Caption

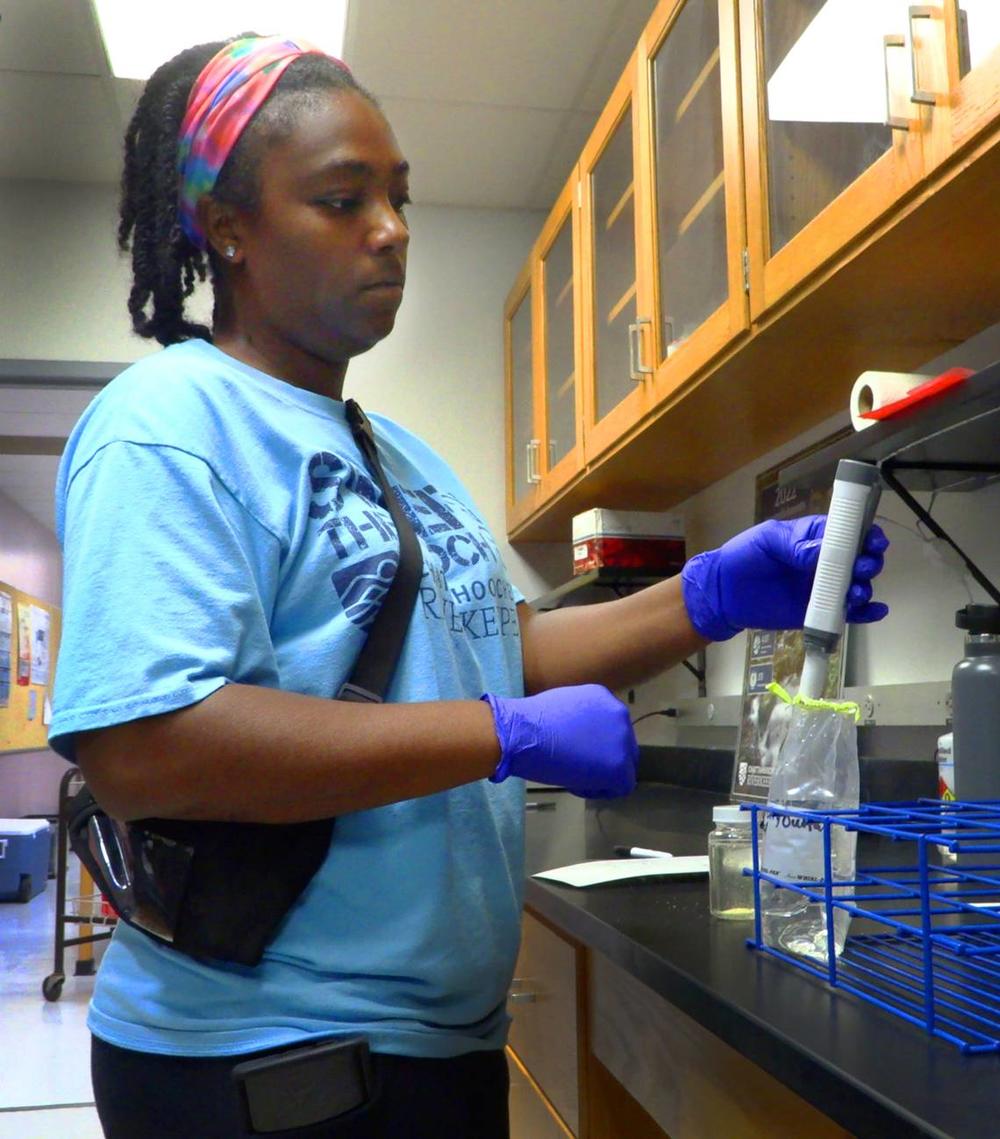

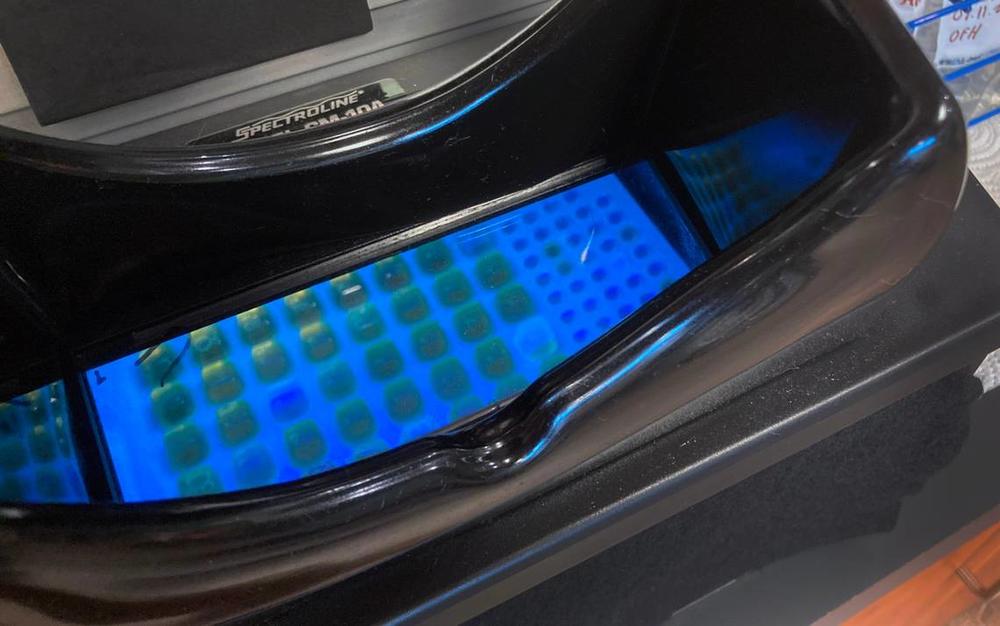

The Chattahoochee Riverkeepers serve as watchdogs for water quality in the Chattahoochee River, including the Columbus stretch of the waterway. See their process, and why they're concerned about the water quality in some areas.

Credit: Mike Haskey/Ledger-Enquirer