Section Branding

Header Content

The borderless music of Gabriela Ortiz

Primary Content

Composer Gabriela Ortiz has paid some dues — and now she’s collecting. Earlier in her career, she walked out on sexist professors, rebuffed condescending musicians and once waited hours to meet with a conductor in hopes of simply hearing her own music performed. In 2019, she underwent treatment for colon cancer, which is now in remission.

Today, the 59-year-old Mexico City native is enjoying some well-deserved recognition. Ortiz has just begun a year-long composer’s residency at Carnegie Hall, where her music and her programming will be heard in a variety of contexts. She’s serving in similar roles this season at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia and the Castilla y León Symphony in Spain.

She’s also cultivated a crushing schedule. In the past four years, Ortiz has premiered at least 10 major orchestral works, half of them championed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic and its star conductor Gustavo Dudamel, who has called her one of the most talented composers in the world and who will lead Ortiz's new cello concerto, written for Alisa Weilerstein, at Carnegie Hall on Oct. 9. Revolución Diamantina, a recent album of her works performed with Dudamel and his orchestra, has earned glowing reviews for how deftly it combines an array of musical languages, from high European modernism to the roots of Latin American folk.

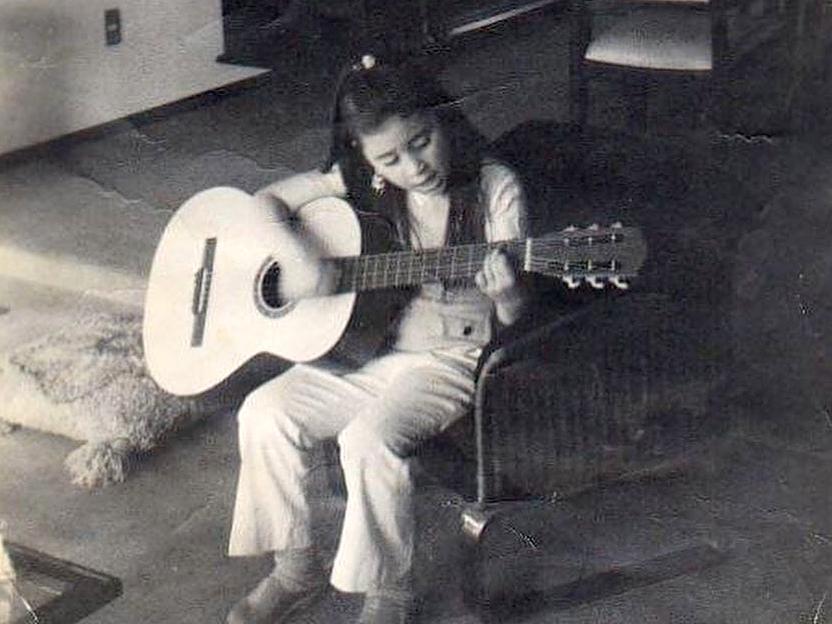

Music, and hard-won confidence, run in the Ortiz family. Her grandfather, a classical music enthusiast, moved to Mexico from Basque Country, Spain, and saw Gustav Mahler conduct in New York while living on the East Coast. Ortiz’s parents co-founded Los Folkloristas, the celebrated band dedicated to Latin American folk music and research, and she learned to play instruments in the group’s outreach learning center for children. With the piano as her primary instrument, Ortiz realized early on that the life of a concert pianist was perhaps beyond her reach — but the idea of composing blossomed after an early encounter with Béla Bartók’s music, and from there, nothing could stop her ambitions.

From her studio in Mexico City, Ortiz joined a video chat for a far-ranging conversation about the role folk music plays in her work, the importance of speaking your mind in your art, and what it really means to be a composer from Mexico.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tom Huizenga: I first heard your music in 1998 at a Kronos Quartet concert, where the group played Altar de Muertos. In the final movement of that piece, there’s a reference to an Indigenous music culture from Mexico — a Huichol folk melody from the state of Nayarit. That same melody has now appeared in at least two more of your pieces, including the recent Kauyumari. What attracted you to this folk tune?

Gabriela Ortiz: I first heard it on a Huichol recording. Normally I never use direct quotations, but in this case, because the melody was very attractive, I just had to use it. The [folk musicians] play a violin that only has two strings, so I harmonized that melody and developed it rhythmically. The melody repeats and repeats — and for the Huichol people, repetition is very important, because it's music you play in peyote ceremonies where hallucinations are a way to contact ancestors.

Your parents were founding members of the band Los Folkloristas, which specialized in Latin American folk music; was the use of that melody influenced by your childhood experiences?

No, I never heard Los Folkloristas play Huichol music. Normally, the folk music that we hear in Mexico is a mixture between European, Indigenous and African — those are the three main roots. This came later, when I got the recording from the Institute of Anthropology, and I just fell in love with it.

What was it like growing up in a household steeped in folk music?

It was fun, because some of the rehearsals took place in our house. My father was an architect, so we had a big house, and in the basement was a studio full of instruments — guitars, a charango and drums and different instruments, not only from Mexico but from Latin America. They had rehearsals in the evenings, and of course my parents said, “Go to bed!” But I never went to bed; I stayed in the hall trying to listen to the music.

I also met important musicians, like Atahualpa Yupanqui and Mercedes Sosa, who came to our house. Also Victor Jara, the Chilean singer — the only time he came to Mexico, he stayed in our house. During the dictatorship of Pinochet, they captured him and cut off his hands. I remember my father crying when someone called to tell him that Victor Jara had died; he was shouting, “No, no!” and I didn't know what was happening. So yes, it was important for me not only musically, but also politically.

Did you ever play in the group with your parents?

Not in the group. Los Folkloristas had a school for people who wanted to learn folk music, so I played guitar and charango in the children's section. Sometimes I sat in with them for fun, but never in a concert hall.

Were you hearing any classical music in those early days?

Absolutely. My mother played piano for 18 years; she was a very good sight reader. And I remember my father took me to see a concert with Eduardo Mata, the conductor who was one of our greatest directors in the history of music in Mexico. He was conducting the London Symphony, and I remember that they played Manuel de Falla’s El sombrero de tres picos and I was like, “Oh my God!” I just loved it.

My father was an architect, but he wanted to be a classical composer. He couldn't do it because my mother died very young, and he got depressed and said, “Well, I don't know if I'm going to be a composer, but my daughter could be a composer.” So, suddenly he put all of his thinking into my career.

Whose idea was it for you to become a composer?

I remember when I was 7 or 8 years old, my mother said, “I'm seeing that you love music and you play the guitar. Why don’t you start learning the piano, and learn how to read music?” So I started piano lessons. When I was about 13 years old I changed to a new teacher, and this woman was like a Mexican version of Nadia Boulanger. She was a very good teacher of harmony and solfège, and she introduced me to Béla Bartók. At the time, I was playing Mozart, Bach and Schumann, but when I first heard Bartók’s music I said, “Wow, what is this?” I immediately had a connection, probably because of the rhythm and the modal language. It was a totally different thing. I said, “I want to write little pieces for piano like Bartók,” so I started composing for the piano. Then I realized, I'm not going to be a concert pianist — that's not my goal. I want to be a composer.

I feel like Mexico is still rather under the radar in terms of people knowing about its rich history in classical music. Carlos Chávez or possibly Silvestre Revueltas are the only composers many people know, even classical fans. Why is that?

There is no interest. When I was studying in England, they didn't know who Revueltas or Chávez was. They didn’t care about what was happening in Latin America. Also, in Latin American institutions, you learn Western European music, basically. It’s part of the canon in all the universities. German Romanticism is strongly emphasized — Beethoven, Bach. But do we really know all of the contributions by Villa-Lobos or by Ginastera, or even by Revueltas?

Many young Latin American composers move to Europe, because they want their music to be played. They compromise their language because they are composing in a very European style. For me, that’s one of the other problems. I mean, of course, if they want to compose like that, it’s OK. But many of them compose in the spectralism style, like that of Tristan Murail or Helmut Lachenmann.

You teach at the National Autonomous University in Mexico City. Do your students choose to compose in that European style?

Some of them. Of course, if they want to compose like that, there is nothing that I can do — I have to respect their freedom, and I can only speak for myself. That style doesn't work for me; I don't belong to that. I was not born in Germany, so why do I have to compose like Lachenmann or Wolfgang Rihm? I'm totally different.

This leads me to wonder: What does it mean to you to be a Mexican composer? I think it was Virgil Thomson who was once asked how you define American music, and he said: “It’s music made by someone with an American passport.” Is it that simple for you, or is there more to it?

This is the most important thing: When I do my music, I write what I have to say. I'm not thinking, “Okay, this is going to sound really Mexican” — never. If I use a Huichol melody, it’s because I really like it. But if I find a melody from Bali, maybe I will use it as well. What’s important is what you do with that.

It's very difficult to define Mexico, because Mexico is huge. It’s not the same in the North as in the South or the center. One of the main problems is that people try to put a specific label on Latin American music, and that's totally wrong because Latin America is so different — Argentina from Mexico, or from Venezuela, or the Caribbean countries.

I feel like your music has a singular language, but there are influences as well. First and foremost, I hear Stravinsky — those stabbing rhythms in your ballet Revolución Diamantina, also in Téenek and Clara. What draws you to Stravinsky?

Stravinsky is one of my favorite composers. He’s a genius. I still believe that The Rite of Spring is one of the most important orchestral pieces in the 20th century. There is a strong pulse and an irregularity in Stravinsky that I really like; you're always feeling that it's changing and giving you something new. Latin American music can be very regular, but if you analyze my music, rhythmically speaking, it’s very irregular.

You change meters a lot.

Yes, and this is something that I learned from Stravinsky. But you have to understand that we have the right to absorb those composers. The [perception] is, “Oh, you're a Mexican, so you cannot address Beethoven.” But Beethoven is universal. He’s as important to me as he is to the German people. I also come from this European tradition; the Spanish were here in Mexico. It's a big problem when you talk about borders in music. There are no borders. Mahler belongs to me. Why not?

And so do György Ligeti and Olivier Messiaen — I hear little essences of those modernist composers in your ballet, and in the violin concerto Altar de Cuerda. You’re agile at blending avant-garde and European classical traditions with Latin American folk styles. Do you have a sense of what your own music sounds like?

It’s difficult to explain in a rational way, but it comes very natural. I’m absorbing everything. It's just there, it's part of who I am, and Debussy is as important as Perez Prado or mariachi music. If I need to have that kind of influence for a specific reason, I will use it. For example, in the fifth movement of my ballet — the protest section — there is a samba. But it's not there because I want to sound Latin American by using a Brazilian samba. There’s a political reason to use it.

I find the element of rhythm is so strong in your music. In works like Kauyumari, Yanga, Téenek and especially the trumpet concerto Altar de Bronce, the beats make you want to shake your hips.

I like to work with rhythm; it comes naturally. And I like to dance. Probably, in my past life, I used to be a flamenco dancer.

How did some of these rhythms get to Mexico in the first place?

From Africa. People forget that in the 16th century, there was a very strong African influence in Mexico, and immediately the African slave population mixed with the Indigenous populations and with the Spanish. All these cultures mixed together was very strong in Mexico — a melting pot. If you go to Vera Cruz, you dance danzón. There are so many things that stem from Africa.

So you have all of these Afro-Cuban and Indigenous Latin American rhythms in your music. How hard is it to get orchestral musicians, steeped in Brahms and Beethoven, to play those grooves with soul?

If the music is well-written, it’s going to speak. I mean, you don't have to be Russian to play The Rite of Spring. You don't have to be Hungarian to play Bartók. I remember hearing Beethoven by [Venezuela's] Simon Bolivar Symphony, conducted by Dudamel — and wow, what a version of Beethoven. Music is a universal language.

By my count, since 2020 you have had 10 major orchestral premieres — half of them conducted by Gustavo Dudamel — and that's not counting the world premiere of your cello concerto for Alisa Weilerstein, or your non-orchestral premieres. That’s a lot of music. What does that say about your career?

It's very exciting. If you had asked me this question 20 years ago, I would never have imagined that I would be in this position, especially here in Mexico. I don’t know how I did it, really. But I can tell you that I worked very, very hard. It was a unique opportunity when I wrote Téenek for Gustavo — that was my first piece for him, and I put all my effort into writing a good piece, because I knew that it was going to be something that would either open the door or close it.

Are you at the peak of your career right now?

I don't know, but I'm very happy right now, and I’ll tell you why: All composers need good performers to play their music. It is the only way we can learn, by listening to our music. That's why I talk to Gustavo about the need for a pan-Latin American initiative, because believe me, the opportunities here are 10 times harder than in other countries.

Why is that?

Because we don't have as many orchestras as you do in the U.S., or as many opportunities. When I was a student, I wrote my first orchestral work under the guidance of Mario Lavista. And I was desperate to hear my piece. There was no orchestra at the university, so that was not an option. But you know what I did? I went to the Mexico Philharmonic Orchestra — a professional orchestra — with my score in hand and I said, “I want to speak to the maestro.” They said, “Do you have an appointment?” I said, “No. I will wait.”

I stayed for two hours to speak with Herrera de la Fuente. We met in his office and I told him, “I want to hear my piece. That's all I need. I'm a student, I want to become a composer, and I want to hear it desperately.” He looked at the score and said, “We'll call you.” Three months later, I received a call: “We are going to play your piece.” That was the only way I could hear my music.

For me, the three pieces on your recent album with Dudamel leading the LA Phil mark a high point in your career. There’s the short orchestral show piece Kauyumari, the diverse and deeply considered violin concerto Altar de Cuerda, and the expansive, politically charged ballet Revolución Diamantina, which translates as “Glitter Revolution” in English.

This is why I love the LA Phil and Gustavo, because they asked me what I would like to write. [I said,] “I want to write a ballet.” And Gustavo said, “Why don’t you write something including choir, because we want to pair your piece with Beethoven’s Ninth.” I told them it was going to have a very political theme, that I needed to express the femicide situation that is unbearable here in Mexico. And they said, “Yes, do it.”

In the notes for the album, you mention that writing the ballet forced you to reach “beyond the aesthetic languages I know, by experimenting with new tools.” Can you say more about the strategies you had to learn in order to write this piece?

I was exploring things like whispering and amplified voices, not just singing — making noises, protesting and shouting slogans. Shouting things like, “Con ropa o sin ropa, mi cuerpo no se toca” [“With or without clothes, my body is not touched”]. It was totally out of my comfort zone; I never wrote music based on a street protest.

For example, the fourth movement — it’s very Stravinskian in some sections, but in others is the depiction of domestic violence. And I was trying to see how I could make the violence stronger and stronger in the music by raising the level of sound until you get to “pa, tu, pa, ta,” which represents the fighting. I was experimenting with the voices in a percussive way — very different in the context of orchestral music, and in the context of a ballet.

The themes of gender inequality in the ballet make me think of your orchestral work Clara, inspired by the pianist-composer Clara Schumann, the overshadowed wife of composer Robert Schumann. You’ve said about this piece: “Throughout history, women have had to overcome major obstacles marked by gender differences. There are many of us who have rebelled against these evident forms of injustice and struggled to gain recognition and a place in society.” That makes me wonder if you, yourself, have had to overcome similar obstacles as a woman composer?

Yes, sometimes. I remember I was very young, presenting a clarinet piece to a composition teacher, and the guy saw the score and he said, “Think about Clara Schumann and Robert Schumann. Robert is better. Think about Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn. Felix is much better. Think about Alma Mahler and Gustav Mahler. Gustav is better. Don't you think women compose like they’re cooking a recipe?” When he said that, I took my score and I left the room and never came back.

Almost every woman composer I've talked to has a story. Kaija Saariaho told me about professors who didn't want to teach her because she was pretty and would get married and have children. Meredith Monk recalled men who made her feel like there was something wrong with her because she had a vision of what she wanted to do. But both of them also said there was no way anyone could stop them.

That's correct. I mean, I was very angry, but he didn't stop me from writing music. I always face the problem of being a woman composer, but also a Latin American composer. I remember when I was in Darmstadt, Germany [a hotbed of experimental music], one performer came to me and said, condescendingly, “Oh, you're from Mexico — so you’re the kind of Mexican composer who works with melody and rhythm and harmony.” And I said, “Yes. Is there a problem with that?” I like music. And music is about melody, rhythm, harmony, chords — not only about texture and noise.

You must feel a certain sense of pride, and responsibility, now that you're taking on the position of Composer’s Chair at Carnegie Hall this season. What kind of freedom does this residency offer?

A lot of freedom. I proposed a series of concerts and they allowed me to collaborate with different ensembles, like the Ensemble Connect — that concert will feature Latin American music. If I can help promote these incredible composers, I will do that. We’re also doing an interdisciplinary project called Can We Know the Sound of Forgiveness, a collaboration with visual artist James Drake; the writer Benjamin Alires Sáenz from El Paso, Texas; Alejandro Escuer, the Mexican flutist; and The Crossing choir. I was able to propose that project, which was well received by the institution.

What kind of advice are you giving your students at the National Autonomous University in Mexico City who want to have a career as a composer?

I always tell them they have to work very hard and have a lot of discipline. Talent is important, of course, but it's not only about talent. You have to put all of your soul into your work. Every single piece has to be a winner, no matter if it's for solo clarinet or for orchestra. Another important thing is, they have to live their lives very intensely, because that's the fuel for your creativity, for life itself.

I have to tell you, I feel I made the right decision to stay in this country. When I finished my PhD in London, I was thinking maybe I should stay there because of the opportunities. I was also offered to teach at Indiana University and other places in the U.S. [But] I always thought that it was important for me to be here in Mexico. Because the Autonomous University is a free university — it’s tough to get in, but once you’re in, you don’t pay a single peso — so people come from many different economic levels. For me, it's important, because I feel that I'm making a contribution to my country and to my own people. I feel like I'm putting a seed in each of them.

What kind of advice are you giving to yourself these days, given how busy you are writing music and navigating your rising reputation?

Sometimes I think: “Why didn't this happen years ago? It's happening when I’m turning 60?” So I have to be very wise with my time. I have to take care of myself. I exercise — I'm wearing pants right now because I came from the gym. I have to live my life as well, every second. I have to enjoy the simple things. If I'm seeing a friend, I have to enjoy that moment. If I'm reading a book, I have to enjoy that.

Also, be sensitive about what's happening. Perhaps 10 years ago, I would have been more careful about the things I talk about, but not now. I'm in a position that if I need to talk about feminism, I will do it. If I need to talk about climate change, I will do it, because that matters to me. It's all a part of our life.