Section Branding

Header Content

Yamacraw residents wait as Savannah housing area continues to deteriorate

Primary Content

Julian Gentin, The Current

In June 2020, the Housing Authority of Savannah announced its decision to demolish Yamacraw Village, a decrepit public housing development in downtown Savannah’s oldest Black neighborhood.

Four years later, Yamacraw, by most estimates, is in more disrepair, less safe and has fewer residents. The estimated 130 tenants who remain still are unsure of what their futures hold.

That’s because the housing authority is waiting for the City of Savannah to complete its portion of a vital federal form necessary to move the demolition plans forward. And the city has displayed little urgency in finishing the document.

Meanwhile, life for residents has deteriorated. In June, the housing authority started eviction proceedings for at least 11 Yamacraw tenants, according to Chatham County Magistrate Court records.

On Monday, federal officials from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) — which is in charge of approving the demolition application — will visit Yamacraw.

Ahead of the visit, several residents who still call the two-story buildings home told The Current they had no idea about how decisions are being made that will impact their futures. Some say the present circumstances are intolerable.

Resident conditions

Malikah Collier has lived in Yamacraw for 3 1/2 years with her daughter. Her water pipe is broken — the unit has flooded twice — and the air conditioning is not reliable, she says. When Collier moved in her rent was $300 per month, but it’s now $750, an increase due to her better paying job.

But the deteriorating conditions of her home, the lack of responsiveness to fix what’s wrong and the struggle to make ends meet are the reasons she says she’s looking for a new place outside of Savannah.

“It takes forever to fix things. They drag their feet,” said Collier, a Savannah native who works at a day care. “I’m taking it one day at a time. Hopefully they let us know something (about the demolition) if I don’t move before then.”

Timeline for demolition

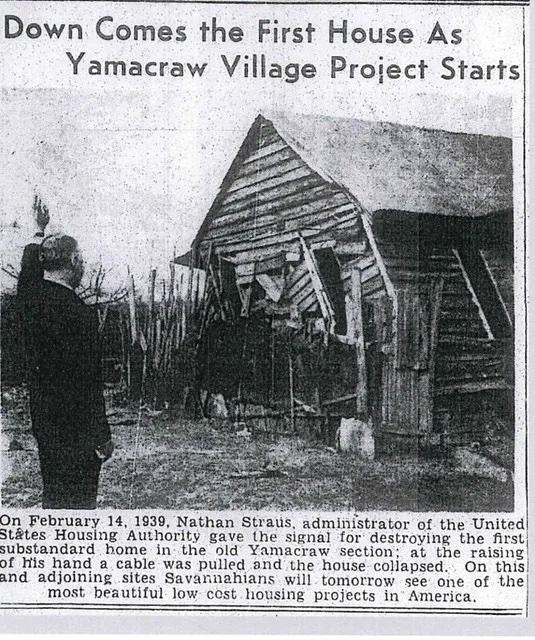

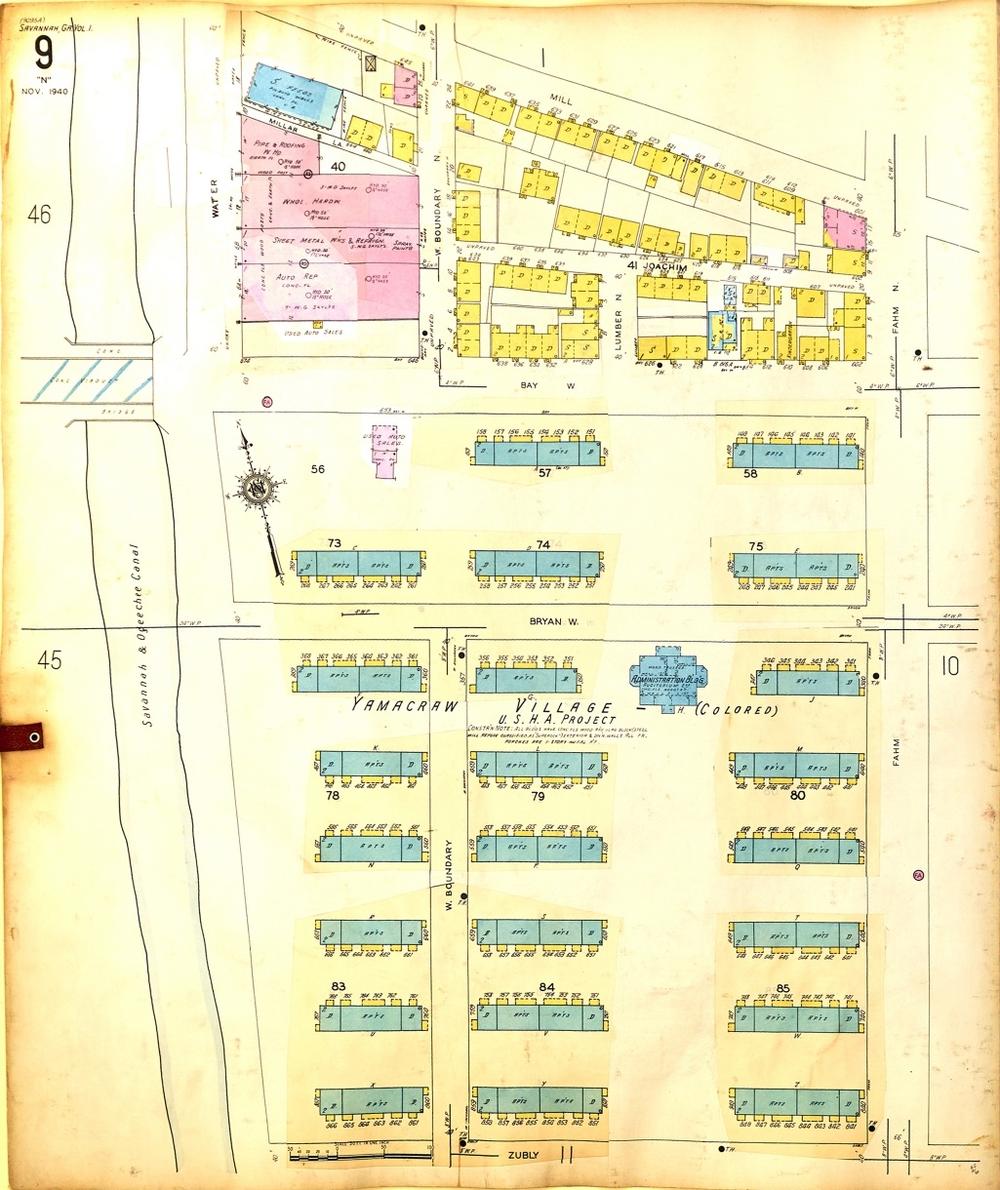

In the early 20th century, Yamacraw Village was a vibrant African-American community, the subject of songs and poetry. Then it became ground zero for federal policies known as slum clearances, and 3,000 residents were displaced.

The public housing community that was built in the 1940s was once seen as a benefit, but that changed years ago. Yamacraw Village is again known as a slum-like development.

A 2019 Capital Needs Assessment found that living conditions had deteriorated to the point that Yamacraw would need $40 million of capital improvements for repairs. A 2023 report raised the cost of renovation to $51 million.

In June 2020, the housing authority adopted the motion to demolish Yamacraw Village, according to their Public Housing Repositioning Plan, saying that it would be more cost effective to rebuild than to renovate the sprawling complex.

The housing authority submitted in 2021 federal documents necessary to start the demolition, but HUD kicked it back in 2022, objecting to parts of the environmental assessment.

The housing authority gave itself a deadline to resubmit by September 2023.

The current demolition application, which is approximately 2,000 pages long, is “90% complete,” said the housing authority’s Director of Asset Management Rafaella Nutini, but at least one significant section is not finished.

City officials, not her department, are responsible for that section, she said.

“I don’t want to get into trouble about putting the date out there, but we would love to have this environmental review process done in the next few months. We’re anxious to move forward,” said Deputy Director of the housing authority Kenneth Clark.

Joshua Peacock, the city spokesperson, told The Current that the city hopes to have the Section 106 Review “completed this year.” A contracted historic preservation professional is conducting the last step of writing a full report on the findings, he said.

Nutini said the last time she spoke with someone from the city was around two months ago.

Residents without a voice

One of HUD’s main criticisms in the first demolition application was that Savannah failed to have adequate consultation with interested parties — Yamacraw residents, community groups, and Digging Savannah, an archaeological project.

Because Yamacraw is a federally funded development, what’s known as a Section 106 review is required to evaluate the demolition’s effects on the historic properties. HUD also requested more information about environmental consequences. That includes effects on residents.

In the previous four years, the city and housing authority say they have sought to engage residents in the planning process for the future.

Yamacraw residents do have representatives on the public housing advisory board, but there is not a Yamacraw-specific homeowner’s association or resident council.

“There’s no voice for the residents,” said Bob Spell, co-founder of the Yamacraw Restoration Project.

The city has distributed a survey for a part of the historic review. It has held two in-person meetings with Yamacraw residents and the local community, Peacock said.

Those meetings, however, were held during the day, making it difficult for Yamacraw residents who work to attend.

“They weren’t as accommodating as they should’ve been,” said Ellie Isaacs, who worked on preservation efforts for First Bryan Baptist Church, the oldest standing church in Savannah that’s located in Yamacraw Village.

The delays are meant to help residents of Yamacraw, in theory. In practice, advocates like Dr. Amir-Jamal Toure’, a scholar of Black history in the area, believe that they marginalize some of Savannah’s poorest families.

History, he says, is repeating itself because of the rush of displacement among tenants.

Yamacraw was at 43% occupancy as of April 30. If the 11 June eviction notices are completed, the occupancy rate would drop to approximately 39%.

Being displaced again means that “the people don’t know who they are. They are like a leaf in the wind: wherever the wind blows, that’s where they go,” Toure said.

“The occupancy is so low,” Spell said. “It’s almost like (the housing authority) is waiting for people to move out, so that they say: ‘Oh, we only have 20 families we need to accommodate in the new development’.”

In HAS’ five-year plan for 2024-2028, which is subject to change, there are funds allocated to the improvement of common areas, like the Curtis V. Cooper Primary Health Care building, which will not be torn down.

But there’s no money going to the dwelling rental units, because those are set to be demolished, Nutini said.

Collier, the daycare worker who has lived in Yamacraw since September 2020, said some residents feel like they don’t need to pay rent because the housing authority “isn’t doing what they should to keep us comfortable.”

An uncertain future

With the timeline of demolition still unknown, advocates for Yamacraw are concerned about another urgent issue. Where will Yamacraw residents go — and will they be able to return to the neighborhood?

The demolition application that the housing authority is pursuing means Savannah is not required to replace the 315 units of public housing that are currently at the Yamacraw complex.

“There’s no legal requirements but the housing authority’s mission is to provide affordable housing,” Nutini said. “We would love to listen to the community and residents and provide a sound, comprehensive, revitalization plan for that site…we could probably double the amount of units in Yamacraw if we wanted to.”

Those discussions, however, are on hold until HUD approves the demolition application and the housing authority’s subsequent decision about a developer, Nutini said.

In the meantime, current residents are doing their best to make the best of the situation.

Yamacraw resident Katie Divine and her across-the-street neighbor say they are grateful for their current living conditions.

Divine’s home is located next to two boarded-up units. She sits on her front porch and watches the neighborhood hollowing out. Her mother grew up in Midway, her father hailed from South Carolina’s Low Country. She talks about the people buried here centuries ago and hopes to be rehoused in Yamacraw, her longtime home, following the demolition and redevelopment.

Divine says she finds moments to celebrate amidst the uncertainty — she’s buying a cake and decorations for her 79th birthday next week.

“Everybody is moving out,” Divine said. “You don’t hear shootings anymore because there’s no one here.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current.