Section Branding

Header Content

Deluxe: The Ones Who Were Here Before Us - Uncovering America's Indian Boarding School Program

Primary Content

In this episode of Salvation South Deluxe: Chuck Reece details the United States's brutal program of forcibly assimilating Native American children through boarding schools in the late 19th and early 20th century. He learns the historical context of this act of warfare; the lasting trauma it created; and the Native-led efforts to heal its generational wounds.

TRANSCRIPT:

PART ONE:

Chuck Reece: How to explain Southern culture?

For over a decade, I’ve edited publications like Salvation South that have tried to explain it. I generally rely on this handy metaphor:

It’s like a pot of gumbo. Gumbo is the official state “cuisine” of Louisiana, and it’s a stew that’s been around for well over two-hundred years. It’s a great metaphor for the South because it possesses the influences and ingredients of the African and Caribbean people who were brought here as slaves and the European colonists who enslaved them. And okra, a plant Native to Africa whose seeds arrived here in the pockets of the enslaved, is what binds the whole thing together.

Chuck Reece: A pot of gumbo is a glorious harmony of flavors and textures and beauty, emerging from the worst kind of ugliness.

I’ve been milking that metaphor for all it’s worth for a long time.

But today I have to admit — out here in public, in front of all of you — that I haven’t been speaking the whole truth. It’s not that I was lying. But I was leaving something out — something important.

You ever hear Hank Williams sing this line?

MUSIC: Hank Williams - "Jambalaya (On The Bayou"

Jambalaya, crawfish pie, filé gumbo…

Chuck Reece: Filé gumbo. Another ingredient that went into the Southern gumbo pot centuries ago was filé powder. Filé is the dried leaves of a sassafras plant. It helps the okra to thicken your gumbo, and it takes the flavor up into the gastronomical stratosphere.

Filé wasn’t a European thing. Nor was it an African or a Caribbean thing. It was an Indigenous Peoples thing, a Native American thing, specifically a Choctaw Nation thing.

So, while I waxed on endlessly regarding what gumbo says about the South, I’ve been leaving out the ingredient that was put in the pot by the people who lived on this land before us — before either the enslaved or the enslavers got here.

The fact we so often neglect to incorporate Native people into our stories of American culture is … well … it’s basically a dreadful, selfish crime.

The magnitude of my omissions came home to me in a big way about a year ago. I was interviewing my friend Malinda Maynor Lowery. Malinda belongs to the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. I first met her when she was the director of the Center for the Study of the American South at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. A few years ago, she moved to Georgia to become the Cahoon Family Professor of American History at Emory University.

I was working on a story about the roots of Southern music. I knew how the blues arose from the laments of the enslaved. I knew how the blues met the brass and woodwind instruments of European classical music to create jazz. I know how country music’s roots extended back to folk tunes from the British Isles.

But I did not know much about how Native American culture factored into the music of the South. So I called Malinda. And she promptly took me to school. She told me that if I wanted to understand how the culture of Indigenous Peoples fed into the culture of the South, I needed to extend my view back beyond the colonial period. Instead of thinking four hundred years into the past, she said, I should try a bigger number. A far bigger number. Like, say, twenty-thousand.

Malinda Lowery (from 2022 interview): It's he thousands of years of cultural development that took place leading up to 1492. And because there were not Europeans here to write down what they heard, I think sometimes historians or even more casual observers get lost in that, like, if-a-tree-fell-in-the-forest question. It's like, "Okay, yes, the tree makes a sound scientifically.”

It must make a sound. … It doesn't require white people to note that something is happening in order for us to understand that music was here, culture was here, and every way, shape and form of people creating something, creativity was here.

Chuck Reece: I come from a generation of public-school Southerners who were taught precious little about our ancestors’ treatment of the African and Caribbean people they kidnapped and brought here.

I had to learn for myself they didn’t even see their slaves from Africa and the Caribbean as human. They saw them, really, as livestock. You could buy them and sell them, like cattle.

Even after I learned that history, sadly, it did not occur to me to ask the parallel question: how did our European ancestors view the Native peoples who were already here?

Today, we’re going to ask that very question. And we’re going to learn some things — things that will chill you to the bone.

Chuck Reece: I’m Chuck Reece, and welcome to Salvation South Deluxe, a series of in-depth pieces that we add to our regular podcast feed. We try to unravel the untold stories of the Southern experience by letting you hear the authentic voices that make this region truly unique.

THEME MUSIC UP

Chuck Reece: When I went back to Dr. Lowery at Emory to talk to her for this episode, I figured I should go straight to that big question, right from the beginning: how did our European ancestors see the Indigenous Peoples who were here when they arrived, and why was I not taught about that when I was young?

Malinda Lowery: It's a story as old as the nation itself, why you didn't know. … In some ways it goes back to that ‘merciless Indian savages’ little comment in the Declaration of Independence.

Chuck Reece: Wait? What? I thought I learned the Declaration pretty thoroughly from the “Schoolhouse Rock” cartoons.

MUSIC: Schoolhouse Rock - "Fireworks (Declaration of Independence)"

We hold these truths to be self-evident. That all men are created equal. That they are endowed by their creator...

Chuck Reece: After Thomas Jefferson declares all men are created equal, he continues writing and airs his grievances with King George the Third.

The History of the present King of Great-Britain is a history of repeated Injuries and Usurpations, all having in direct Object the Establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid World.

He then lists twenty-eight specific grievances. The twenty-seventh of those reads:

The King has excited domestic Insurrections amongst us, and has endeavored to bring on the Inhabitants of our Frontiers the merciless Indian Savages.

That’s right. Our Declaration of Independence says all men are created equal. Then, about nine-hundred words later, the declaration says the Indians … well … they're not people.

Malinda Lowery: The existence of the entire idea is bound up in racial supremacy and cultural supremacy, religious supremacy, gender supremacy, you know, class supremacy, like all kinds of things.

The whole idea of writing off, paving over Native people's experiences is, like, kind of a founding principle of the United States.

Chuck Reece: Dr. Trey Adcock is an enrolled member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, and he’s an associate professor of Interdisciplinary Studies at the University of North Carolina-Asheville. He is also the Director of Indian & Indigenous Studies there.

Trey Adcock: The history and the legacy of colonization for American Indian people in the United States, I mean, it's really got three heads. It's military conquest, it's conversion through the churches. And then, forced assimilation through the schools.

Chuck Reece: Given Jefferson’s conclusion the Natives were “merciless savages,” it makes sense the colonists’ agenda included military conquest.

British colonists settled the first colony, Virginia, in sixteen-oh-seven. By sixteen-ten, they were already at war with the Powhatan people, the tribe on whose land they established their first city, Jamestown.

Malinda Lowery: I would also kind of add like a fourth hydra head. Of economic dispossession.

You know. Mass killing of bison. Ruining ecologies so that salmon cannot run. Burning grasslands. I mean, in the case of my folks in eastern North Carolina. Destroying the longleaf pine tree so turpentine can be extracted and ships can be built in Europe and you know. That type of. It's a, it's a little, sometimes a little slower, that sort of economic, dispossession. But it leads to the loss of land and leads to loss of control over our political, our governments. You know, our ability to make decisions for ourselves.

Chuck Reece: The day after I spoke to Dr. Lowery, I was reading a travel story in The Washington Post about a writer’s railroad journey from Northern California to New York, when I happened upon this passage:

And I quote:

Our conductor, when providing a brief history of rail travel, recounted a railroad operator who would pause the train when it encountered a bison herd, encouraging passengers to disembark to shoot the animals (‘kill the buffalo, kill the Indian’ as the mantra went).

In eighteen-nineteen, the U.S. Congress passed legislation establishing the Civilization Fund. Our modern mind might hear those two words and think, “Oh, a fund for the betterment of our civilization. Nice!” But that appropriation was meant to fund any program that “civilized” the “savages.” It was for the purpose of — and I quote — ”introducing among them the habits and arts of civilization.”

Here’s Trey Adcock again.

Trey Adcock: This notion that, you know, Native people were savages and uneducated, blah, blah, blah, blah. I mean, it's just absolutely garbage.

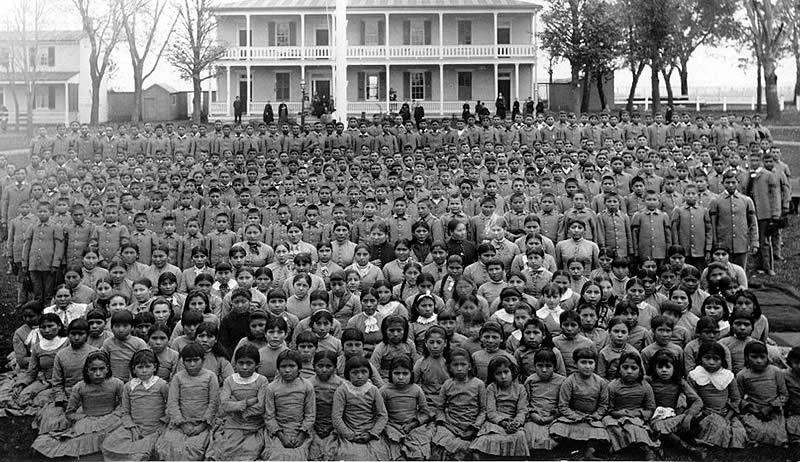

Chuck Reece: Eleven years later, President Andrew Jackson signed into law the Indian Removal Act, which dictated the forced march of all Native people east of the Mississippi River all the way to Oklahoma. That was over sixty-thousand people from eighteen tribes, which included the five major tribes — the Cherokee, the Muskogee, the Choctaw, the Seminoles, and the Chickasaw.

The governments of all those tribes are now located in Oklahoma. The Eastern Band of the Cherokee, of which Dr. Adcock is a member, is headquartered in Cherokee, North Carolina. The approximately fourteen-thousand members of the Eastern Band descend from the eight-hundred to one-thousand Cherokees who avoided the forced march. By hiding in the Appalachian Mountains or other means.

Dive into the history of the U.S. Government’s relationship to Native Peoples, and you will find no evidence of a desire to live with the American Indians. The goal was to eliminate them. Our history is filled with armed conflicts between the U.S. Military and the Native tribes. The decades after the Indian Removal Act saw the Black Hawk War. Then nthe Seminole War here in the South. Then the Black Hills War in South Dakota - that one included the famous Battle of Little Big Horn, where General George Custer met his end. Eighteen-ninety brought the Massacre at Wounded Knee, where the U.S. Army killed over three-hundred Lakota Sioux people.

As we moved closer to the turn of the twentieth century, the U.S. government expressed a desire to move from military conquest to assimilation. But assimilation through cooperation was not their model. It was assimilation by force.

I’ll explain their methodology to you by asking you, dear listeners, a hypothetical question:

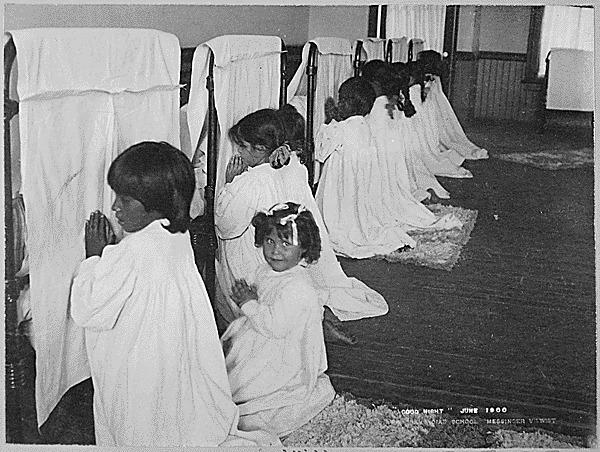

How would you react if federal officers came to your house and took away your children? Then moved them hundreds of miles away to a boarding schools? And what if they took away your children’s names and gave them new ones? And what if, anytime your kids spoke the names you gave them, or even a word of your Native language of English, they would be beaten?

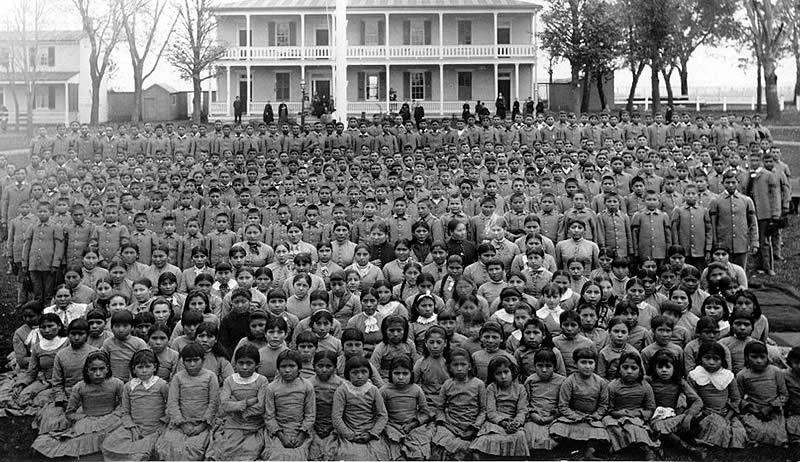

Didn’t think you would like that. But that is exactly how the U.S. government treated thousands of Native families. This practice went on for well over a hundred years. It did not end until nineteen-sixty-nine.

Salvation South Deluxe will be back after this short break, and we’ll share some stories that shed light on the history of federal Indian boarding schools.

PART TWO:

Chuck Reece: To understand the U.S. Government’s attempt to use boarding schools to assimilate Native children, you need to meet a U.S. Army brigadier general named Richard Henry Pratt. General Pratt fought on the winning side of the Civil War and then in the Indian Wars on the Great Plains through the mid-eighteen-seventies.

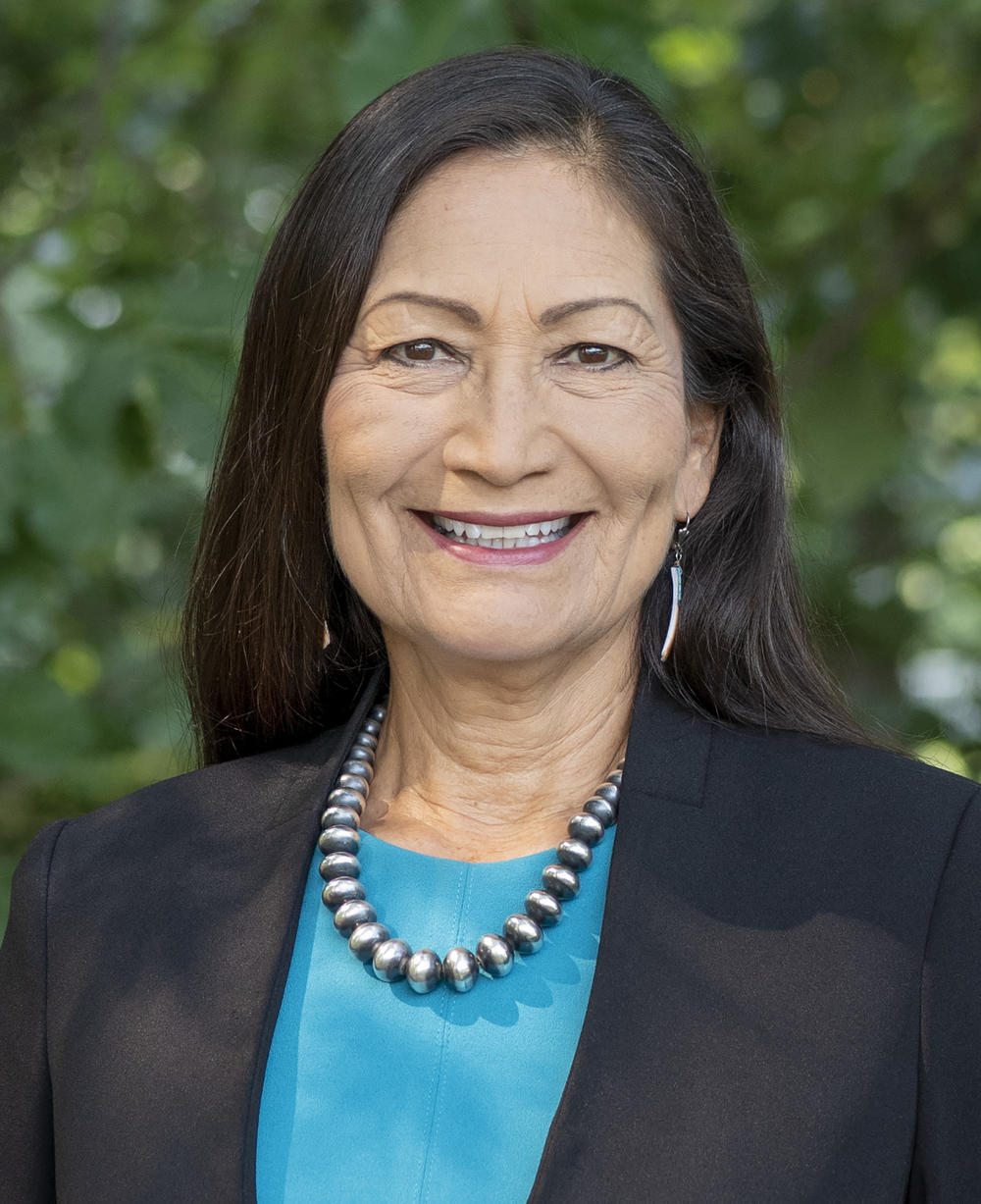

In eighteen-seventy-nine, Pratt founded one of the largest federal boarding schools for Native children. The Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He fancied himself a reformer, one who wanted to leave behind warring with the Native Peoples in favor of “Americanizing” them. According to Pratt, that meant Native people needed to leave the reservations, renounce their historical ways of life and faith, and convert to Christianity.

In eighteen-ninety-two, Pratt was invited to speak at the National Conference of Charities and Correction in Boston. The title of his presentation was “The Advantages of Mingling Indians With White.” Yes, Pratt was for mingling, but only after Natives had been assimilated completely into the ways of white people. Pratt’s speech contained a phrase that so perfectly captured the purpose of the federal Indian boarding schools, it is still used today. Let me read you the paragraph that ends with that phrase:

A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one… In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.

Kill the Indian in him and save the man.

Here’s Trey Adcock again:

Trey Adcock: Richard Pratt, you know, was really kind of the architect of the boarding schools. And you know, the legacy of that lives with us. Carlyle was sort of the blueprint. But the boarding school spread pretty rapidly. And, you know, they removed kids from their homes, they shipped them thousands of miles away. I think what you've heard in the news recently, both here and up in Canada, is, you know, lots of kids died in these schools. The conditions were deplorable. You know, it was forced assimilation. So they were, you know, stripped of their names. They were, you know, beaten for speaking their languages. You know, cultural practices were forbidden.

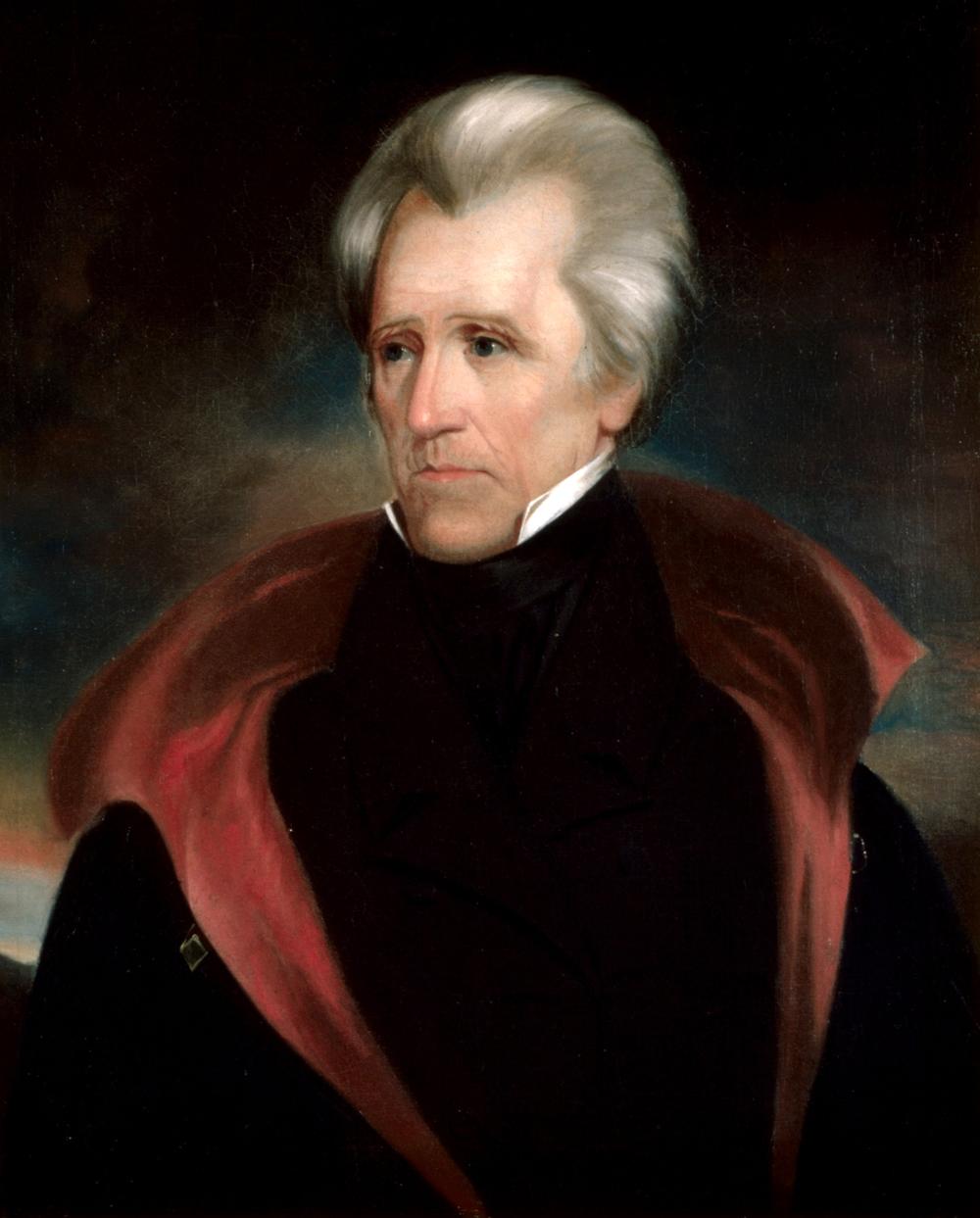

Chuck Reece: The history of the boarding schools has, as Dr. Adcock says, made the news lately, thanks to the efforts of the United States Department of the Interior. When Joseph R. Biden became president in twenty-twenty, he appointed Deb Haaland as secretary of the interior. She is the first Native American ever appointed to a cabinet post.

I found it enlightening to read Secretary Haaland’s short biography on the Interior Departments’s website.

You know, over the years, I’ve talked to many people who have worked hard to document their family trees. If you hear someone say their family has been here for ten generations, that usually means the family arrived on this continent in the early seventeen-hundreds or late sixteen-hundreds, decades before the United States became a nation.

When you read Deb Haaland’s bio, it begins this way:

Secretary Deb Haaland made history when she became the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary. She is a member of the Pueblo of Laguna and a 35th generation New Mexican.

The Senate confirmed Haaland’s appointment in March of twenty-twenty-one, and three months later, she launched an investigation into the history of Indian boarding schools.

This is Secretary Haaland, speaking in an Interior Department video press release.

Secretary Deb Haaland: One of the reasons I launched the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative was to ensure that this important story was told—that all of America knows of the intergenerational impact of these policies and that we as a nation take steps to heal from them.

Chuck Reece: Not long ago, the Indian Boarding School Initiative released the final volume of its two-hundred-and-eleven-page report.

A quick summary of the findings?

Ultimately, there were more than four-hundred boarding schools spread across thirty-seven states or then-territories, including Alaska and Hawaii. Tens of thousands of Indian children in those schools were given English names and were prevented from using their Native languages, or continuing the religious and cultural practices they had been raised with. Those who violated the rules were punished by whipping, flogging, solitary confinement, and the withholding of food. Almost a thousand children died while in the schools, and the documentation efforts are still going. Fifty-three marked and unmarked burial sites have been documented on boarding school grounds.

Dakota Brown: My great-great-grandfather on my grandmother's side of the family was the first person to go into boarding school. He went to Carlisle Boarding school in Pennsylvania. Which was the original boarding school.

Chuck Reece: That is Dakota Brown.

She is a citizen of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and the director of education for the Museum of the Cherokee People in North Carolina.

Dakota actually studied Native history under Trey Adcock at the University of North Carolina-Asheville several years ago. Her senior thesis focused on how the Cherokee language began falling out of use. In her research, she found a direct correlation between language loss and the time when a Native child entered a boarding school run by the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Dakota Brown: Ultimately, what my thesis centered around is how BIA education had adverse effects on community in multiple ways, but especially the language. The BIA education systems can be directly tied to the language loss that we're still facing today.

You can look back in your family, you can trace the first person that goes to boarding school in that family line is also where the language stops.

In my research, I think I called it a language line in a family, where you can see the person in a family. So like in my family tree, for instance … If I look at my grandmother’s side of the family … the generation that stopped speaking the language was the generation that entered Bureau of Indian Affairs School. They went to boarding school.

Chuck Reece: But on her grandfather’s side of her family, Dakota is only two generations removed from being a Native Cherokee speaker. That’s because her grandfather’s family was part of a tiny, isolated community about an hour west of Cherokee, North Carolina, called Snowbird.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs did have a school in Snowbird, but it wasn’t a boarding school. The Cherokee kids who attended it went home after school every day.

Dakota Brown: My grandfather was the first person in his family to go into the BIA education system. He went to the Snowbird Day School, and he didn't learn how to speak English until he was, like, thirteen.

Chuck Reece: Day schools like Snowbird were the product of the Franklin Delano Roosevelt administration in the nineteen-thirties.

Here’s Trey Adcock again.

Trey Adcock: Most people know FDR and know the economic New Deal, the Great Depression. Less people know about the Indian New Deal. John Collier was appointed.

Chuck Reece: John Collier, a Southerner born in Atlanta, was a sociologist who, in the early nineteen-twenties, went to New Mexico to study the Pueblo tribes. By the time he left New Mexico, he opposed the government’s assimilation policies. When Franklin Roosevelt became president in ninteen-thirty-three, he appointed Collier to be his commissioner of Indian Affairs.

Trey Adcock: He had spent time out west, particularly, on Native reservations. Was reform minded. And that's really what he brought in the Indian New Deal. … Part of that was phasing out the boarding schools, the big boarding schools, creating more day schools. You know, and he has a very mixed legacy. It depends on which part of the Indian country, you talked to. Right. But, I mean, you know, in a lot of ways, he was attempting to do better.

Chuck Reece: The Snowbird Day School remained open until the nineteen-sixties, when the federal courts required racial integration in the public schools of the South. That court directive sent the Cherokee children of the Snowbird community into the local school system.

In twenty-seventeen, Dr. Adcock and his then-student Dakota Brown began an oral history project to document the stories of Cherokees who attended the Snowbird Day School. As they interviewed the alumni, they heard stories about how studying with their fellow tribe members made the students feel.

This is Dr. Adcock interviewing an alumna named Ethel Moose Jackson.

Trey Adcock (from video): Why is it important for us to remember — in your opinion, there is no right or wrong answer — but why do you think it’s important that we preserve the history of the school?

Ethel Moose Jackson: Probably because my children and even Esther, my younger sister, and my grandchildren will never experience that. We had a bond there. … It was a kind of a bond that we knew we were there for each other. And we talked to each other and played with each other. … And it kind of went away after we went to public school. We were kind of spread out, and we didn’t have that closeness anymore. So, it’s kind of sad, and I think my boys didn’t get the experience being with the Indian children, and neither did Esther. I mean, she did up to a point, but it wasn’t like going to school with them, learning with them, reading with them, having music with them. It’s hard to explain if you never got to experience it yourself, you know, it’s hard, it’s hard to tell people. But I miss it.

Chuck Reece: The fondness of those memories is clear in Ms. Jackson’s voice. But Dr. Adcock is careful to note that Snowbird didn’t provide an experience so positive it was the polar opposite of the boarding school experience.

Trey Adcock: I don't want, you know, anybody that’s listening or reads about, you know, the Snowbird Day school to think that, you know, it was, you know, a pristine paradise that was just a separate experience altogether from the boarding schools. I mean, the intent was still the same.

There are stories that, you know, are very much similar to what happened at the boarding schools. I mean, there was physical punishment. There were some, you know, pretty deplorable teachers in that school. … The difference was those kids went home and told their parents who stood up at the school the next day and said, you know, basically, don't touch my kid, you know?

I think part of the story of the Snowbird day school is, you know, for me, just, you know, thinking about it over the years is really the way in which the Snowbird community exerted control over that school.

Chuck Reece: The report of the federal boarding school initiative calls for the government to invest in what it calls “community healing.”

Dakota Brown believes one path of healing includes giving her people the platform to tell their stories more broadly.

Dakota Brown: For our stories and our histories to be told, I think that we have to be the one to tell them. And as we, as more and more Native people obtain higher education, obtain their degrees and things like that, we are the ones that are becoming the historians that are going to be telling these stories. We're the ones that are going to becoming the political leaders that are creating access to this…

They're going to make sure that our stories are told. They're going to make sure that, we get to some sort of reconciliation. And I think that for me, it's much less about having a reconciliation on a national level — for the nation — And more about our own communities being able to heal from the traumas, the intergenerational traumas that we're still dealing with today.

And I think that that is starting to happen, but it's because we are taking control of those things. We're taking control of our medical care. We're taking control of how we approach mental health. We are absolutely, taking control of those types of things so we can come to some sort of place where we can heal from all of these traumas. And for me, that's what's most important.

Chuck Reece: I mentioned at the top of this show that before Dr. Malinda Lowery came to Emory University, she directed the Center for the Study of the American South at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, a wonderful resource for people who study our region.

So I asked Dr. Lowery how we should think about the centuries of trauma visited upon Native peoples in relation to the history and culture of the South.

Malinda Lowery: Just taking my liberty for a second as a historian and thinking about the South and, and thinking about, like, you know, what are those sorts of ethics of hospitality, for example, that Southerners are so known for? Not just white Southerners, but every kind of Southerner really is known for this. Those ethics of hospitality maybe come more from African and Indigenous people on this land than they do from Europeans on this land.

As a historian … I'm very lucky to be able to have access to some facts that not everybody has access to who's had a kind of a typical education around U.S. history, right, or southern history. … I can I've spent a lot of time with these facts, often that are kind of outside the mainstream layer of consumption. And so I, I love it when people are a little bit surprised when, when they hear a story that they've never heard, for example. About a Native person, or a Black person, or a white person who did something totally counter to the narrative, right?

Chuck Reece: The stories American schoolchildren have been taught about our founding fathers rarely reveal their flaws. We can all quote Thomas Jefferson’s notion that all men are created equal and endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights — life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. But few of us were taught about how Jefferson, in that same document, specifically excluded Native Americans from his idea of equality.

In today’s public discourse, some people say we should not be reminded of those flaws, that it is somehow incorrect to discuss any unpleasant truths behind the common historical stories.

Here’s Malinda Lowery again.

Malinda Lowery: To talk about our critiques of historical actors as political correctness is so disingenuous. … We need to understand that people have always objected to this treatment of Native people. Like since 1493, people were objecting, you know, and if we don't know about those folks who objected, we need to really be asking ourselves, well, what are we learning? I mean, how has this gotten twisted around to where we think that these objections that are now being registered are new? … The historical record is riddled with them — people saying it's not okay or ethical or godly or, you know, whatever phrase for morality you want to use. It is not okay to treat people this way.

I think it's slowly dawning on people because the information is finally getting out there. But all it takes is for you to put yourself in the shoes of somebody, some family or some child that has had to go through this, to realize how ludicrous it is to imagine that education requires this kind of trauma. You know it doesn't.

There's nothing about education that should be painful.

CONCLUSION:

Chuck Reece: We’d like to thank Trey Adcock, Malinda Maynor Lowery, and Dakota Brown for their help and cooperation in producing this episode. We also need to tip our hat to Annette Saunooke Clapsaddle, a member of the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians, a Salvation South contributing writer and the author of an amazing novel called Even as We Breathe. Annette graciously introduced us both to Trey and to Dakota.

And finally, we need to give shouts out to two North Carolina museums: the Museum of the Cherokee People and the Junaluska Memorial & Museum, where all the stories collected by the Snowbird Day School oral history project now reside.

You’ve been listening to Salvation South Deluxe, proudly produced in cooperation with Georgia Public Broadcasting and its network of twenty stations around our state. Every Friday, we add a new three-minute commentary about Southern stuff to our podcast feed, and every month or so, we add longer, dee-luxe stories, such as the one we’ve just told you.

I’m Chuck Reece, your host and the editor-in-chief of Salvation South, which you can find twenty-four-seven at SalvationSouth.com.

Jake Cook is our hard-working producer and the composer of our theme music. GPB’s director of podcasts is Jeremy Powell, and none of this could have happened without wonderful people like GPB’s Sandy Malcolm, Ellen Reinhardt and Adam Woodlief.

We’ll be back soon with another full-length episode of the Salvation South Podcast.

---

Salvation South editor Chuck Reece comments on Southern culture and values in a weekly segment that airs Fridays at 7:45 a.m. during Morning Edition and 4:44 p.m. during All Things Considered on GPB Radio. Salvation South Deluxe is a series of longer Salvation South episodes which tell deeper stories of the Southern experience through the unique voices that live it. You can also find them here at GPB.org/Salvation-South and wherever you get your podcasts.