Caption

Charles McNair (left) and James "Shack" Thompson (right) at the Dothan High School Unity Reunion

Credit: Dennis Lathem

On this episode of Salvation South Deluxe: Chuck tells the story of the Dothan High School graduating class of 1972, the first integrated class in the history of Dothan, Alabama. Fifty years ago, Dothan High students did their best to navigate a social environment defined by segregationist Governor George Wallace, and profound racial tension. Fifty years later, two friends and alumni, a black student and a white student, came up with a plan to try to treat these long festering wounds, in the form of what they called a Unity Reunion. The result shows the power of what good faith, accountability and honest dialogue can do to heal even our deepest traumas.

Charles McNair (left) and James "Shack" Thompson (right) at the Dothan High School Unity Reunion

Chuck Reece: Say “Civil Rights Act” and most Americans will conjure up a black-and-white picture. It’s in all the history books. President Lyndon Johnson sits at the Resolute Desk, pen in hand, ready to sign a monumental piece of legislation that prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

Dozens of the bill’s supporters surround him, most importantly the Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King Junior, who stands directly behind the president.

President Lyndon B. Johnson signing the Civil Rights Act surrounded by supporters including Martin Luther King Jr. (1964)

Big moments like these are what Most of us think of when we think about this nation’s long struggle for racial equality. We overlook the fights that came before. And we forget what came after. We believe the Civil Rights Act was signed, and suddenly, Black and white children were attending school together. Cue the harmonious soundtrack.

I used to think that way myself. For decades, I’ve had a good friend — a writer, like me — named Charles McNair. Charles grew up in the small city of Dothan, Alabama, down in the southern part of that state, about a half-hour north of the Florida line.

Charles is a few years older than I, and I remember the first time he told me that his high school graduating class was the first racially integrated class ever in Dothan. In Dothan, high school covered grades ten through twelve, and Charles was among the white tenth graders who wound up in school with their Black counterparts in the fall of nineteen-sixty-nine. More than thirty percent of Dothan’s population at the time was Black. These kids would become the Class of Nineteen-Seventy-Two, the first integrated class to graduate from Dothan High.

I think my reaction was something like, “Wow! That’s cool!” I didn’t give it another thought, to be honest. Just one more moment in the South’s long journey out of its cruel, racist past. I made unfounded assumptions about the students, Black and white. I figured that they’d used their three years together to work through their differences by the time they graduated. I figured that when they came back together for a reunion every ten years, they would just celebrate what a groundbreaking group they had been.

How blind I was…

This is James Thompson, who was part of that Class of seventy-two. He usually goes by his nickname, Shack.

James “Shack” Thompson: Prior to integration, we had two high schools in Dothan. We had Carver High, which was the Black high school started back in the 1940s and it ended in 1969. And we had Dothan High School. That was the primary for whites.

I'm at Lake Street Junior High School. We are planning to go to Carver next year…. They had the best band in the state. And they had a great football team, so we were all planning to go. My sister graduated from Carver in 1968. We were all excited to go to high school. Lo and behold, we get this news announcement, said, Carver High School is gonna be closed. Everybody's going to be transferred to Dothan High School. We were like, what? Everybody was shocked.

Chuck Reece: This is my longtime friend Charles McNair.

Charles McNair: I won't speak for my other white classmates, but I can tell you with an absolute dead-on certainty that I was fatuous, fat, dumb, and happy in my little white world.

I couldn't tell you that Carver had a marching band, even if it was a good one, or if Carver had a football team. Even if it was a good one. It was a total blank space. The only thing we knew about Black people was that a lady came to the house to help Mama with the ironing sometimes, and that was it.

Chuck Reece: And the class reunions afterward? They certainly were not celebrations of racial unity. In fact, they were barely even integrated.

Here’s Shack Thompson again, remembering two-thousand-two, when he came to Dothan from his current home of Philadelphia for the class of seventy-two’s thirty-year reunion. North of four-hundred teenagers graduated that year.

James “Shack” Thompson: I did attend the class reunion for the 30th year, and unfortunately there were a handful of blacks there. I could count ten blacks for our 30th class reunion. I was very offended. Because people in Dothan boycotted. They didn't come. It was the whole year where we only had ten blacks there.

Chuck Reece: You’d hear that story, and you’d bet good money that the Dothan High class of seventy-two, all of whom are in their late sixties right now, would probably go to their graves without ever bridging the racial divide.

But you would lose that money. All of it. On this episode of Salvation South Deluxe, you will hear the story of how the members of that class, working together, finally built that bridge.

THEME MUSIC UP

Chuck Reece: I’m Chuck Reece, and welcome to Salvation South Deluxe, a monthly series of in-depth pieces that we add to our regular podcast feed, where we unravel some untold stories of the Southern experience by letting you hear the authentic voices that make this region truly unique.

THEME MUSIC OUT

SCENE ONE

Chuck Reece: To understand what it was like for the school kids who became part of Dothan High’s class of seventy-two, you have to understand the racial tension that coursed like electricity through the entire state of Alabama in nineteen-sixty-nine, when they were put into the same school.

Here’s Charles McNair again.

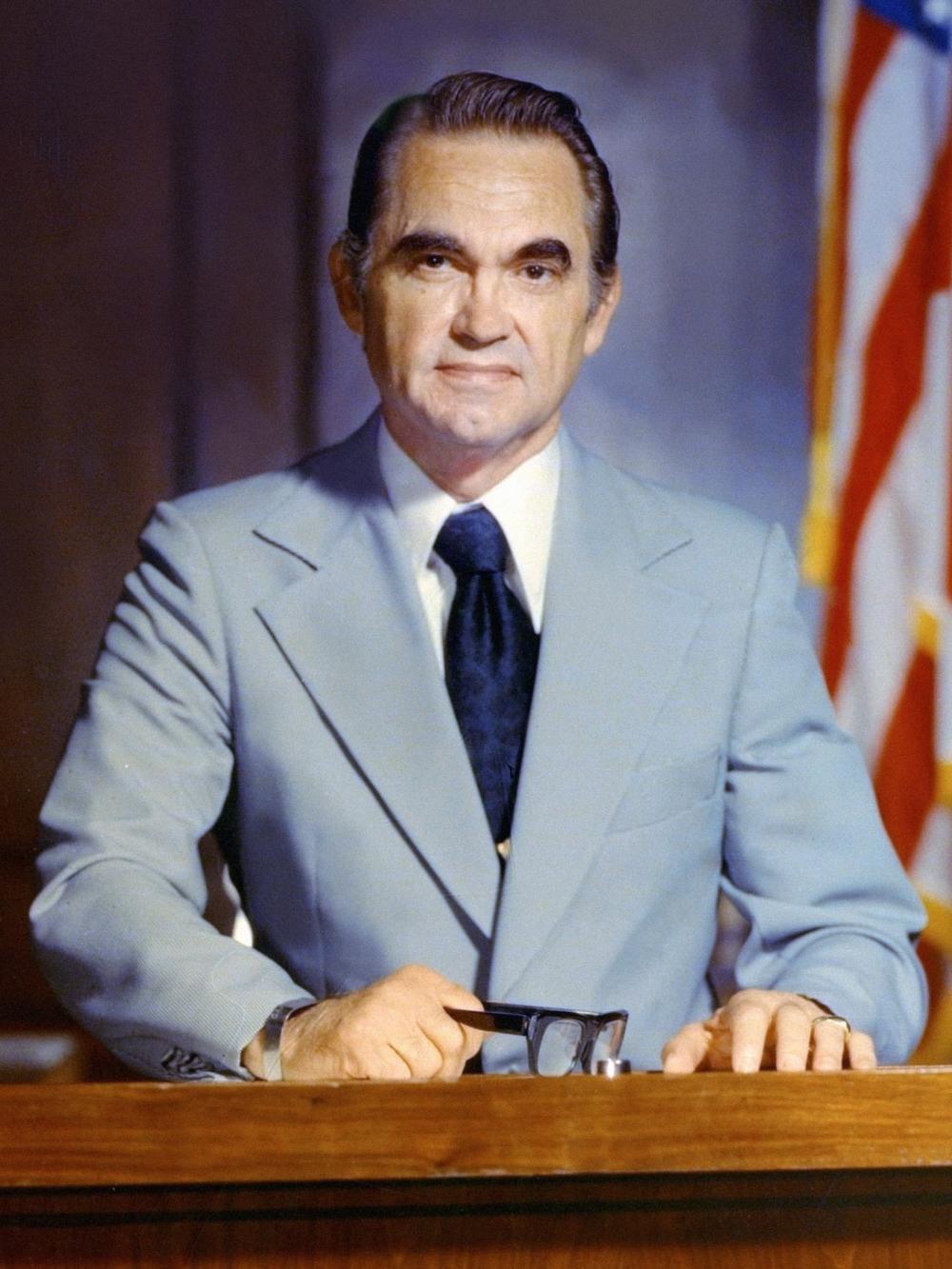

George Wallace, staunch segregationist, served four terms as the 45th governor of Alabama.

Charles McNair: This was George Wallace Country. And it was overwhelmingly pro segregation. You grew up indoctrinated into that. You didn't even know enough to ask questions about whether it was right or wrong. It's just the way it was.

How was I supposed to question whether that was right or wrong, when every single adult you knew and every single person in authority that you knew — your ministers, your teachers, your mom and daddy, grandmom and granddaddy, every single person — assumed that's what the world should be like?

Chuck Reece: George Wallace was sworn in as the governor of Alabama in January of nineteen-sixty-three, having won the office under this campaign slogan.

George Wallace: I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny, and I say, segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever.”

Chuck Reece: To the white citizens of Dothan, racial segregation was simply accepted. It was the way of their world. It was what they had been taught by their parents and grandparents. This is Dan Ponder, one of the white members of Dothan High’s first integrated class.

Dan Ponder: I was blessed to have … great grandparents alive when I was 20 years old. And one of those was the son of a Confederate veteran. I mean the "noble cause". The "state's rights". I grew up believing, you know, "Dixie" was a sacred song, and I guess I just focused on the feel-good parts of being a Southerner and never really addressed the horrors of being a Black southerner.

Chuck Reece: Here is Shack Thompson again, to explain how one of his own aunts experienced those horrors.

James “Shack” Thompson: My mother's sister was a domestic, meaning she worked for one of the white families in town. I mean, she cooked, she cleaned, she ironed.

She tells a story that one day, the owner, the man of the house, came and asked if she would do some ironing for him. She said sure. So he gave her this thing to iron, and she set up the ironing board. She ironed it without any questions asked, and halfway through the ironing she realized what it was. It was a KKK uniform. The sheet and the hat. Well, what could she do? She completed her ironing and she gave it back to him, starched and ironed, and he said thank you. And that was it.

Chuck Reece: Hearing the members of this class today describe the world of the late sixties in the South feels almost like reading a dystopian novel. But Dothan wasn’t an imaginary place, a fictional setting for an unsettling story.

It was a real city, where white students had been taught from birth to accept lies as truth: that their Black neighbors were by nature inferior, that their ancestors who fought to maintain slavery had been noble warriors, not traitors, and God intended his children on earth to be segregated by skin color.

Black students in Dothan saw and felt the hot sting of white supremacy every day, and felt, justifiably, that to challenge it, to resist it, would be to put their lives in danger.

LaPhyllis Heard was one of those Black students. If she had finished junior high a few years earlier than nineteen-sixty-nine, she would have spent her high-school years at Carver High, which all African American students like her attended.

But in the summer of sixty-nine, the Dothan city government finally decided, after fifteen years of delay tactics, to comply with Brown versus Board of Education, a nineteen-fifty-four U.S. Supreme Court ruling which declared that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional.

The Dothan government didn’t even make the decision until two weeks before the school year was scheduled to start. The city’s population at the time was about thirty-five thousand, about two-thirds white and one-third Black.

And it would be the first time LaPhyllis had ever shared a classroom with white students. Her parents had little advice they could give her.

LaPhyllis Heard: My parents didn't prepare me for that. … I don't think they sat me down and talked to me, prepared me for anything. I did what I could for myself.

Chuck Reece: LaPhyllis Heard says her parents had raised her with the golden rule, to treat people the way she hoped they would treat her. So that’s the attitude she took into her first year at Dothan High. Quite often, she says, others treated her accordingly. But sometimes, she was not treated well.

LaPhyllis Heard: Sometimes I felt intimidated. You know, I felt like they maybe didn't like me or they wasn't crazy about my Black skin.

I was sort of like an independent little teenager. You know, I’d go downtown to the shops in high school and some of the people will, you know, maybe make me feel like, “We don't want to say nothing to you. You stay on your side and don't speak.” You know, we went through that.

Chuck Reece: Christine Vineyard’s parents, on the other hand, were “trailblazers,” to borrow Christine’s own description. A few years earlier, when it was time for Christine to move from elementary school into junior high, Dothan’s government gave Black parents who wanted their children to attend primarily white schools that choice.

Christine Vineyard: Everybody was saying, okay, you can go to any school you want to go. So everybody went back to their sides and said, okay, well, we're going to continue doing what we're doing, right? My parents said well, we're going to try something different.

Chuck Reece: So they sent Christine to Girard, a white junior high. She was one of only three Black students there. Thus, in the summer of nineteen-sixty-nine, when Dothan High integrated, Christine was one of the few Black teenagers who had experience going to school with white classmates.

Her memories are not good.

Christine Vineyard: I probably had a lot of mixed feelings. Because I went to a white junior high school, the Blacks didn't like me, and, of course, the whites didn't like me. I felt like I was all alone.

Chuck Reece: Here’s Shack Thompson again.

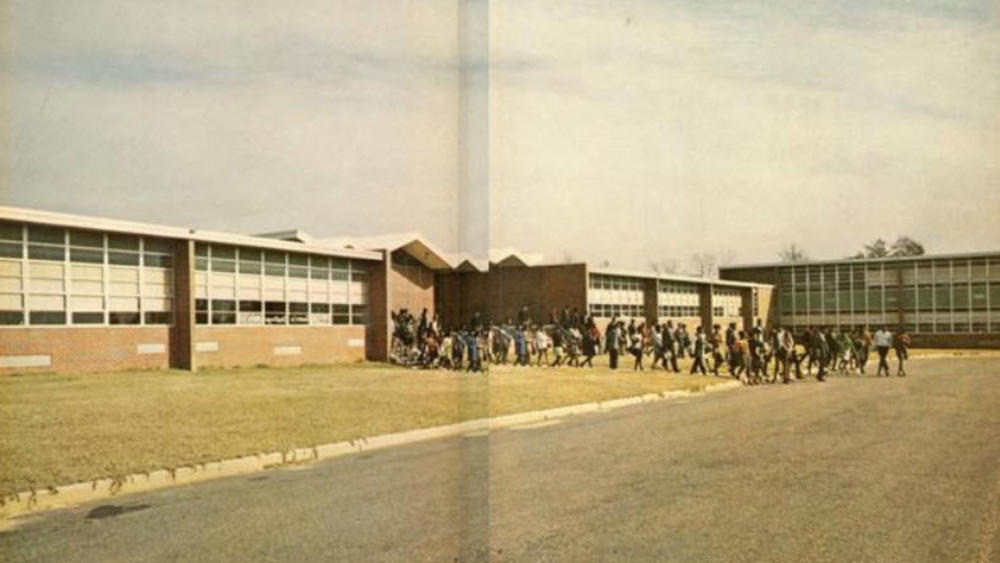

Carver High School closed in 1969 when Dothan, AL high schools integrated.

James “Shack” Thompson: Imagine Carver High School, a proud black high school, and they had honor society, they had science club, they had a football team, they had a band. They had all this stuff, but it went away. So if you were in the honor society of Carver High School when you got to Dothan High School, they put you in regular classes, not honor classes. If you were in the band, Carver High School, when you got to Dothan high school, they put you in the B band. Not the big Dothan High Band. Everything was second class citizen. You can imagine how people felt. If you were somebody at Carver, you were nobody at Dothan high school.

Chuck Reece: After they graduated in seventy-two, the Dothan High students did what most high school graduates do: they scattered in hundreds of different directions.

Charles McNair and Dan Ponder stayed in the South. McNair a few years ago married a woman from Colombia and today lives in Bogota, but he spent most of his life in Atlanta. Ponder today is retired and living in the city of his college alma mater, Auburn, Alabama, after spending most of his career in Georgia.

Despite being raised to accept white supremacy as the norm, they have both worked to, as we say, get above their raising.

Charles McNair: I had sleepwalked through the experience of high school. … There was so much more to be understood and to be felt and and to have compassion about. And all those years that I had avoided it — you know, fat, dumb and happy. I said that before. My little world, my bubble. … I realized that bubble had to go. That there was there was a lot more at stake than just, you know, my obliviousness.

Chuck Reece: By the time Ponder was twelve years old, he knew he could not square what his ancestors taught him with what he learned while playing baseball in Cottonwood, Alabama, the little town just south of Dothan where he grew up.

Dan Ponder: I went to school in Dothan, but I lived in Cottonwood and, you know, it was just a little town. There weren't really many summer sports other than baseball. And the town wasn't big enough to have baseball teams without Black and white boys playing together. And I interacted a lot more than maybe the typical boy my age coming up. But it was the institutionalized racism, the things that I just didn't think about.

To this day, I remember after baseball, walking by the Holleen City Cafe and saying, “Let’s go in and get a Coke.”So we're like 11 or 12 years old. And they looked at me like I was crazy. And they said. “We can't go in there. We have to go around back and sit at the picnic table.” Which didn't even have a umbrella on it. It just slammed me right there, you know, that they lived a different life.

Chuck Reece: While in Georgia, Ponder lived in Donalsonville, a little town that sits in the southwestern corner of the state, where it meets both Alabama and Florida. In nineteen-ninety-six, he was elected to the Georgia House of Representatives.

In two-thousand, Ponder gained some national notoriety when he did something you might not expect a Republican legislator from a conservative, rural Georgia district to do. The House was debating whether to pass the first hate-crimes legislation in the state’s history. The House was deadlocked over the bill when Ponder stood up and pledged to support it. In doing so, he told a story from those days he spent playing ball with his friends in Cottonwood. The story was about an interaction with his family’s Black caretaker. Here’s a little bit of what he said that day:

One day, when I was about 12 or 13, I was leaving for school. As I was walking out the door she turned to kiss me goodbye. And for some reason, I turned my head. She stopped me and she looked into my eyes with a look that absolutely burns in my memory right now and she said, ‘You didn’t kiss me because I am Black.’ At that instant, I knew that she was right. I denied it. I made some lame excuse about it. But I was forced at that age to confront a small dark part of myself… Hate is all around us. It takes shape and form in ways that are somehow so small that we don’t even recognize them to begin with, until they somehow become acceptable to us. It is up to us, as parents and leaders in our communities, to take a stand and to say loudly and clearly that this is just not acceptable.

Chuck Reece: Ponder’s colleagues in the House gave him two standing ovations. This is the voice of Gerald Bryant, reporting that day in two-thousand from the floor of the Georgia House, for GPB’s long-running television show, Lawmakers.

Gerald Bryant: We have the final passage there, yeas 116 and no's 49. So Senate Bill 390, the hate crimes bill has passed.

Chuck Reece: Dan Ponder’s speech brought tears to the eyes of some of his colleagues. And it turned a deadlock into a seventy-thirty margin of victory. Georgia's first hate-crimes legislation went into the books. Shortly thereafter, Ponder left politics and returned to his private business, running restaurants.

But three years later, in two-thousand-three, Ponder traveled to Boston to accept the John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award for that speech.

Dan Ponder: So I gave that speech, and a year later, I had received 25,000 letters. And they were all about the ways that people had been impacted by hate. … A small minority of people who thought that I was a lunatic or, you know, that murder is murder and hate doesn't have anything to do with it or whatever. Well. I say baloney to that, you know.

Chuck Reece: After this short break, we’ll be back to tell you how all these members of the Dothan High class of seventy-two united to say baloney to the racial tensions of their high-school experience a half century ago.

MIDROLL BREAK

SCENE TWO

Chuck Reece: Although Shack Thompson is a retired FBI agent, he is also a writer. And it was through writing that he first bonded with Charles McNair a half-century ago at Dothan High. When Charles was the editor of the school paper, The Scribbler, Shack’s English teacher submitted a poem he had written, and it was published.

James “Shack” Thompson: That started our friendship and I never forgot it. … He was always friendly too. He never treated me any different than anybody else. I never picked up anything there that we couldn't be friends.

Chuck Reece: Even so, Shack and Charles didn’t stay in close touch in their adult lives. But in the early teens, before Charles had married and moved to Colombia, while he was still living in Atlanta, he got a call out of the blue from Shack.

James “Shack” Thompson: I’d typically fly into Atlanta, rent a car, then I’d go visit my mom in Alabama. That's what I typically do. So I found out Charles was there, and I reached out to him, and he graciously invited me over to his house. We had lunch. He picked up the tab and we had a lot of conversation.

Chuck Reece: Over that meal, Shack looked ahead to twenty-twenty-two, when their class was due to celebrate its fifty-year reunion. Shack told Charles he was interested in staging the reunion, but in a way that was unlike any previous attempts at getting the class together.

What Shack envisioned, he said, was a “unity reunion.”

Charles McNair: he seed was planted, and I began thinking about it just the way he had been thinking about it. A few years went by. I had business in Philadelphia … and came up to visit. And Shack and I met in King of Prussia, where he lived just north of town. This was 2019. Three Years before the 50th reunion of the class of 72.

Chuck Reece: In the years between their lunch in twenty-thirteen or -fourteen and that visit in Philadelphia years later, a true friendship blossomed between Shack and Charles.

James “Shack” Thompson: When I reached out to him, I felt like I was calling a friend, and he knew exactly who I was when I callED. He said, “Shack, let's get together.” I said, “Absolutely.” …. We had a great time, and it made me realize that I wished we had stayed in contact all those years because he was a true friend.

Charles McNair: Shack is easy to like, he's easy to be a friend. … When you look back from that moment, the 40 years that I didn't know this wonderful guy, and think of why that happened. The wedge of race that had been driven between so many of us.

One thing we discovered as we began planning and actually, launched this, this 50th reunion, was that absence. It became so magnified and pronounced that, wow, all of these people and all of these lives and all of these friendships that could have, shoulda, woulda in a different world, in a different context, where we grew up in different circumstances.

Chuck Reece: Fifty years ago, the rules of Southern society had kept them apart. The passing decades left both men pondering, Just what did that cause us to miss?

Charles McNair: We began to see that putting it back together could at least salvage some of it.

Chuck (from interview): Wow. You agree with all that?

James “Shack” Thompson: Yeah. And, you know, it was just the two of us. We had no idea IF it was going to work. I mean, we had a hope and a plan. We had no idea that what we were thinking about, other people felt the same way.

Charles and I started with a plan to come up with a planning committee of different people. Balanced number of blacks and whites, males and females, with the same mindset. To form this new model. And believe it or not, we worked on this planning committee for 18 months.

Chuck Reece: All of the other Dothan High grads we’ve spoken to during this episode — LaPhyllis Heard, Dan Ponder, and Christine Vineyard — were recruited to be part of that planning committee, which soon grew to about twenty people.

James “Shack” Thompson: The most important thing we did, Chuck, was that we realized that a lot of the black students from Dothan High School started out with us in the 10th grade did not make it. … Somebody got pregnant. Somebody dropped out. Whatever reason, they didn't make it. So we decided even if you started out with us in the 10th grade and you did not make it, you were invited to come to the reunion.

We made people feel welcome. Look, you start out with us in the 10th grade, ninth grade, you are going to come to the reunion and nobody is going to judge you. That was a big deal to make it more inclusive.

Charles McNair: One of the most important signals that we sent was that when we began our outreach, the communications outreach, we wrote letters that were cosigned by a black classmate and a white classmate. The first one, Shack and I did it. That letter, went to, 18 months in front of the reunion. And it mentioned up front, absolutely, the idea that this was a unity reunion. … That was the mission. And we and we always kept the mission in front of us. And I think the signal that went to people was that, okay, guess what? After all this time, here's a chance to fix things. Here's a chance to, you know, to use a level playing field to sort of start fresh and, and, that that's exactly what happened.

Chuck Reece: The class of seventy-two had somewhere north of four-hundred-and-twenty members. LaPhyllis Heard, who had long since moved to Georgia, where she is now retired, had spent her life working first as a pharmacy technician and then in retail management. When she joined the reunion committee, she brought with her a belief she’d held throughout the last half-century: that the best of her classmates had started learning how to surmount the barriers of race while they were in school.

LaPhyllis Heard: We learned something. All of us did, the three years that we was there. I felt like we actually learned something. We learned how to deal with each other. Deal with differences, you know.

Chuck Reece: That belief, she told me, helped her overcome her innate shyness and throw her whole self into the committee’s outreach work.

LaPhyllis Heard: At first I was a little nervous and afraid because I was always a shy person. And but I wanted to take on that challenge. I remember saying, I'm afraid to dip into being on the planning committee, but I feel like I need to do it. I got to do it.

Maybe somebody would think I was naive to think that way, but I felt like, if we do the work, we go out with social media in and try to find these people and try to look them up. I just feel like we put our all in doing that, that it will be a big success. I feel like we will overcome. I really did.

Chuck Reece: After college, Shack Thompson became a schoolteacher and in the early eighties. He taught in the Dekalb County Schools near Atlanta. In nineteen-eighty-four, he switched careers and joined the FBI, where he worked until he retired. Since ninety-five, he has lived in the Philadelphia area.

When he began tracking down and talking to his Dothan High classmates, he was very direct. He never tried to paper over old resentments. After all, he had his own, about what he and his Black classmates lost by missing the experience of Carver High.

James “Shack” Thompson: We decided to start contacting people by sending letters, text messages, emails, face to face contact, staying in contact with people and by being transparent. We never acted like those bad things didn't happen. We accepted those bad things. We said, feel free to tell us your story, good, bad or indifferent. So we had a level playing field to start with.

Chuck Reece: Dan Ponder said the committee members quickly learned that before they could reach out in unison to more than four-hundred classmates, those lingering resentments had to be acknowledged, even among the committee members themselves.

Dan Ponder: I think that despite a lot of progress, racism is still alive and well. And there were, you know, a lot of wounds still. … We lanced some old wounds right there on the committee to begin with, people airing their grievances from 50 years ago and realizing, you know, we have to be mindful of this.

Chuck Reece: As they began their outreach to classmates, they had to address lingering anger.

Dan Ponder: You can feel it in their voice, their tone. And they would talk about, you know, well, we lost our band. We lost, you know, our our mascot, the name of … and they did. They lost everything.

You have to you have to try to put your arms around that. You can't you can't heal part of the wound. You got to heal all the wound.

Chuck Reece: Christine Vineyard, who had felt disdain from both her Black and white classmates at Dothan High, once believed the wounds could not heal. After she graduated, she got out of the South as quickly as she could. First, to college at the University of Oklahoma, where she eventually earned a master’s degree in environmental science. She began working for the Environmental Protection Agency in Texas. She still hasn’t retired from her job at the EPA, but she now lives in a small California town in the shadow of Mount Diablo, east of San Francisco.

As Christine began working to recruit classmates to come to the reunion, she acknowledged their resentments and eventually found her own melting away.

Christine Vineyard: People on the committee were very solicitous of everybody and wanting to make sure that everybody, you know, felt welcome. So I took my list and I talked to people and sent them information and that kind of thing and tried to promote it as, we need to leave the past in the past and let's enjoy life. You know, we've known each other over the years, so why can't we get together and break bread and have a dance and that kind of thing?

Chuck Reece: The more classmates she talked to, Vineyard told me, the more she found people who felt the same way.

Christine Vineyard: Everyone seemed to be on the same page as far as how they wanted, you know, the reunion to gel. They wanted something that everyone could feel good about and be a part of and wanted to feel included. I think that was our major goal, was to reach out to everyone that we could and say, you know, we want you here. You were in our class. We just want to get the whole class together and just, you know, have a fun time.

Chuck Reece: When the weekend of the reunion arrived in twenty-twenty-two, more than two-hundred class members showed up. Throughout the months of planning, the committee had cataloged eighty-four classmates who had died.

Charles McNair: It took all of us getting old, and it took 84 of our class members going on to the great beyond, before we all managed to get together in this one place and treat each other the way we always should have treated each other.

Attendees of the 1972 Dothan High School Reunion, aka the Unity Reunion

Chuck Reece: On the second night of the reunion, Saturday, all those who had died were memorialized. Dan Ponder remembers the night vividly.

Dan Ponder: The memorial section came along. The audio was not working on the video. And everybody's still talking. It's loud. Then it slowly gets quiet as people realize what's going on and then it's nothing but the screen and their name. And it … it just became silent. And then you would hear, you know, I remember her. Or just kind of a collective awe.

And then it’s, it's kind of like being in church where, you know, the preacher has connected or that song has connected. You know, there's just this kind of connective unity that doesn't require words.

Chuck Reece: And then, losses acknowledged, they did what people do at every high school reunion.

Dan Ponder: They danced. I mean, it was dancing like they're releasing things. In reality, everybody was just having a great time. People out there with canes dancing. I have enjoyed every reunion we went to, but this was just different.

Chuck Reece: Today, the class of seventy-two reunion committee is still meeting, once a quarter, over the internet.

Charles McNair: We are compiling at this moment stories from seniors of 72. And we're going to do a book, a compilation of these stories that will be presented at the, at the 55th anniversary. We're going to do them every five years now because we're dropping like flies.

Chuck Reece: In the two years since their fiftieth-anniversary reunion, twenty-five more classmates have passed away.

Charles McNair: What we keep saying to each other and I marvel at is the realization of how rich it is to connect with people after 50 years, that we're on the other side and what you missed and what you learned and how beautiful their lives have been and how and that tremendous that somehow we all had not allowed to happen to ourselves just because of, you know, the skin tone.

James “Shack” Thompson: Before we had this reunion there were shootings all around the country. At different places, grocery stores, people being shot wherever. So some people were afraid that there was going to be violence. … But there was no weapons. There was no guns. There were no fights, no cursing, none of it.

Charles McNair: In the subsequent planning committee meetings there was an exhilaration. And a jubilation, a celebration of what had been accomplished. And that wave is still rolling. It has not dissipated, even though now it's been two years since the actual reunion.

What we made happen is still there. There's a fervor. It is. It's like a revival. And it's so beautiful that, you know, you can feel the love in the room in the zoom calls. As cliche as it sounds. But there's not one of us on those calls that doesn't really, truly love one another for what we were able to do and what we're going to do. Don't you think that's right, Shack?

James “Shack” Thompson: Yeah I do. I think it's amazing.

OUTRO

THEME MUSIC UP AND UNDER

Chuck Reece: We’d like to thank James “Shack” Thompson, Charles McNair, LaPhyllis Heard, Dan Ponder, and Christine Vineyard for their and cooperation in producing this episode. We also want to thank the staff of the long-running GPB television show, Lawmakers, which for over fifty years has reported daily on the activities of the Georgia Legislature. Without their amazing archive, we could not have found the recording of the moment when Georgia passed its first hate-crimes legislation almost twenty-five years ago.

You’ve been listening to Salvation South Deluxe, proudly produced in cooperation with Georgia Public Broadcasting and its network of twenty stations around our state. Every Friday, we add a new three-minute commentary about Southern stuff to our podcast feed, and every month or so, we add longer, dee-luxe stories, such as the one we’ve just told you.

I’m Chuck Reece, your host and the editor-in-chief of Salvation South, which you can find twenty-four-seven at Salvation South dot com.

Our producer is the mighty Jake Cook, who also composed our theme music. GPB’s senior podcast producer is Jeremy Powell, and none of this could have happened without wonderful people like GPB’s Sandy Malcolm, Ellen Reinhardt and Adam Woodlief.

We’ll be back next month with another full-length episode of the Salvation South Podcast.

Salvation South editor Chuck Reece comments on Southern culture and values in a weekly segment that airs Fridays at 7:45 a.m. during Morning Edition and 4:44 p.m. during All Things Considered on GPB Radio. Salvation South Deluxe is a series of longer Salvation South episodes which tell deeper stories of the Southern experience through the unique voices that live it. You can also find them here at GPB.org/Salvation-South and wherever you get your podcasts.