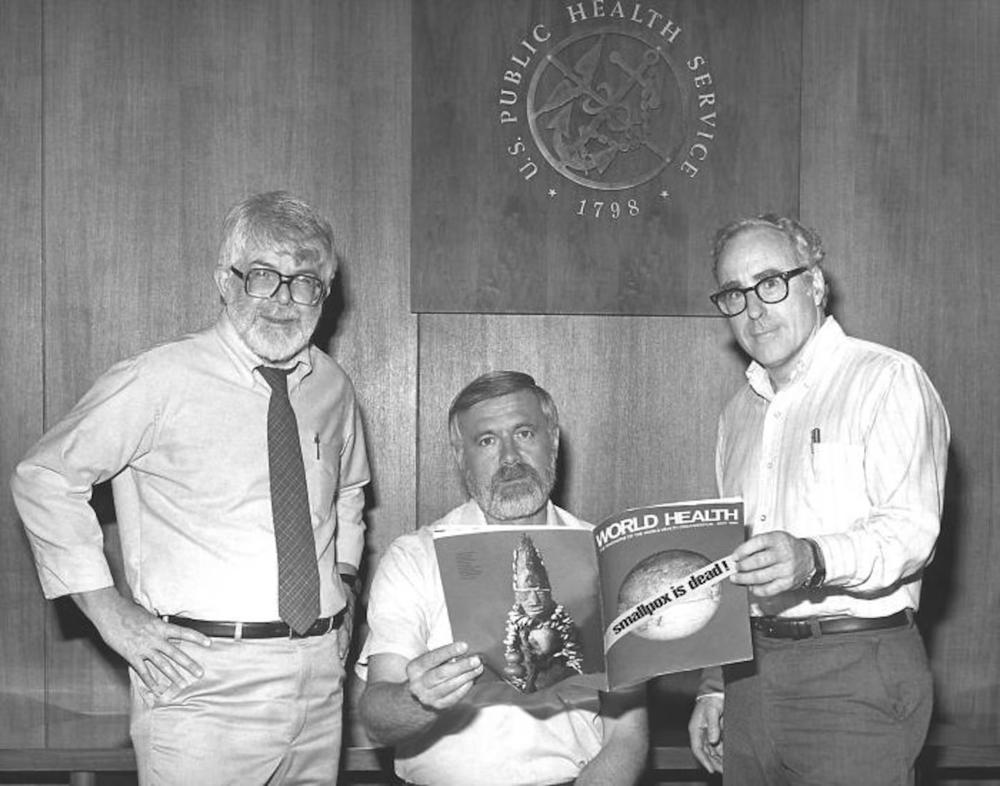

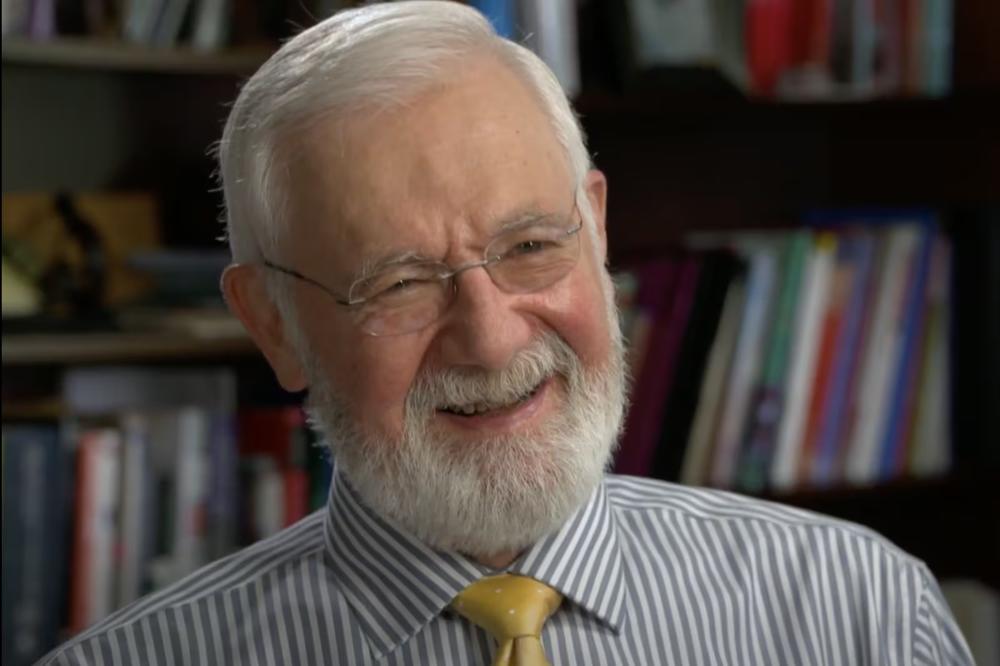

Caption

Dr. Bill Foege is among the leaders credited with helping eradicate smallpox in the 1970s. He served as Centers for Disease Control director in the Carter administration and went on to launch the Task Force for Global Public Health in Decatur, Ga.

Credit: Task Force for Global Public Health