Section Branding

Header Content

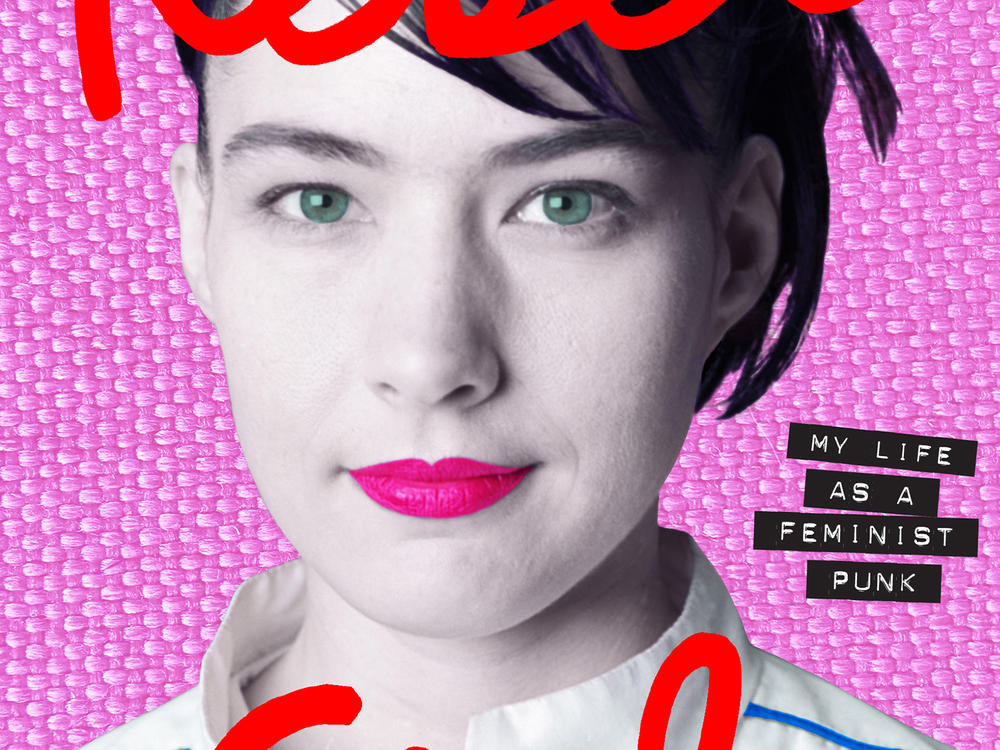

Kathleen Hanna on life as a 'Rebel Girl,' and the joy of expressing anger in public

Primary Content

Activist, musician and punk pioneer Kathleen Hanna has always been a force. With her band Bikini Kill, she pioneered the "riot grrrl" movement in the 1990s, challenging the misogyny of both the punk scene and society at large.

"When I moved to Olympia, [Wash.], there were all these kids who were making music and putting out records on small indie labels," Hanna says. "And they sort of defined punk not as a genre or a ... loud, angry, aggressive sound, but as an idea ... that we don't have to wait for corporations to tell us what is good music or art or writing. We can make it ourselves."

And so she did. Along with Tobi Vail, Billy Karren and Kathi Wilcox, Hanna formed the feminist punk band Bikini Kill. The band urged women and girls in the audience to move up to the front of the stage, write political zines and talk openly about sexual violence. Emboldened by the music, fans would come to Hanna to talk about their own experiences.

On tour, Hanna and her bandmates faced abuse and disrespect from male fans and club workers. A one point, a sound man threatened to stab her when she was touring with another one of her bands, Le Tigre.

"This was our workplace, and every single night was a different set of threatened angry men ... who would treat us with such utter disrespect," she says. "One of the things that has been getting me by is this phrase: 'In punk rock, there is no HR.' "

In her new memoir, Rebel Girl, Hanna looks back on her childhood and her experiences in the punk scene. She also writes about finding out that an undiagnosed case of Lyme disease was the reason she couldn't physically perform anymore.

Since her diagnosis and treatment, Hanna's back to to performing again with Bikini Kill and her other bands, Le Tigre and The Julie Ruin. She says there's still a lot of anger in the shows, but there's also "so much more joy."

"The songs really go from joy to sadness to rage very quickly. And I'm finding nuances in them that I didn't know were there," she says. "It feels joyous to explore our anger in public."

Interview highlights

On the early days of the riot grrrl feminist punk movement

[There were] girls in the riot grrrl meetings who were just crying because it was the first time they'd been in an all-female atmosphere, and they were just like, "Whoa, this feels really weird. I'm confused." And then like, "Wait, why have I never made this a priority before?" And just that feeling of a room changing. Just sitting at a crappy plastic Office Max table with a bunch of young women who have been relegated to the back of the room at punk shows for so long, finally saying, "I've always wanted to start a band," or "Hey, does anybody know how to play guitar? I'd like to learn." That's an amazing feeling. That really kind of changes the room into this beautiful place of possibilities.

On writing the 1993 riot grrrl anthem, "Rebel Girl"

We wrote that one in the basement of this house called The Embassy. It was a punk house, and punk houses a lot of times have names. And this one was called The Embassy because it was pretty close to Embassy Row in D.C. And I just remember how sweaty it was and it was very small. And I'll always remember writing that song because it was one of those times where I was writing it as we were playing it. So they started coming up with the music, and as it became more full-formed, I started hearing the first couple lines in my head and I just stepped to the mic, and then they just kind of fell out. I stepped back and started thinking, OK, what's the chorus going to be? ... And then I walked back to the mic and I just sang and "Rebel girl, rebel girl, you are the queen of my world" came out. And it just kind of happened. It felt like the scene of punk women that I was hanging out with, and that I was becoming friends with, really wrote that song and I just like grabbed it from the air, or something.

On how she made her concerts a safe space for women and girls

We did stuff like hand out lyric sheets that had the lyrics on them so that other girls and women would know these are the lyrics and what the subject matter was, because a lot of times you couldn't understand what I was saying through the crappy PAs I was singing through, and sometimes even talking in between songs, you couldn't understand what I was saying. And so that was one way that [we] gave them a souvenir to take home, to read through and think about and maybe disagree with so that they start their own bands or it encourages them to write their own poetry or write their own zines.

We also had zines that talked about a lot of different political issues of the day that we sold at our shows. We prioritized having girls and women come up to the front, because a lot of the shows we were playing back then, it was straight, cisgender white guys predominating and taking up all the space of the room. And we really selfishly wanted to build the community so we had more girl bands to play with. And how is that going to happen if they're all stuck in the back? ... So I started inviting the girls to the front. "Hey, do you guys want to come to the front?" And then it kind of became a thing. ... It was like, what if we just rearrange this room a little bit? What's going to happen? And what happened was a lot of men were really mad and hated us. But it was also an interesting experiment.

On a drunken night with Kurt Cobain when she graffitied a phrase that inspired the title of Nirvana's first big hit

I took out a Sharpie marker, and I just wrote like, "Kurt Smells Like Teen Spirit" because me and Tobi [Vail] had been at a grocery store and seen this new deodorant [that said] "Smells like teen spirit," and we were like, that's hilarious. What does teen spirit smell like? ... Sharpie marker and poster board? It smells like Mod Podge? What does it smell like? So we were just goofing on that. So [it] was in my head. And when I was wasted, it just came out and I wrote, like, 10 other things on his wall — and he was a renter, so that was kind of a bad move on my part. Not very kind or thoughtful. And then he called me on the phone many, many months later and was like, "Can I use that in a song?" I didn't even know it was going to be the title for a song. And I was like, "Yeah, sure, that's great."

Thea Chaloner and Joel Wolfram produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Meghan Sullivan adapted it for the web.