Section Branding

Header Content

Deluxe: The Rot Under the Magnolias - How "Southern Noir" Literature Addresses Social Issues

Primary Content

On this episode of Salvation South Deluxe: Chuck Reece explores the evolution of Southern fiction through conversations with acclaimed authors David Joy, Tayari Jones, Michael Farris Smith, Chris Offutt and S.A. Cosby. From Appalachian hollows to Atlanta's streets, these authors craft thrilling narratives that challenge stereotypes and confront issues of race, class and justice.

EPISODE SUMMARY:

Dive into the gritty world of Southern noir with our latest Salvation South Deluxe episode. Join host Chuck Reece as he explores the evolution of Southern fiction through conversations with acclaimed authors David Joy, Tayari Jones, Michael Farris Smith, Chris Offutt, and S.A. Cosby. Discover how these writers are reshaping the literary landscape by giving voice to the disenfranchised and exposing the complex realities of the modern South. From Appalachian hollows to Atlanta's streets, these authors craft thrilling narratives that challenge stereotypes and confront issues of race, class, and justice. Don't miss this fascinating journey into the heart of contemporary Southern literature.

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT:

Fred MacMurray, from Double Indemnity: It was a hot afternoon, and I can still remember the smell of honeysuckle all along that street. How could I have known that murder can sometimes smell like honeysuckle?

Chuck Reece: The voice you just heard belongs to the late actor Fred MacMurray, playing an insurance agent named Walter Neff. A real hot number named Phyllis Dietrichson, played by Barbara Stanwyck, has lured Walter into a scheme. They’re gonna murder her husband for the life insurance money.

The movie is Double Indemnity. It came out in 1944. Film buffs say Double Indemnity was the blueprint for a style of movies the world came to know as “film noir.” Hollywood films from the 1940s and '50s. Always black and white. Always the femme fatale. Always sharp, snappy, cynical dialogue, like that line about murder smelling like honeysuckle. Or like this exchange between Lauren Bacall and Humphrey Bogart in The Big Sleep:

Lauren Bacall, from The Big Sleep: You know, I don’t know what there is to be cagey about, Mr. Marlowe. And I don’t like your manners.

Humphrey Bogart: Well, I’m not crazy about yours. I didn’t ask to see you. I don’t mind if you don’t like my manners. I don’t like ’em myself. They’re pretty bad. I grieve over them long winter evenings..."

Chuck Reece: I’ve loved those movies since I was a teenager. Still do. Then, several years ago, I heard a variation on “film noir.”

Back in the teens, I got a call from an old friend who knows my tastes. He owns a local bookstore. He told me he had two books for me. And he described them as “Southern noir.”

I liked the sound of that.

He told me he was throwing an event for the writers. He wanted me to read the books and interview them in front of a live audience. One was a Mississippi writer named Michael Farris Smith whose second full-length novel, Desperation Road, would soon hit the stores. The other, a writer from the North Carolina mountains named David Joy, was about to publish his second book, too. It was called The Weight of This World.

I fell in love with both books. I read the first sentence of David Joy’s The Weight of This World and have never forgotten it:

Aiden McCall was twelve years old the one time he heard ‘I love you.'

I know, right?

Michael Farris Smith’s Desperation Road also began with a dark, foreboding image. His first sentence was a little longer, but it hit just as hard: “The old man was nearly to the Louisiana line when he saw the woman and child walking on the other side of the interstate, the woman carrying a garbage bag tossed over her shoulder and the child lagging behind.”

After that, I dove deep into this new breed of Southern thrillers, suspense novels, call them what you will.

The film noir of Hollywood in the middle 20th century — and the books they were based on — were built on straight-up good guy vs. bad guy plots. Or bad girl vs. good girl. The only thing that made them different was their style, their dark moodiness.

These new Southern thrillers were shadowy, too. And they had the snappy dialogue. But the characters weren’t just plotting crimes. They were fighting for their lives as they dealt with issues that plagued the whole South: Poverty. Racism. Addiction.

Today, you’re going to meet five of the greatest practitioners of Southern noir literature — the aforementioned David Joy and Michael Farris Smith, plus the bestselling African American authors Tayari Jones and S.A. Cosby, and the Kentucky-born novelist and screenwriter Chris Offutt.

All of them are people whose writing will keep you up to read just one more chapter until long past when you needed to go to sleep. Whose writing can thrill you and chill you — and all at the same time make you think about what salvation ought to look like in the modern American South.

I’m Chuck Reece, and welcome to Salvation South Deluxe, a series of in-depth episodes that we add to our regular podcast feed — hoping to unravel the untold stories of the Southern experience by letting you hear the authentic voices that make this region truly unique.

THEME MUSIC UP

ACT ONE

Chuck Reece: David Joy can tell us how the word “noir” first got coupled with Southern fiction.

Chuck (from interview): When did you first hear the term “Southern noir”?

David Joy: Well, to be honest, that term wasn't being used when I — when I started publishing, really. It hadn't become the thing that it is now. The first time that I ever encountered it … Daniel Woodrell had a novel called Give Us a Kiss, and it was originally titled Give Us a Kiss: A Country Noir. ... In a lot of ways, that's kind of the genesis of that term being used in that regard.

Chuck Reece: Daniel Woodrell is from the Ozark Mountains. If you talk to any writer about the moodiness of film noir being deployed in rural places, Woodrell’s name nearly always comes up. His most famous novel is from 2006. It’s called Winter’s Bone. In 2010, Winter’s Bone was made into an Oscar-nominated film, which you might remember, because it provided the first starring role for one of Hollywood’s biggest icons, Jennifer Lawrence.

John Hawkes, from Winter’s Bone: You know your daddy’s out on bond, don’t ya? His court date’s next week and I can’t seem to turn him up.

Jennifer Lawrence: I’ll find him.

John Hawkes, from Winter’s Bone: Girl, I been lookin’.

Jennifer Lawrence: I said I’ll find him.

Chuck Reece: Woodrell’s work was one of David Joy’s early inspirations. But not his earliest.

David Joy: My mother will say that I was — I was writing stories before I could spell, which is kind of a romantic story, but it's true. She was a potter. And she set on one end of the couch and she'd be working with clay, and there was a table beside that couch and it had an old typewriter under it. And I'd pull that typewriter out at night and I'd tell her stories and she'd tell me how to spell the words. And I mean, I have very vivid memories of that. … Even as a tiny kid, I wrote books, and I took them around the neighborhood and sold them to try to get money to buy stuff.

Chuck Reece: But when he enrolled at Western North Carolina University, he was lucky enough to wind up under the wing of Ron Rash, who teaches creative writing at WCU and is arguably the absolute master of Appalachian fiction.

David Joy: When I got to college, I didn't know what I wanted to do, other than that I knew I wanted to write. I didn't know what that looked like. I didn't know that you could even study, you know, creative writing. But one of those teachers, she just dropped me in Ron Rash's lap. Not as a student, initially, just as someone who was writing, and she was like, “You need to meet this person.” And Ron was who handed me, you know, so many of those books early on.

Chuck Reece: Ron Rash, who celebrated his 70th birthday not long ago, for years has run the creative writing program at Western Carolina [University]. No one disputes that Rash is one of the greatest living Southern authors. Since 1994, Rash has published seven short-story collections, five books of poetry, and eight novels — all of which have a masterful grasp of the people, the ways, and the land of the Appalachian Mountains.

One of the books Ron Rash gave to a young David Joy changed his life.

David Joy: It was William Gay's I Hate to See That Evening Sun Go Down. And that was the very first time that I had ever encountered my people on the page. You know, it was places that I knew. The sound of it was what I knew. And up until that moment, I didn't — I didn't know that you could write literature about those people. You know, I think for a lot of young writers, there's kind of an identity crisis, especially if you come from a group that historically is not represented in the canon.

Chuck Reece: So David’s goal became to write books with characters who were familiar to him. But when David started sending his first novel, Where All Light Tends to Go, to publishers, he took a cue from that Daniel Woodrell book.

David Joy: When I think about that very first novel that I ever wrote, I wrote that novel because there wasn't another Daniel Woodrell novel to read. And I wanted one. ... And when it came time to try and pitch that book, I just invented the term “Appalachian Noir.” I'd never encountered that term. But in my mind, that's what it was.

I think at the heart of it, for me ... is the idea of mood. You know, it's the idea of kind of this overshadowing mood over the entire work.

Chuck Reece: The dark moodiness David talks about is shared territory with the writers whose pens gave birth to film noir back in the 20th century. One leading writer of that movement was James M. Cain, whose novels included Double Indemnity, Mildred Pierce, and The Postman Always Rings Twice — all of which were turned into Hollywood film noir hits. The other was Dashiell Hammett, whose books The Maltese Falcon and The Thin Man were the source material for more film noir classics.

But Cain’s and Hammett’s characters mostly lived in California, in L.A. and San Fransicco. Hammett’s Sam Spade and Cain’s Mildred Pierce were urbane characters. They hung out in nightspots where the martinis were always perfectly stirred, crystal clear and cold.

The characters David Joy wanted to write were not urbane. Not in the least. They were people like Dwayne Brewer, from David’s third novel, The Line That Held Us. Here is the first sentence of that book’s second chapter.

Dwayne Brewer goose-stepped down the beer aisle of the Franklin Walmart wearing a chimp mask he’d found on the floor by the Halloween decorations.

David Joy: I like the idea of the rough South. You know, I like the idea of writing about hardscrabble lives ... who are doing the best that they can with what they have.

Chuck Reece: That term — hardscrabble — is apt to make me think of rural places, but you’d be mistaken to think the term is that narrow. Too many people in Southern cities live hardscrabble lives. And without a doubt, no writer whose work might be labeled Southern noir has sold more books or made bigger waves in the literary world than Atlanta’s Tayari Jones.

Her first novel, Leaving Atlanta, from 2002, tells the stories of three fifth-grade students growing up during the Atlanta Child Murders — a string of 28 killings of young African Americans from 1979 to '81. Jones herself was a fifth-grader in that period, growing up in the SWATS — or Southwest Atlanta.

Tayari Jones: I grew up in all-Black Atlanta. I grew up in Southwest Atlanta, where everyone was Black. I knew that, theoretically, Black people were a minority in America. I knew it, but I didn't believe it. I sometimes say it's like when you know that the Earth is 80% water. You know it, but you don't believe it.

Chuck Reece: And her formative years coincided with events that shocked her world to its foundations.

Tayari Jones: When I would tell people I grew up in the Child Murders, they would say, “My God, your mother must have been so terrified.” And there had really been nothing from the point of view of my generation, and we're the ones that it really happened to. Adults understood the Child Murders in the context of history. Children do not have an understanding of history that’s their own. They're in the moment. They’re having a completely different experience.

Chuck Reece: A small publishing house in New York City called Akashic Press in 2004 published a collection of short stories called Brooklyn Noir. The series — collections of noir-ish short stories set in specific locations — now includes more than 90 volumes. Tayari Jones served as editor of Atlanta Noir, which came out in ‘17.

In her introduction to that collection, she wrote, and I quote,

When we write noir, we don’t shine a light into darkness, we lower the shades. There are no secrets like Southern secrets and no lies like Southern lies.

Tayari Jones: I do think that Atlanta lends itself to noir because Atlanta has such a public reputation. You know, we are "the city too busy to hate." We are the New South. We are a chocolate city, all these kinds of things. And so we have a propaganda machine as to how awesome we are — which lends itself to lies.

Chuck Reece: If Tayari Jones meant to, as she wrote in her Atlanta Noir editor’s note, “expose the rot underneath the scent of magnolia and pine,” she certainly did so in her novel that came out the following year — An American Marriage.

An American Marriage tells the story of a young Black couple in Atlanta. Celestial, an artist and daughter of college-educated parents who grew up in the city, and Roy, who grew up in rural Louisiana, are newlyweds. Early in their marriage, they visit Roy’s hometown, and Roy is falsely accused — and later convicted — of raping a white woman.

The novel shot Jones to the top of the bestseller lists after Oprah Winfrey made the book a pick of her book club.

On the level of pure suspense, the book revolves around the question of whether Celestial and Roy’s marriage will survive while he is in prison and appealing his conviction. But on a deeper level, the book is a hard and personal look at mass incarceration in America, and the prejudice Black people experience in the justice system.

Unlike the noir novels of James M. Cain and Dashiell Hammett — or the modern bestselling detective novels of writers like Lee Child and Michael Connelly — An American Marriage does not set the situation back to rights. Because when someone is wrongfully imprisoned, the situation can never be set right.

Tayari Jones: This is why I don't think An American Marriage fits as a thriller, because at the end of the thriller, the problem is solved. Things are put back in their proper place.

Chuck Reece (from interview): Yes.

And I feel like at the end of An American Marriage, things are put in a new place.

Sometimes when you have a novel where there is some sort of overt kind of societal issue like wrongful imprisonment, there is an urge to write the characters almost as though they know you're watching them, so they're on their best behavior.

Chuck Reece: But to do so in that book, Jones says…

Tayari Jones: It would have been dishonest and trivializing of a problem, if you end it where the people are back on track and it's as though the wrongful imprisonment never happened. There are consequences to this incarceration. … Even when you get out, you can't be given your time back. Once you have been accused of a crime, your innocence is always a matter of debate.

So in An American Marriage” we have this young couple, you know, who've done I'm not going to say everything right … but they've done most things right. They've done most things right, and nothing certainly that's outside the law. And, you know, the husband is arrested for a crime he did not commit, and that is the greatest fear, right? Like, it's almost like incarceration was the boogeyman under the bed and jumped out and attacked them.

I’m not even just going to say Southern, but we're going to talk about Southern writers now, but I do think that the African American writers’ relationship with home, with the South, it has that tension between being both inside tradition but also there's a sense of always being an outsider and the threat of the law.

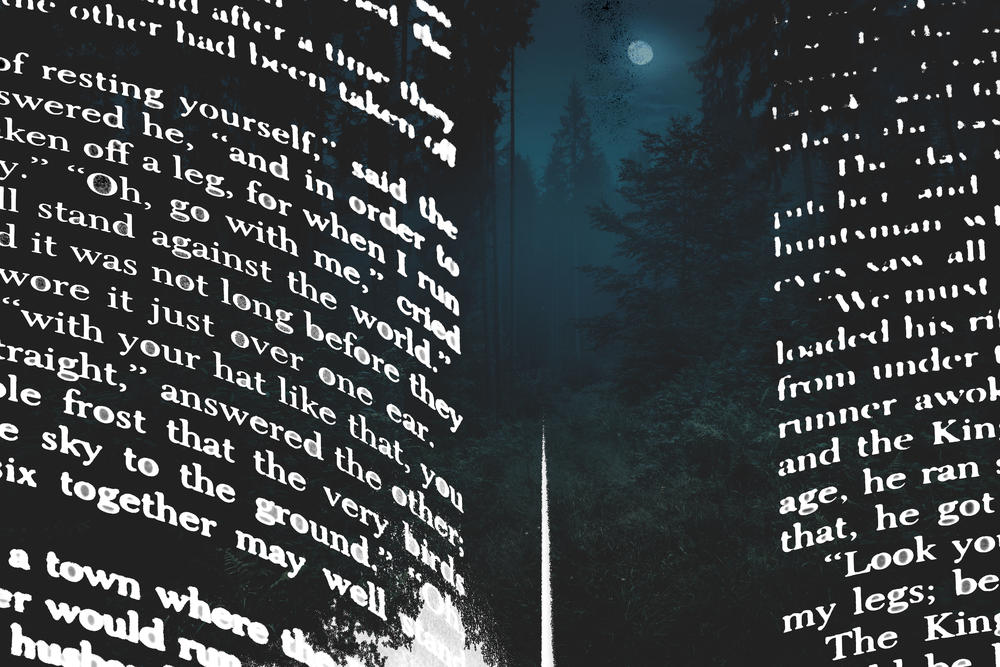

Chuck Reece: The novels of Michael Farris Smith look hard at how characters on the fringe of Southern society, by virtue of class or economic circumstances, are forced to interact with the justice system.

Michael Farris Smith: We all have a relationship with the law, every one of us. And it's dependent on what we look like and where we're from and what socioeconomic background we are from.

Unless you're middle to upper class white…you're looked at differently by the law. If you're on the fringe, if you are lower on a socioeconomic ladder, whatever you do could be exactly as someone who is upper middle class could also do, and you will be treated very differently by the exact same law enforcement officer.

Chuck Reece: At the beginning of this show, I read you the first sentence of Desperation Road, the first novel of Smith’s I ever read. It begins with a young, white, homeless, single mother named Maben Jones, walking down the shoulder of an interstate highway in Mississippi. She’s carrying a plastic garbage bag, and her daughter walks along behind her.

Michael Farris Smith: When I write about the law…I'm not interested in procedure or any of that. I'm not interested in what the cops are talking about in their office, trying to figure out who done it. I'm really interested in Maben and her little girl walking down the side of the interstate. A man picks them up, takes them to the Fernwood Truck Stop. She's walking across the parking lot in the middle of the night where some other girls are going up in the trucks as prostitutes. And the cop pulls in and sees her and immediately assumes, by taking one look at her, she's a prostitute, and throws her in the back of the car.

Chuck Reece: Like Jones, Smith is not interested in telling readers how they should think about a particular social issue. He wants to put his readers inside situations where characters have to face those issues. It’s not a lecture. It’s an invitation to empathize.

Michael Farris Smith: I am not interested in preaching to anybody. … I can feel it when I'm reading a novel and I feel like the somebody's trying to really make me understand something, and I don't like that. Maybe it's because I grew up being a preacher's kid. I got that three times a week, formally, and a lot more informally the rest of the week. That's something else altogether. But I think to be able to present an idea or a theme or a feeling or a mood or emotion or attitude in a in a way that's engaging. In fiction, you got to create that world.

Chuck Reece: In his most recent novel, Salvage This World, Smith created a world of the future, in southern Mississippi, where he grew up near the Gulf Coast. He fast forwards readers to a time when, thanks to climate change, hurricane season on the Gulf of Mexico doesn’t just run from June through November. It just keeps going, year-round.

The only people left living there are folks who were too poor to leave and move northward — and the grifters who are looking to prey upon those poor people.

Over the last decade, I’ve read many books that bookstores might put on a shelf labeled “Southern noir.” The common element in all the good ones, it seems to me, is how they stick up for Southerners who have been disenfranchised in one way or another. It might be by race. Or by poverty. Or by addiction.

A hundred years ago, Southern literature put a glossy sheen on our region’s ugly truths. The example that looms largest — and lingered longest — is Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind.

But in this century, the writers of Southern noir are up to something very different. They work hard, as Jones put it, to expose the rot under the magnolia blossoms.

Salvation South Deluxe will be back right after this break.

MIDROLL BREAK

ACT TWO

Chuck Reece: If there is a common element among all the authors we’ve talked so far, it’s a desire to create characters who have been “othered,” so to speak. People that society puts on lower rungs of the ladder. Folks that Michael’s preacher father might have called “the least of these.”

David Joy told us earlier how he was driven to write characters who felt like the people he knew as he grew up in Appalachia. Chris Offutt, a writer who’s a generation older than Joy, knows what that feels like.

Over a 30-year-plus literary career, Chris Offutt has written a little of everything.

Chris Offutt: I've written nonfiction, books of short stories, novels, this crime series. So I'm — I’m like a smorgasbord for a reader.

Chuck Reece: He left out the fact that he’s written for television, too, having authored episodes of Weeds, the darkly comic Showtime series about a suburban mom who is also a weed dealer, plus two HBO shows that were set in the South: True Blood, a very noir-ish drama about vampires in rural Louisiana, and Treme, which was set in New Orleans during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

John Goodman, from Treme: Day by day, year by year, New Orleans also conjures moments of artistic clarity and urban transcendence that are the best that Americans as a people can hope for.

Chuck Reece: Offutt grew up in Rowan County, Kentucky, next to the Daniel Boone National Forest in the northeastern part of the state.

Chris Offutt: I grew up in the woods. It's way back in the woods. It was a mining town, a clay-mining town.

Chuck Reece: If you think of Eastern Kentucky as coal-mining country, you’re right. But coal wasn’t all that the 20th-century barons of industry paid poor people to extract from those mountains.

Chris Offutt: Under those lumps of land, the hills, there's caves, coal, clay and a little bit of natural gas. And where I grew up happened to be this yellow clay that made … fire bricks. And they would use those fire bricks to make the big kilns [in Ohio and Michigan and wherever they, you know, needed kilns]. But by the time I came along, I was just down to 200 people and a lot of empty holes in the ground. A hell of a lot of broken bricks and real yellowy thick mud when it rains.

Chuck Reece: Since 2021, Offutt has been writing a series of thrillers built around the same character: Mick Hardin, a U.S. Army Criminal Investigations Division officer who has come home to the small Kentucky town in which he grew up. Three Mick Hardin novels — The Killing Hills, Shifty’s Boys, and Code of the Hills — have been published. The fourth in the series, The Reluctant Sheriff, is due out in 2025.

One critic called the Hardin series “an accomplished addition to the ranks of country noir.” But Offutt himself cares far less about the categorization of his work than what the characters he writes represent.

Chris Offutt: Everything I write is set in the hills of Kentucky, where I grew up. Either they start there, and sometimes the character will leave and return. Or sometimes leave and just miss it horribly. ... That would sum up how I approach writing.

I love film and movies and photography. I always thought of the word the term noir as the French term for black and white movies shot in the '40s and '50s, low budget in Hollywood. Then somehow it made that jump into being all kinds of stuff that's called noir. So I'm not even sure what noir means anymore.

These categories that are invented have nothing to do with the writer. They benefit bookstores so they can put in these sections. They love to section 'em up. They really benefit libraries for the same reason. And in some ways, they may benefit a person browsing for a book, but they don't have anything to do with the writer. I don't set out to write anything other than what I do, and then somebody else will call it or label it.

Chuck Reece: What Offutt writes, he will tell you, emphatically, is for and about the people of the hills and hollers of where he grew up. People from the mining country of eastern Kentucky have long fought against wealthy barons of industry who have arrived to extract riches from their land. First, they cut down the old-growth forests for their timber. And when that was gone, they cut off the mountaintops to get to the coal underneath. People from mining country have been disenfranchised since forever.

So Chris Offutt is not writing crime fiction or Southern noir or whatever you want to call it because he’s being loyal to a genre. He’s doing it because crime is a part of his native landscape.

Chris Offutt: As a true man of the hills, I don't think that illegal activity necessarily makes somebody criminal.

Chuck Reece (from interview): That's right.

Chris Offutt: It just means that they made laws to protect the rich people.

Chuck Reece: But when the pandemic came in 2020, Offutt, stuck in Mississippi where he lived at the time, teaching creative writing at Ole Miss, did set out to write a straight-up crime novel. That was the beginning of his Mick Hardin series.

Chris Offutt: I thought I'd set out and write this book, and I finished it in eight months. I'd never written a book that fast because there was there was nothing else to do. And after eight months, you know, I worked on it and then I missed those characters, Mick and Johnny Boy and Linda. I realized I'd spent more time with these imaginary people than any other actual living person. And I missed them. And so I thought, “Well, I'll write another one.”

It was not — it was accidental. It was not deliberate. It was not intentional. I never set out to write a series. I never had that as a goal or ambition.

Chuck Reece: But it began to feel important to him to write the stories of these characters he’d created for the series — men and women of the hills, like himself.

Chris Offutt: It's important because so little is known about people who fall into this, these groups, these disenfranchised groups, and they're all over the country. They become maligned, they become blamed, they become a butt of jokes, and that becomes what people think is true. It slides off into stereotype.

When there's books written about these people with compassion, generosity and understanding, it goes a long way towards showing the out —the external readers, you know, people who live in the suburbs and live in the cities and are, you know, middle class and above, it brings insight to them about — about people that they just don't know anything about. That can lead to just ... I think, improving society by altering the way people — strangers — would view a group of people who are maligned simply because they are disenfranchised and have no voice.

Chuck Reece: While “Southern noir” is indeed a handy term for those whose business is to sell books — or to introduce them to readers in libraries — it might be more accurate to call this the Literature of the Disenfranchised. Or the Voices of the Southern Voiceless.

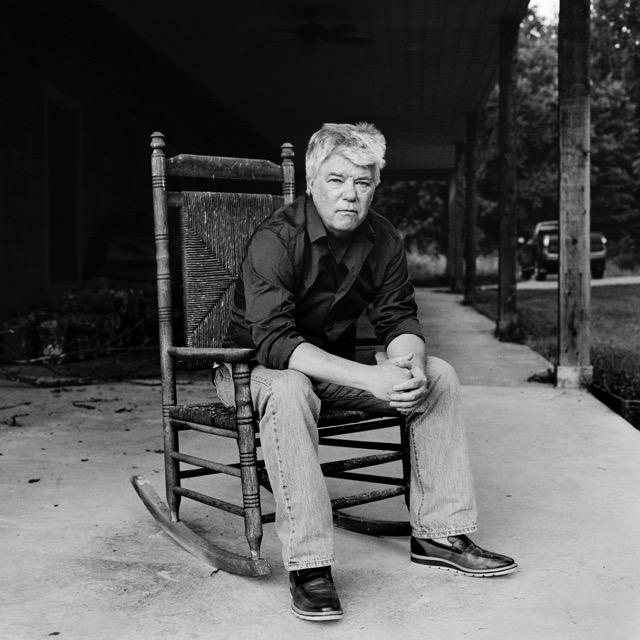

The Virginia writer S.A. Cosby, I think, would agree with that. S.A. — he goes by Shawn — grew up in Virginia, on the Chesapeake Bay.

S.A. Cosby: I come from a little small place called Matthews, Virginia, population 8,000. I know all of them, and I'm related to half of them.

Chuck Reece: What was that work David Joy used? Hardscrabble? That fits Shawn Cosby’s upbringing.

S.A. Cosby: We were very poor growing up. I'm 51 and I didn't have running water until I was 16. But I never felt... I knew we were poor, but I never felt impoverished.

Chuck Reece: His hometown of Matthews is on Mobjack Bay, a small inlet that is part of the massive Chesapeake Bay ecosystem.

S.A. Cosby: I learned to swim in Mobjack Bay. There used to be a tree with a rope. Nobody knows who tied the rope. But many a kid learn to swim in Matthews by grabbing that rope and swinging out into the bay. It's sort of this bucolic childhood that I had. It was so beautiful growing up in a small town like that.

Chuck Reece: When Shawn was young, three of the most important women in his life — his mom, aunt and grandmother — were big readers. But neither they nor he encountered characters in novels whose lives reflected their own — poor, Black, making their livings off the sea.

S.A. Cosby: Fishing culture was huge in Matthews as a kid. My dad was a fisherman, a commercial fisherman for about 40 years. So they would go off of the Mobjack Bay. They would cast off from there and they would go crabbin’. Crab pots. They would do oyster, you know, those big tongs to drag oysters off the bed of the of the river.

My mom and dad separated. You know, I just learned to appreciate the land. My grandfather grew a garden. He kept a couple of pigs.

Chuck Reece: Shawn’s second novel, Blacktop Wasteland, catapulted him onto the bestseller lists in 2020, but before that worked mostly with his wife, who owns and runs a funeral home. His 2024 novel, All the Sinners Bleed, hit the New York Times and USA Today bestseller lists immediately after it was released, and former President Barack Obama added it to the summer reading list he publishes every year.

All the Sinners Bleed follows the story of Titus Crown, a former FBI agent who has moved home to take care of his father in rural Virginia and has become the county’s first Black sheriff.

S.A. Cosby: I think the crime novel — I like to say, and I've said this before, the crime novel is like the gospel of the dispossessed.

Everybody knows about bitterness and jealousy, and so crime novels, in their sort of inimitable way, are able to articulate those feelings, in addition to giving you suspense, in addition to giving you thrills.

Chuck Reece: Cosby’s amazing skills at spinning thrilling and suspenseful tales are always coupled with his willingness to take on issues that not all Southerners are comfortable with.

His third book, Razorblade Tears, tells the story of two former convicts, Ike Randolph and Buddy Lee Jenkins, whose sons, Isaiah and Derek, are married.

Cosby remembers pitching the book to his publishers during the pandemic, after the success of Blacktop Wasteland.

S.A. Cosby: That book was funny because I had written Blacktop Wasteland, and at the time, I had a Zoom — you know, we were still in lockdown — so I had a Zoom meeting with the publisher like the following, that fall. And they're like, “So what do you come up with next? What do you want to do? You want to do a sequel to Blacktop?” — which I do, one day.

And I said, “Well, I got this idea.”

“Oh, please tell us. Tell us.”

And I said, “All right, these two fathers, one black, one white, both ex cons who are homophobic, avenge the murders of their gay sons who they ignored and disdained in life.”And nobody said nothing for a minute. And it’s like, “All right…”

Chuck Reece: But when it came out in July of ‘21, Razorblade Tears debuted on the bestseller lists and sparked a bidding war among movie producers.

S.A. Cosby: My writing up to this point has always been about confronting issues of race and class and religion and sexuality. And you know, I think as writers, you have a duty to talk about that.

Chuck Reece: But his duty, Cosby is quick to point out, isn’t to lecture anyone about any of those topics. His duty, he says, is to tell those stories because in the South, his home, those stories play out in uniquely Southern ways.

S.A. Cosby: I think there's something unique within the Southern experience about history and lore and legend and how storytelling is so intrinsic to our understanding of each other. Some of the greatest stories I ever heard was sitting around, you know, an outside grill listen to my uncles and my grandfather and my dad and folks and my aunts and my grandmother tell stories, you know? And again, like they say, I don't know. I think they say this in the South: "If it wasn't true, it should have been." And so that experience being around these backyard raconteurs, these, you know, barbecue orchards, really, I know it had an influence on my own writing.

As a Southerner, I think our writing has a unique place in the in the, you know, the American pantheon of letters. You think about William Faulkner, but you also got to think about Flannery O'Connor. You think about Ernest J. Gaines. You think about Alice Walker. You think about all the great Southern scribes who struggle with and sort of illuminate what it means to be from this place below the Mason-Dixon of, you know, red clay and and blues and gospel. But there's a thing in music, whether it's the blues or whether it's rockabilly that I call the camaraderie of poverty?

Chuck (from interview): That's a beautiful phrase, man.

S.A. Cosby: Man, thanks. But I came up with that because I listened to and someone talk about “Blue Suede Shoes.”

MUSIC: Carl Perkins - Blue Suede Shoes

“Now don’t you step on my blue suede shoes.”

S.A. Cosby: A lot of people just hear it in as a, you know, it's a catchy beat. It's a catchy song, but when you dig into those lyrics, it really speaking about a man or a person who's poor and the only thing they got is like an expensive pair of blue suede shoes. So when he says, "Don't step on my blue suede shoes, it's not just saying, "Hey man, don't step in my shoes," it's like, "Don't, don't crush this thing that I have this this thing that gives me a sense of worth, a sense of self."

Chuck Reece: The camaraderie of poverty. That phrase reminded me of my conversation with David Joy, when he equated the poverty in which many of his characters live with violence.

David Joy: When you're writing about these types of class issues, when you're writing about addiction, which is oftentimes a class issue, when you're writing about crime, which is most often tied to class issues, you know, those are things that are inherently violent.

Chuck Reece: Perhaps that is why the stories contained in Southern noir — or crime fiction, or whatever we choose to call it — are so often propelled forward by acts of violence. Here’s David Joy again.

David Joy: But I think that to write an American novel that — that was not inherently violent would be disingenuous. Which is to say that every institution of power that exists in this country is inherently violent. Capitalism is inherently violent. You know, it might not be gun-to-your-head violence, but, you know, having to scrounge up a meal to keep from starving, having to sleep in your car, you know, to keep from drowning is — is a form of violence.

Chuck Reece: I think Shawn Cosby might have nailed that idea perfectly in All the Sinners Bleed. The book opens with a short chapter that sets the scene in the fictional Virginia county called Charon, where Titus Crane has just become the first Black sheriff.

I want to read a bit of that chapter to you:

Blood and tears. Violence and mayhem. Love and hate. These were the rocks upon which the South was built. They were the foundation upon which Charon County stood. If you had an occasion to ask some of the citizens of Charon, most of them would tell you those things were in the past. That they had been washed away by the river of time that flows ever forward. They might even say those things should be forgotten and left to the ages.

But if you had asked Sheriff Titus Crown, he would have said that anyone who believed that was a fool or a liar. Or both. … He might touch the scars on his face or his chest absentmindedly and lock eyes with you and say in that harsh whisper that was now his speaking voice: “The South doesn’t change. You can try to hide the past, but it comes back in ways worse than the way it was before. Terrible ways.” He might sigh and look away and say: “The South doesn’t change … just the names and the dates and the faces. And sometimes even those don’t change, not really. Sometimes it’s the same day and the same faces waiting for you when you close your eyes.

Waiting for you in the dark…

Chuck Reece: What a rare privilege it was to have these conversations with such amazing writers. I want to thank Tayari Jones in Atlanta, Shawn Cosby in Gloucester, Virginia, Michael Farris Smith in Oxford, Mississippi, Chris Offutt, who has just moved from Oxford to Iowa City, and David Joy, who lives on a mountain up above the Tuckasegee River in western North Carolina. Without them generously sharing their time, we could not have produced this episode.

I also must thank my friend Frank Reiss, different spelling but my brother nonetheless, for turning me on to this stuff in the first place.

And if we’ve interested you in reading these writers, check the show notes for this episode, where we’ve placed a list of their works — and other books they mentioned during the episode.

You’ve been listening to Salvation South Deluxe, proudly produced in cooperation with Georgia Public Broadcasting and its network of twenty stations around our state. Every Friday, we add a new three-minute commentary about Southern stuff to our podcast feed, and every month or so, we add longer, dee-luxe stories, such as the one we’ve just told you.

I’m Chuck Reece, your host and the editor-in-chief of Salvation South, which you can find 24/7 at SalvationSouth.com

Our producer is the talented Jake Cook, who also composed our theme music. GPB’s director of podcasts is Jeremy Powell, and none of this could have happened without wonderful people like GPB’s Sandy Malcolm and Adam Woodlief.

We’ll be back next month with another full-length episode of the Salvation South podcast.

✦✧✦✧✦✧✦✧✦✧

Southern fiction reading list:

- My Darkest Prayer—2019

- Blacktop Wasteland—2020

- Razorblade Tears—2021

- All the Sinners Bleed—2023

- Leaving Atlanta—2002

- The Untelling—2005

- Silver Sparrow—2011

- Atlanta Noir (editor and contributor)—2017

- An American Marriage—2018

- Where All Light Tends to Go—2015

- The Weight of This World—2017

- The Line That Held Us—2018

- When These Mountains Burn—2020

- Those We Thought We Knew—2023

- Kentucky Straight—1992

- The Same River Twice: A Memoir—1993

- The Good Brother—1997

- Two-Eleven All Around—1998

- Out of the Woods—1999

- No Heroes: A Memoir of Coming Home—2002

- My Father, the Pornographer: A Memoir—2015

- Country Dark—2018

- The Killing Hills—2021

- Shifty's Boys—2022

- Code of the Hills—2023

- The Hands of Strangers—2011

- Rivers—2013

- Desperation Road—2017

- The Fighter—20128

- Blackwood—2020

- Nick—2021

- Salvage This World—2023

Other books mentioned in this episode

- Give Us a Kiss: A Country Noir, by Daniel Woodrell—1996

- Tomato Red, by Daniel Woodrell—1998

- Winter’s Bone, by Daniel Woodrell—2006

- I Hate to See That Evening Sun Go Down, by William Gay—2002

Salvation South editor Chuck Reece comments on Southern culture and values in a weekly segment that airs Fridays at 7:45 a.m. during Morning Edition and 4:44 p.m. during All Things Considered on GPB Radio. You can also find them here at GPB.org/Salvation-South.