Section Branding

Header Content

'Time of the Child' is a marvelous blend of despair and redemption

Primary Content

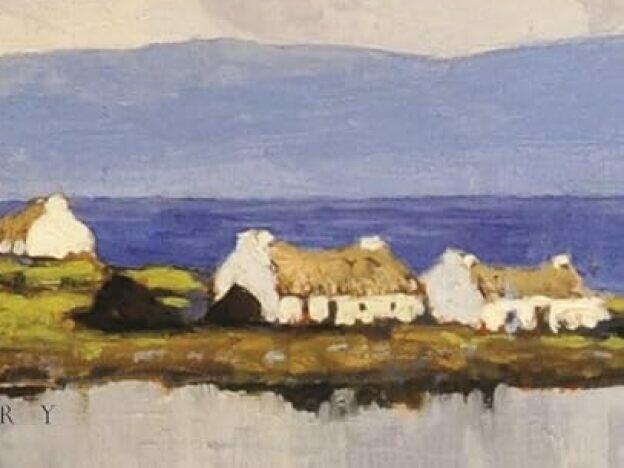

A village "on the western edge of a wet nowhere" populated by men who drink too much and women who smile too little. Throw in cows, an addled priest, an abandoned baby and a thick cloud cover of shame and you have the elements for a quintessential Irish story.

So quintessential, in fact, I've held off reading Niall Williams for a long time, despite hearing raves about his work. My skepticism, it turns out, was misplaced. I've just emerged from a Niall Williams binge with a belated appreciation for his writing, which invests specificity and life in characters and places easily reduced to clichés.

Time of the Child is Williams' latest novel, a companion piece, rather than a sequel to, his 2019 novel, This Is Happiness. Both books are set in the rural village of Faha — a town in the far west of Ireland whose inhabitants, we're told, possess "the translucent flesh that came from living in an absolute humidity."

Time of the Child takes place in the weeks leading up to Christmas 1962 and opens — and closes — on a set piece of Mass at the parish church, where most of the village gathers. In between lies a story that feels, at once, realistic in its rough and comic everyday unfolding and mythic in its riffs on the grand themes of despair and spiritual redemption.

Jack Troy is the town doctor and central character here. He's a melancholy contained man who, we're told, "carrie[s] himself in a manner that [the townspeople of] Faha might have summarized as Not like us." Dr. Troy lost his wife and then the older woman he unexpectedly fell in love with, who's now also dead. Keeping house for him is his 29-year-old daughter, Ronnie, the eldest of three sisters; the one who remained at home.

Ronnie, too, is a semi-enigma to the townspeople: Our narrator tells us that "Added to [her] reserve was not only the screened lives of all women in the parish at the time, but the marginal natures of all writers, for Ronnie Troy's closest companion was her notebook."

Dr. Troy has become haunted by despair and by a particularly heartrending question: "Why does no one love my daughter?" The answer, he fears, is his own glowering presence that may have repelled one especially promising suitor.

Inspired by what we're told is a "mixed fuel of ... brandy ... [and] a parent's fear of the unmade world after them," Dr. Troy, uncharacteristically, resolves on a bizarre scheme to make things right. As the saying goes: "Man plans, God laughs."

Instead of unfolding the Troy family narrative chronologically, Williams layers it on top of other simultaneous storylines, all of which are graced with language as bracing as salt spray from the chill Atlantic. We follow, for instance, the wanderings of Jude Quinlan, a 12 year old "on the rope-bridge between man and boy."

Jude's father drinks and gambles and his mother, Mamie, possesses "the anxious look of one married to an instability." Listen to how Williams moves fluidly from the mundane to the wider lens of the numinous in these snippets from an extended passage where Jude helps to unload a van full of Christmas toys for the town fair:

There were toy soldiers, kits for flying gliders, ... skittles in a net, balls, bats. ... dolls of one expression but many dresses, ...

For Jude, carrying everything from the van ... was as close has he would get to handling any of these things. He had no resentment or bitterness . Rather, from nearness to the marvelous something rubbed off on him ...

The other thing, the one that only occurred to him years later when he would recall what happened that day, was that what he was carrying out of the van that December morning was his childhood.

For those who believe in such phenomena, Jude will be the instrument for bringing a miracle — a Christmas miracle complete with a baby and a virginal mother, no less — into this story. The other miracle here is a literary one: Time of the Child itself, which gives readers that singular experience of nearness to the marvelous.