Section Branding

Header Content

In Brunswick, drug cops were convicted. A prosecutor was indicted. But hundreds caught in their maw are forgotten

Primary Content

Caitlin Philippo, The Current

Additional reporting by Jake Shore, Maggie Lee and Margaret Coker/The Current

BRUNSWICK, Ga — On a winter afternoon in 2017, Mindy Lynn Johnson, a mother of two young children, was arrested at a budget hotel off I-95 in Glynn County and accused by the celebrated narcotics squad of selling methamphetamine to a female confidential informant.

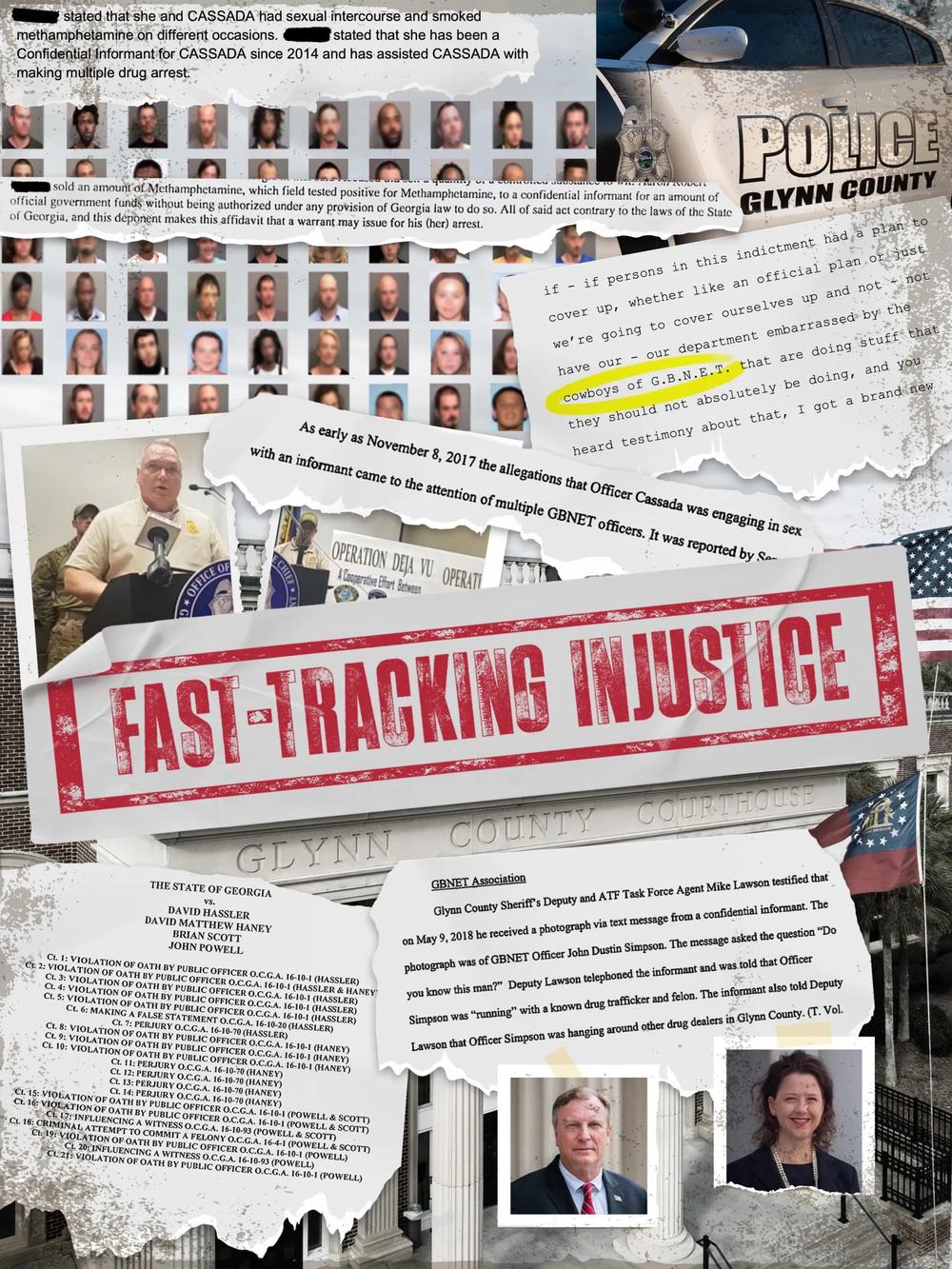

The informant, a frequent drug offender identified in police records as “CI 13-NCI-014,” was doing more than helping the Glynn-Brunswick Narcotics Enforcement Team (GBNET) capture illegal drug users and traffickers. That year, she was having frequent sexual encounters with her handler, Officer James Cassada, according to law enforcement records. Cassada also pressured her into buying meth and cocaine for his personal use and together the pair frequently smoked meth.

Unaware of these rampant violations of police procedure and unable to afford bond after her arrest, Mindy Lynn languished in jail for six months before finally agreeing to plead guilty. It was her first offense, but she was sentenced to 15 years, the first three to be served in prison.

Mindy Lynn is one of more than 450 people whose drug-related convictions were flagged five years ago by the former Brunswick area district attorney for possible review because of wrongdoing by GBNET officers. Yet analysis of thousands of records by The Current suggest that she, and scores of others, were never informed of this opportunity — and the officers of court who have the authority to decide whether their convictions were based on tainted evidence have ignored the issue.

The GBNET scandal, which broke open in 2019, is emblematic of the far-reaching consequences when corrupt police behavior goes unchecked for years. It also offers a sobering look at how Glynn County chose to treat the cops who were charged and convicted and the defendants caught in the maw of the unit that arrested hundreds of people per year.

For years GBNET officers relied heavily on confidential informants in cases involving alleged drug sales, while prosecutors took advantage of a backlog in drug lab analysis, as well as an overburdened public defender’s office, to fast-track hundreds of defendants into plea deals, according to The Current’s investigation. That situation kept defense attorneys in the dark about evidence against their clients, and records that would shed light on the scandal have been erased or are being withheld.

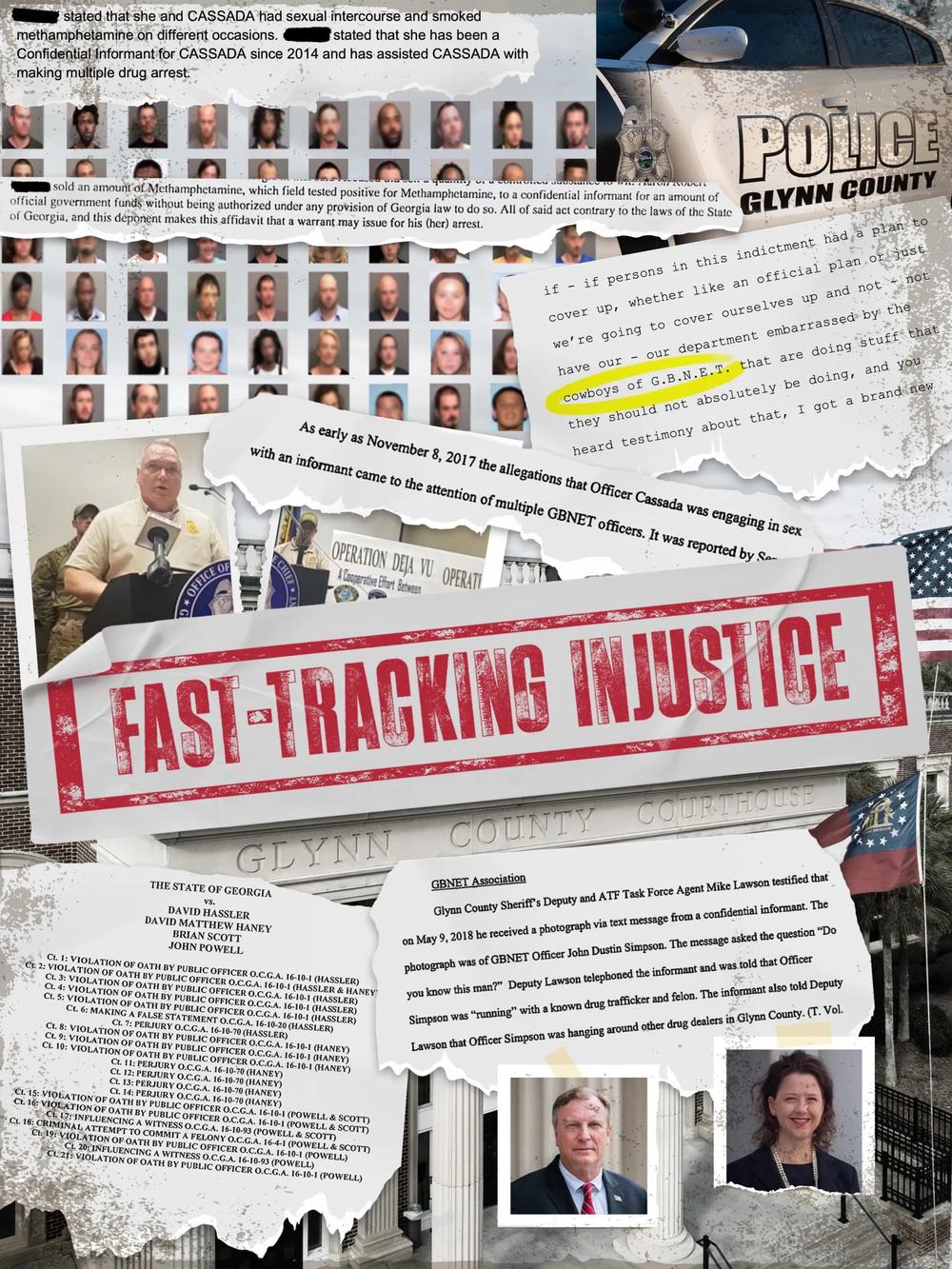

That any of the story can be told is partly the result of an unusual ruling in March 2019 by Glynn County Superior Court Judge Roger B. Lane.

Lane presided over hearings in which a Brunswick resident, Gary Whittle, was seeking to withdraw a plea deal after his arrest for allegedly selling cocaine. Those hearings were the first public indications that GBNET was rife with misconduct.

Officer Cassada had arrested Whittle, and he was also having sex with the informant whose testimony was key in Whittle’s arrest. Other members of the unit were alleged to have covered up these misdeeds, to have fraternized with felons, and violated police policy meant to ensure standards of evidence were unimpeachable.

The information was so incendiary that Judge Lane ordered the compilation of lists of cases spanning a two-year period worked on by five GBNET officers, including Cassada, and three confidential informants.

By the summer, Cassada had pleaded guilty to two felonies. Lane, meanwhile, had ruled all five officers tainted witnesses. Veteran prosecutors and criminal law experts said that ruling should have prompted automatic reviews of each of the officers’ cases, and convictions related to their police work should have been tossed out.

Jackie Johnson, the Brunswick Judicial Circuit district attorney at the time, chose a different path.

Her office compiled three lists of approximately 511 cases that she said were responsive to Judge Lane’s order. The charges were dismissed against Whittle. Then, in a brief spurt of judicial activity, charges affecting 14 other individuals on the lists were dismissed, based on Lane’s ruling that those convictions were riddled with constitutional violations.

In the months that followed, Glynn County elected a new district attorney and hired two new police chiefs. A different judge approved plea deals for two former GBNET officers. Meanwhile, the lists of potentially problematic cases were essentially forgotten — until The Current discovered them during a 15-month investigation.

An analysis of thousands of pages of court and GBNET records reveals that the DA’s office did not respond fully to Judge Lane’s order. The three lists focused primarily on Cassada, although the judge had called for an index of cases in which five named GBNET officers acted as the primary investigator "or in concert with one another" from January 2017 through February 2019. The DA’s office did not give the same attention to the other four cops, according to the documents.

At least four cases on the lists shared the same criteria cited in Judge Lane’s ruling that led to Whittle’s charges being dropped, including the use of the same tainted informants and police officers. The Current reviewed an additional 50 cases on the lists that were based on police work involving those same five police officers and different confidential informants.

Despite the similarities to the Whittle case, the prosecutors did not contact these individuals for the possibility of legal relief.

Additionally, The Current found four GBNET convictions that appear to be responsive to Judge Lane’s order that involved two of these named officers and used confidential informants. They, however, were not included in the index of cases.

Prosecutors are officers of court tasked with ensuring justice is carried out, and they are ethically bound by the rules of the American Bar Association and Georgia law to follow up when they know that witnesses have lied or been impeached. “Ethical rules state that prosecutors are not one-sided advocates seeking only to secure convictions,” according to Elizabeth Taxel, the director of the Criminal Defense Practicum at University of Georgia Law School. “Prosecutors must ensure that defendants are afforded due process protections, and that guilt is decided by sufficient and sound evidence. Prosecutors should take special precautions to ensure that innocent people aren’t convicted by conducting their own, thorough investigation with the goal of determining the truth.”

“Our legal system seems to value efficiency and finality above fairness to a troubling degree. Once an individual is convicted, it is very difficult to undo it.” Taxel said.

Former DA Jackie Johnson did not respond to requests for comment. John Johnson, her former chief deputy prosecutor and no relation to the district attorney, said that her office reviewed the list of cases ordered by Judge Lane with the intent of keeping as many convictions intact as possible.

It is unclear whether Judge Lane knew that much of his original order was not fully met. Judge Lane did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Current Brunswick District Attorney Keith Higgins, who is running for re-election against John Johnson, said he does not have the resources to proactively reevaluate the past GBNET convictions. “That’s just impossible,” he told The Current, referring to reopening closed cases. “I have seven prosecuting attorneys. They’re in court more days, in any given month, than they’re not, in terms of just handling the active cases.”

They don’t have “the time to go back and look at cases that were resolved before we were even here,” he said, adding that he should not be responsible for decisions made by his predecessor.

Wrongdoing that couldn’t be hidden

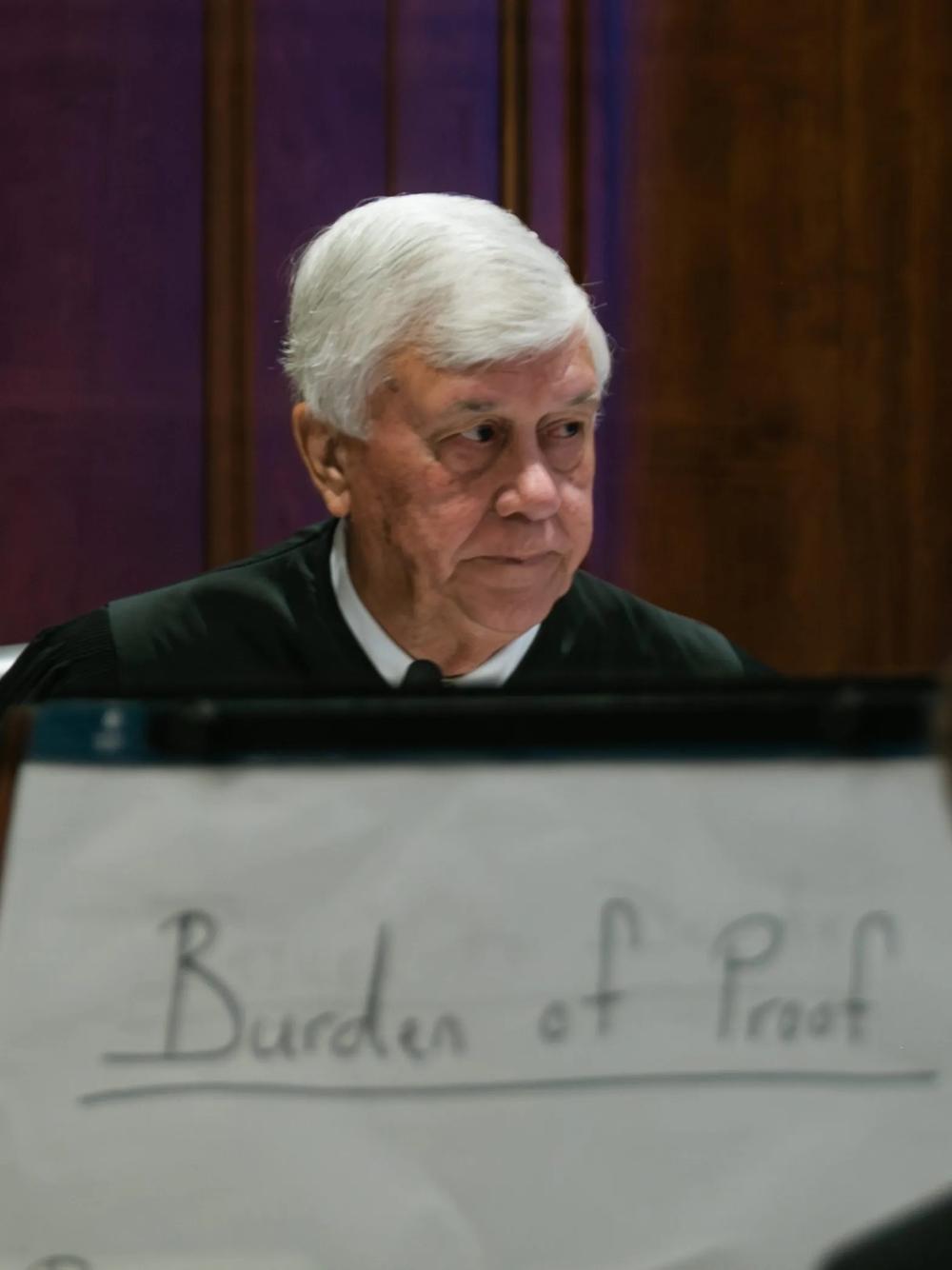

In the summer of 2019 Glynn County police and the DA’s office were battling a scandal unlike any they had ever faced.

With its frequent raids and arrests, GBNET had been championed and celebrated by Glynn County Police and county leaders as tough on crime. Yet internally some officers described the unit as operating with a cowboy culture. As the scandal unfolded, prosecutors who had spent years burnishing their conviction rates with GBNET’s arrests now faced a dilemma: Investigating cops could tarnish their professional records.

DA Johnson’s office focused on the wrongdoing that could no longer be hidden. Cassada had admitted to a drug and alcohol addiction, problems that in other police departments might have ended his career. In July 2019, prosecutors secured a plea agreement with him to testify against his colleagues and superiors for their role in covering up illegal actions.

John Johnson, the former chief assistant prosecutor, said his colleagues reviewed GBNET indictments that were pending at the time and decided not to prosecute many cases because of the allegations of misconduct by Cassada. William Johnson, who managed the public defender’s office at the time, confirmed that dozens of charges were dismissed. There was no record kept of those cases, he said. (None of the four Johnsons in this story are related.)

The DA’s office, however, appeared to take a more lackadaisical attitude in reviewing previous GBNET convictions, especially given the stark language used by Judge Lane in his May 28 order. There, the judge cited two constitutional violations in Whittle’s prosecution: GBNET previously knew of and hid Cassada’s misconduct because it would have invalidated his integrity as a witness. Judge Lane also declared that all five officers whom he had named in his order were impeached.

This should have put prosecutors “on notice that every single criminal defendant who was prosecuted based on the testimony of any of these listed officers — coupled with the physical evidence that was exclusively within these discredited police officers’ control — is no longer credible evidence that supports the conviction,” according to Taxel, who teaches future criminal defense attorneys at the UGA law school.

DA Jackie Johnson followed a narrow interpretation of her duty.

She wrote two brief emails, one in June and one in July, to the local bar association. The first, dated June 4, 2019, included a copy of Judge Lane’s order and a letter that said her office had compiled a list of cases potentially affected by GBNET’s misconduct. “Our office has attempted to be as inclusive as possible in identifying these particular cases,” she wrote, according to a copy of the letter reviewed by The Current.

Original versions of the emails could not be found, despite multiple public record requests. The head of Georgia’s prosecuting attorney’s council, the professional body with oversight of district attorneys, said that DA Johnson’s emails had been purged from state records after her tenure ended following her unsuccessful reelection bid in 2020.

In the first email, the DA listed 33 GBNET cases, all of which were felony drug cases where the defendants received prison sentences. In the second communication, dated July 11, 2019, she attached two additional lists that purported to show an additional 509 cases. The majority of these were drug convictions based largely on Cassada’s police work that ended in plea deals with long probationary sentences.

The lists were riddled with errors. The Current found 35 duplicate entries in which either names or case numbers or both were repeated. It is unclear whether the DA’s office was aware of these anomalies. In a number of other cases, it was difficult to determine whether the charges related to the same person, or a person with a slightly different name. The Current has identified 459 individuals but because of these inconsistencies and omissions, there may be as many as 461.

According to Johnson’s June 4 email, she then asked county defense lawyers for help in identifying further cases.

DA Johnson apparently made no attempt to disseminate these communications more widely. George Barnhill, then president of the Glynn County Bar Association, recalled the emails but could not find a copy of them. He said that they had been sent to the bar association’s general mailing list, the means typically used to alert members to court notices, vacancies, and court cancellations, or other information like pro bono workshops or federal court matters.

John Johnson told The Current that his office worked proactively with defense attorneys in the county to help correct the record of convictions, when deemed necessary. However, The Current spoke to seven defense attorneys and only one remembered prosecutors reaching out to them outside of the emails.

Other defense lawyers in the county said the emails were a cynical attempt to bury a politically charged issue and create the illusion of justice in which a superficial attempt was made to comply with Judge Lane’s order, but the people affected were never told of the opportunity for legal relief.

Approximately 85% of the cases on the list were handled by a public defender. A total of 99% of cases ended in a plea deal. In Georgia an individual who signs a plea deal also signs away all rights of appeal, thus closing their case. For those with public defenders, this ends their legal representation.

In essence, all the indigent defendants who had already been convicted no longer had a lawyer to advise them on how to get their convictions reviewed.

“That’s Brunswick…misconduct comes up, misconduct comes up, misconduct comes up…and nothing ever comes of it,” said Kevin Gough, a longtime Glynn County lawyer who has worked both as a prosecutor and a public defender.

Johnson had never indicted a single police officer during her tenure, and was not interested in re-litigating potential police misconduct, according to multiple defense attorneys.

Forgotten defendants

Like Mindy Lynn Johnson, the majority of people whose cases were included on the lists were from Glynn County and were convicted on drug charges involving marijuana, prescription medication or meth in amounts that are felonies in Georgia. And like Mindy Lynn, they had lengthy probationary sentences.

Every year for the past decade, Georgia has led the nation for adults on probation, according to data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Violations of probation, including leaving Glynn County without prior authorization, can lead to jail time. Probation revocations were responsible for 32% of prison entries in Georgia in 2022.

The gulf between how prosecutors treated GBNET defendants like Mindy Lynn, and the cops at GBNET like Cassada was wide enough to steer a cargo ship.

The woman who spurred Mindy Lynn’s arrest, CI#13, had a history of drug arrests before she began working as a confidential informant for GBNET in December 2014, according to police reports reviewed by The Current. Cassada was her primary control agent, but a review of police records showed that she worked with at least two other officers in the unit.

As an informant, she had access to networks of people like her, those who were casual or habitual drug users and had grown up in Glynn County.

Mindy Lynn knew CI#13, having both grown up in Brunswick. In January 2017, Mindy Lynn was working at a bar in Jacksonville and commuting from a modest home near the Brunswick Country Club, to support her two children.

On Jan. 4, 2017, she met CI#13 at what was then known as the Clarion Inn off I-95, in an interaction during which the informant claimed that Mindy Lynn had sold her meth. She was arrested two weeks later.

For the next several months, Mindy Lynn sat in jail waiting for her case to work its way through the court system. Meanwhile, Cassada and CI#13 engaged in behavior that violated police procedures and the law.

The informant said she and Cassada had smoked meth and had sex in his police car multiple times that year, according to a Glynn County police investigation. One of Cassada’s sources for the drugs was a man in nearby Brantley County, which is outside GBNET’s jurisdiction, according to a separate GBI investigation into Cassada.

Cassada had sexual encounters with other confidential informants as well, including one who is the sister of a fellow GBNET officer. In a later statement to police, that informant, 16-NCI-028, stated that Cassada used cocaine in her presence in 2017 and asked her to purchase narcotics for his personal use.

Another female informant stated that Cassada ordered her to participate in four separate drug buys during the summer of 2017. Cassada, however, was the only officer present for those purchases, she said, and he never officially recorded the purchases. The actions violated department policy that states all financial exchanges with informants must be documented.

A fourth female informant reported that Cassada harassed her with indecent text messages in August 2017 while drunk.

Neither Mindy Lynn nor her public defender were aware of these allegations as they tried to negotiate leniency with the prosecutors under the First Offender Act. This enables someone to avoid normal sentencing and avoid having a permanent criminal record. Mindy Lynn eventually signed a plea deal on July 7, 2017. Her sentence, like Whittle’s, was also signed by Judge Lane. It called for a 15-year sentence, three of which she served in Lee Arrendale State Prison, located 340 miles away from Brunswick, north of Athens.

Investigation yields more misconduct

While Mindy Lynn was in prison, the Whittle hearings got underway in Brunswick, and both the Glynn County police and the Georgia Bureau of Investigation had started investigating Cassada and his colleagues.

The terms of the DA’s deal with Cassada included him pleading guilty to one charge of breaking his oath of office by having sexual relationships with an informant and impeding the arrest of another. He agreed to give evidence against other officers and was never charged with drug offenses. Cassada was sentenced to spend 120-180 days in a minimum-security jail. The details of the incarceration are confidential, however, according to a spokesperson for the Georgia Department of Corrections.

Cassada received 10 years of probation. In May 2023, Superior Court Judge Anthony Harrison ended his probation six years early. Cassada’s lawyer took advantage of Georgia’s First Offender Act to expunge his record. As a result, the former police officer’s misconduct will now be absent from most standard background checks and his court record sealed.

Two of his superiors, David Haney and David Hassler, had known of Cassada’s behavior for two years and did not punish him, according to a police internal affairs investigation. They were indicted in 2020 on 10 counts including felonies such as perjury, making false statements and violating their oaths of office.

Haney and Hassler negotiated deals to plead guilty to a single misdemeanor count of obstruction of an officer. Neither man was punished beyond surrendering their police certifications. Their records were restricted as well under First Offender.

Former Police Chief John Powell and his Chief of Staff Brian Scott were also indicted for violating their oaths of office. They are fighting the charge against them, claiming they were denied their right to a speedy trial and the charges amount to policy violations, not crimes. They are awaiting a ruling from the Georgia Supreme Court.

Three other GBNET officers — Dustin Simpson, Dustin Davis and Kevin Yarborough — faced internal disciplinary actions and reprimands for policy violations like fraternizing with felons, doctoring police records, and failing to arrest one of Cassada’s informants after Cassada intervened. Simpson remains on the force, and Yarborough works for Brunswick police. As of December 2023, Davis remained employed by the county.

The Current has previously reported that between 2011 and 2019, just 10% of the more than 300 defendants where Cassada was the lead investigator received First Offender Act status.

Former DA Johnson is also awaiting trial. She is free on bond on charges related to a different, far more well-known, matter: She is accused of violating her oath of office by intervening to prevent the 2020 arrest of one of three men convicted of murdering Ahmaud Arbery, who was shot and killed as he jogged through Satilla Shores.

Mindy Lynn Johnson’s fate has been different than Johnson’s and the officers of GBNET.

In 2020, she was released early from prison on good behavior with the stipulation that she return to Brunswick to serve out the rest of her sentence on probation.

As the GBNET scandals unfolded, the possibility of legal relief never occurred to her. The CI who aided her arrest was no longer actively working for the county police. Mindy Lynn couldn’t afford a lawyer, and no one from the prosecutor’s office contacted her.

The first she heard that her case had been flagged for potential review was when The Current spoke to her in December 2023.

When first told that her case echoed a handful of other GBNET convictions that had been granted new trials due to constitutional violations, she was speechless. “You mean my case could have been one of the ones that got dropped?”

In weeks that followed, however, she stopped answering her phone. She was nervous, she said, about approaching anyone to talk about this potential avenue of legal relief because she had fallen behind on her visits with her probation officer, a blunder that she feared could land her back in prison.That may now happen. In March, Mindy Lynn was rearrested by Glynn County police for probationary violations, including driving on a lapsed license, following a traffic incident. As a result, she’s facing a return to prison.

Note: This project was completed with the support of a grant from Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights in conjunction with Arnold Ventures, as well as funding from the Data-Driven Reporting Project. The Data-Driven Reporting Project is funded by the Google News Initiative in partnership with Northwestern University | Medill School.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current.