Section Branding

Header Content

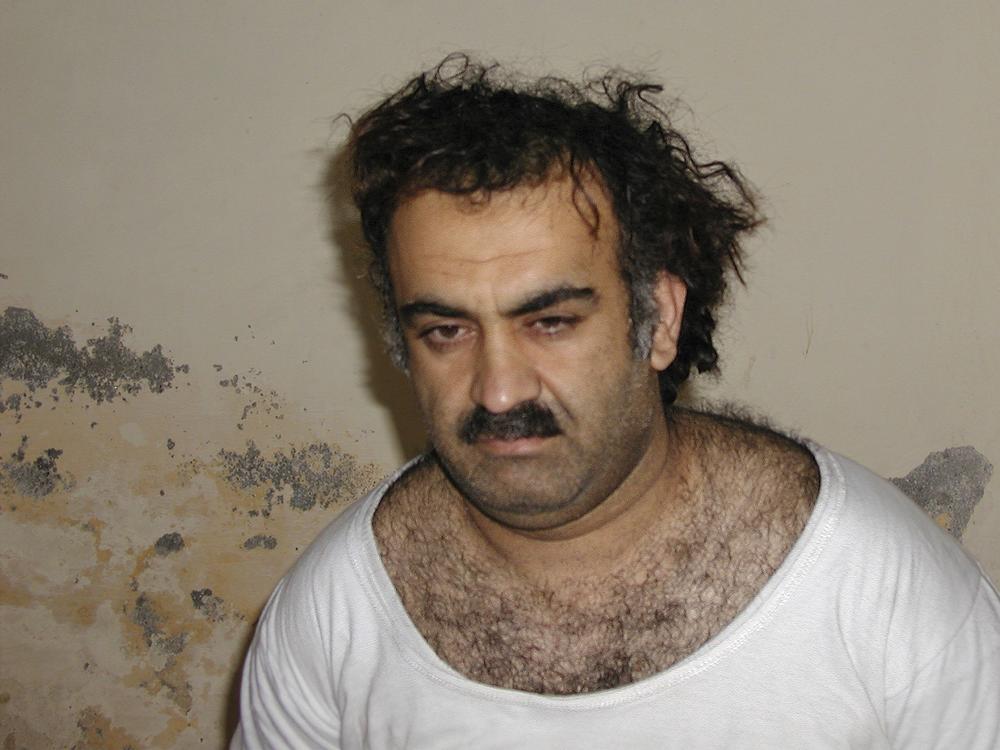

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, accused as the main plotter of 9/11, agrees to plead guilty

Primary Content

After spending almost two decades in the U.S. military prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, the alleged mastermind of the 9/11 terror attacks, Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, and two of his accomplices have agreed to plead guilty in exchange for sentences of up to life in prison rather than face a death-penalty trial.

The settlement agreements with the Pentagon, announced Wednesday, bring partial closure to a case that has dragged on for twenty years and become mired in legal gridlock. Many family members of the nearly 3,000 people who died in the September 11, 2001, attacks want the 9/11 defendants put to death, but as a trial became increasingly unlikely, plea bargains were widely viewed as the only way to resolve the case.

This week's settlement agreements are an acknowledgement of that reality by the U.S. Defense Department. In a letter to victim family members, Guantánamo prosecutors wrote that the decision to settle "was not reached lightly; however, it is our collective, reasoned, and good-faith judgment that this resolution is the best path to finality and justice in this case."

Mohammed and two of his co-defendants, Walid bin Attash and Mustafa al-Hawsawi, are accused of plotting the 9/11 attacks, and as part of the settlement they will plead guilty to conspiracy and murder charges. They are expected to receive life in prison.

Settlement talks had been underway for more than two years, but appeared to have stalled after the Biden administration rejected some proposed conditions, including a request by defense attorneys that the defendants not be put in solitary confinement. The defendants, who were tortured in secret CIA prisons called black sites, also requested medical care for their lingering injuries.

Their past torture is largely responsible for bogging down the case, since prosecutors and defense attorneys have been arguing for years over whether evidence obtained through torture is admissible in court. In a recent ruling that did not bode well for 9/11 prosecutors, a judge in another different Guantánamo case -- the U.S.S. Cole warship bombing -- threw out a confession because he said it was a product of torture.

That legal development may have played a role in the U.S. government deciding to settle the 9/11 case.

In a statement, the National Security Council said that "the President and the White House played no role in this process" and learned of the plea bargains on Wednesday.

It is not yet clear where Mohammed, bin Attash and al-Hawsawi will serve their sentences. An American law currently prevents them from entering the U.S. for any reason, including to go to a supermax, so they could remain imprisoned at Guantánamo until their deaths.

In an interview with NPR, Terry Rockefeller, whose only sibling -- her younger sister, Laura -- died at age 41 in the World Trade Center attacks, called the plea deals "the beginning of the end of an incredibly long journey."

Rockefeller noted that settlement agreements cannot be appealed, "and, to me, that is judicial finality, and that is worth a lot." She added that she is "deeply sorry about the number of victim family members who didn't live to see this day."

Another victim family member, Brett Eagleson, who was 15 when his father died in the World Trade Center collapse, sent NPR a statement issued by a group called 9/11 Justice that said it was "deeply troubled by these plea deals," calling them the product of "closed-door agreements where crucial information is hidden without giving the families of the victims the chance to learn the full truth." In particular, 9/11 Justice is focused on Saudi Arabia's role in the attacks.

One aspect of the settlement is intended to address those concerns: As part of their plea bargains, the 9/11 defendants will be required to answer questions by victim family members about how and why they planned the attacks.

Guantánamo prosecutors said the defendants could formally plead guilty as early as next week. But the case will continue for at least another year; the defendants will be sentenced at a separate hearing that will not occur before September 2025, according to the prosecution's letter to victim family members.

There are two remaining 9/11 defendants whose cases must still be resolved. One is Ramzi bin al-Shibh, who last year was declared mentally incompetent to stand trial. The other is Ammar al-Baluchi, who has not settled primarily because he wants any plea bargain to include post-torture medical care, according to one of his lawyers, Alka Pradhan.

Still, Scott Roehm, director of global policy and advocacy at the Center for Victims of Torture, called the plea agreements "an enormously important achievement, a critical step towards closing Guantánamo, the only path left to any measure of justice and finality for 9/11 victim family members, and the only way, more broadly, to end the sad saga of the military commissions."