Section Branding

Header Content

'Cheat Code to Life': Jailhouse lawyers help incarcerated people — and themselves, too

Primary Content

When Jhody Polk entered a Florida prison years ago, she noticed something special about the women in the law library.

“They felt taller than the rest of us,” Polk said. “It was the knowledge that they had, the way they used legal language, the confidence that they had.”

Those women had no formal legal training, but they had figured out how to decode the law to help other people in prison. Polk soon joined them, in a move that would come to transform her life.

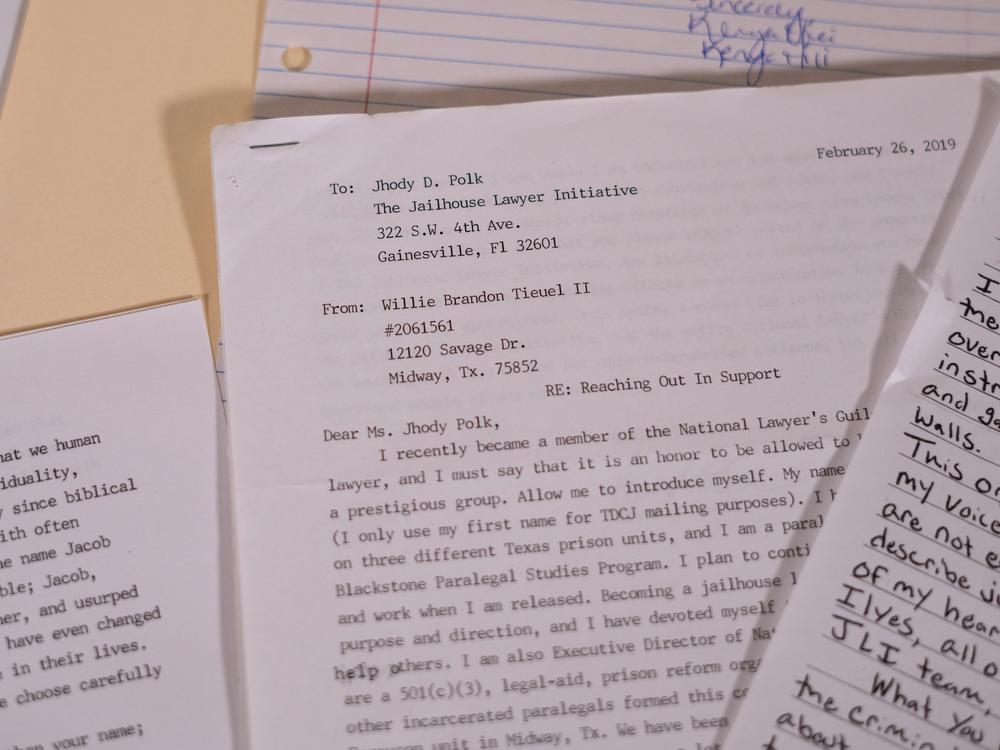

Out of prison since 2014 after serving time on several felony convictions, she’s working to introduce the world to these jailhouse lawyers. Her Jailhouse Lawyers Initiative, housed at the Bernstein Institute for Human Rights at the New York University School of Law, counts 1,000 members, across every U.S. state.

This week, they’re hosting a meeting in New York and launching a new web site. It’s filled with oral histories and more than 350 letters from people in prison who work with the law.

Their names may not appear on court briefs or judicial decisions. But behind the scenes, she said, incarcerated people have played a big role in the law for decades — something her initiative aims to bring to light.

“The first time I read a law book, it was like finding the cheat code to life,” Polk said.

Humanizing the time behind bars

One of those people is Brandon Tieuel, who found the law when he was incarcerated in Texas for 11 years in a series of prisons, including a maximum security facility.

“I’d go in there at like 8 o’clock in the morning and I’d be in there sometimes until 8 o’clock at night,” he said. “And I just fell in love with just reading the case law, learning the policies, and the statutes.”

Tieuel said prison can be dehumanizing. Authorities refer to you as “offender,” or by a number, not your name. But those long hours in the library found him writing complaints and prison grievances, helping challenge convictions, and preparing parole applications for other people.

Those moments gave him a boost, too.

“Once I started helping other people like on a big scale, like I just saw how it made my time a little bit better, it made me happier, because I was doing something worthwhile — and it just kind of snowballed from there,” he said.

Tieuel won parole last year. He now lives in Houston and works with families of people who are incarcerated.

Tyler Walton is managing attorney at the Jailhouse Lawyers Initiative. Walton said giving people tools to understand the law is “the right thing to do.”

“The law should be working for everybody, and the way that we’re going to move towards that is if everybody has a place to participate in the law,” Walton said.

Right to access courts

The Supreme Court enshrined the role of jailhouse lawyers back in 1969, in a case about William Joe Johnson, also known as “Joe Writs.”

He was a Tennessee inmate who helped illiterate fellow prisoners file legal petitions. Prison officials threw Johnson in solitary confinement for violating a rule that barred inmates from helping with legal matters.

The justices ruled that people in prison have a right to access the courts — but they did not require states to provide prisoners with attorneys. So jailhouse lawyers flourished inside prison walls, even if they remained invisible on the outside.

“When a jailhouse lawyer works on a case it’s pro se, and so their name is typically never mentioned inside of the appellate brief or the outcome," said Polk, the founder of the Jailhouse Lawyers Initiative. "There’s so many cases where there’s a jailhouse lawyer behind it, so many policy changes."

The vast majority of people who enter prison eventually return home. But jailhouse lawyers run into some big complications. They’re not allowed to practice law once they leave prison, because that’s typically controlled by state and legal officials.

“What we see is that jailhouse lawyers who often have developed these legal skills over decades, helping their community — as soon as they get out, they can be at threat for prosecution if they do the same work they were doing while they were on the inside,” Walton said.

He said there’s a huge need for people outside prison who can translate what happens inside—exactly what jailhouse lawyers have been doing for decades, to little acclaim.