Section Branding

Header Content

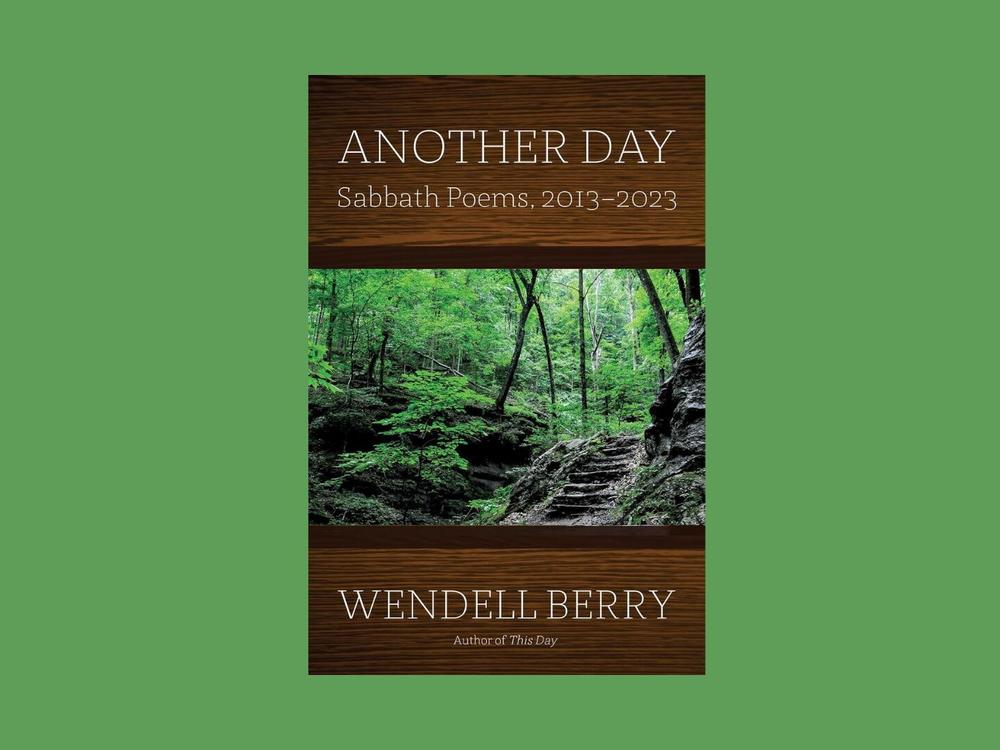

Wendell Berry veers from gratitude to yearning in 'Another Day'

Primary Content

Wendell Berry’s imagined residents of Port William, Kentucky, are nearly as familiar to his most devoted readers as their own extended family members.

In a series of novels and dozens of short stories -- populated by recurring characters set over decades -- Berry brings alive the joys and sorrows of hard-working rural Kentuckians. His writing is informed by his own long-time farming life in a Kentucky River valley, one shared with Tanya Berry since their marriage in 1957.

Berry’s talents span genres. His essays offer firebrand non-fiction that takes on the destructive forces that kill off traditional ways of farming. In both his novels and essays, there’s an ever-present tenderness for the land, for human community, and for nature, mixed together with a blazing anger at the machine-driven forces that threaten them and our environment.

In a new collection of poetry Another Day: Sabbath Poems, 2013-2023 -- a sequel to This Day: Collected & New Sabbath Poems that spans the years 1979-2012 -- Berry’s themes are revisited in ways both familiar and fresh. There’s a veering from gratitude to yearning in Another Day, an oscillation heightened perhaps by the profoundly reflective thinking of a writer in his 80s; Berry celebrated his 90th birthday Aug. 5.

Berry conveys so perfectly the overlapping emotions of love and grief that, at times, I read through tears (this from 2013, poem IV):

What comes is the light, dim,

almost substantial, of the oil lamp

in the middle of the kitchen table,

casting into the dark around it

the shadows of the old grandparents

and their small grandson at supper.

The poem ends this way:

Now, their equal finally

in years, how he loves them, how

he misses them. How carefully still

he holds them in his thanks.

There’s enduring love for Tanya in these poems. he refers to her in "2022, poem I, dated 5/29/22," saying love "came to him one time in the person of a girl/ and it abides in the girl’s great-grandmotherhood."

Reverence for God is here too; after all, these are sabbath poems (Berry does not always capitalize the word.) In the introduction to the earlier volume This Day, Berry writes about the notion of the sabbath as a day of rest, qualifying it as a day when people might understand that “the providence or the productivity of the living world, the most essential work, continues while we rest.”

In Another Day, the reverence is sometimes made explicit (2015, poem XIII):

It is only the Christ-life,

the life undying, given,

received, again given,

that completes our work.

More inviting, I think, are praise poems that keep open an interpretation that can be religious, or not. In one poem, there’s a sheep who gives birth and bleats out "her absolute eloquence of joy." In another, the trees' company offers "the luxury of wordlessness." And in yet another, there are phoebes that "dance/ in the air, on the branch,/ their love for one another."

Indeed, Berry asks us to see, truly see, other lives -- and when we cannot, to know nonetheless they are there, vitally helping to make our world (2014, poem VIII):

To care for what we know requires

care for what we don’t, the world’s lives

dark in the soil, dark in the dark.

A delicious sharpness marks Berry’s writing about screen obsession -- our cultural commitment to staring at, playing with, and living through computers and phones that diverts our seeing what (and who) matters (2013, poem XVII):

Looking at screens,

listening to voices

in nonexistent distance,

seeing, hearing nothing

present, we pass into

the age of disembodiment

For the industrial machines that rend the Earth, that scale up in size and economy the destruction of small farms and the environment entire — Berry reserves a special seething. A long poem from 2023 most fully tells this story. In it, a man dreams that he returns from the dead to a country he knew, his own place in life (2023, poem I):

But now iron and fire had passed

over it, and everything was gone:

everything above the ground,

every building, every tree,

every stone that marked our graves.

What follows is a dialogue with a “familiar voice” in which the dreamer’s “participation in the conflagration of the world” is interrogated, as is much else; the dreamer asks why he was brought to that place. The reply comes as the poem’s conclusion:

Your dream of the ruin of your home land

now brings alive in you your small

share of the greater love that made

the heaven and the earth. Highest

and whole, that love is the Sabbath morning

where you at last may come to rest.

Like Berry’s fierce essays and luminous novels, these poems offer gifts of vision, of knowing that there is another way to live now on this Earth: a way that honors love, the land, and all beings. Can any of us rest while there's still a chance to bring that about?