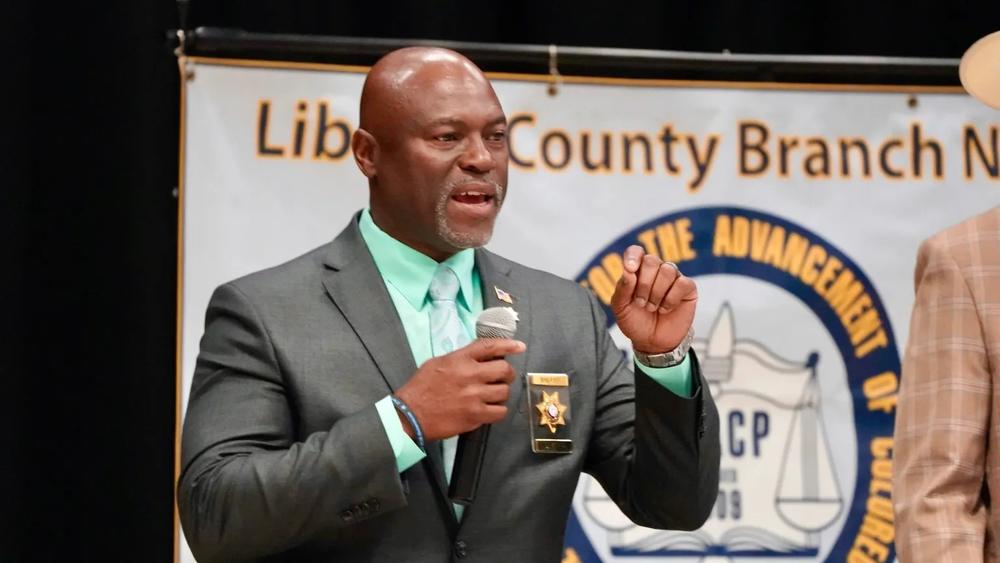

Bowman told The Current last week that his record as a public servant is impeccable and that he is concerned only with “doing the right thing.”

He pointed to his service as a senior noncommissioned officer with the Army and with the Georgia State Patrol. He also said that he resented recent news reports focused on the Bradwell Institute donation. But he added that he was reluctant to trash his opponents.

At the April 20 Liberty County Democratic Committee’s candidate breakfast, Bowman brought a bit more fire to his own defense, speaking directly to his reputation and challenging anyone to compare his background with those of other sheriff’s candidates.

“I will never do anything to disgrace this county,” Bowman said. “I was accountable for everything that I do. I have a flawless military career. I have a flawless Georgia State Trooper career. I am well known across this state. And even other states. I am well respected in the Georgia Sheriffs Association. So when anybody tries to attack my character, they’ve got to pick another route….I will go face to face anywhere, anytime with any candidate that’s running for sheriff. Talk about character. When you look at their background, I guarantee you’re not going to like what you see. When you look at mine, I can guarantee you, you will be like, ‘Man, there’s no way this guy is this good.’ So all that stuff that’s going on — trust me. I’m not gonna do anything wrong.”

Bowman also hinted at Liberty County’s tendency to go along with its established political network and said he opposes “‘doing it the way we always did it.’ I’m not that type of guy. If you’re looking for that type of guy, then you need to get with the other guy that’s running for sheriff. I’m not that guy. I can think on my own.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current.