Caption

A road block stands near the site of two positive avian influenza cases in Elbert County, Ga.

Credit: Chase McGee/GPB News

LISTEN: The U.S. is in the second year of a nationwide, multi-species outbreak of H5N1, the highly pathogenic avian influenza some call bird flu. Georgia has been able to stay ahead of it until recently. As GPB's Chase McGee and Sofi Gratas explain, that’s because the state has a longstanding system for disease prevention and response.

A road block stands near the site of two positive avian influenza cases in Elbert County, Ga.

The United States is in the second year of a nationwide, multi-species outbreak of H5N1, the highly pathogenic avian influenza some call bird flu.

Georgia has been able to stay ahead of it until recently. A case of bird flu shut down an operation growing chickens for the dinner table in Elbert County earlier this month. Just before that, there was a positive reported case in a backyard flock in Clayton County just south of Atlanta.

The second case in Elbert County represents the third commercial flock where avian influenza has been detected in Georgia since 2022, and the sixth total case in that same time frame.

State officials and scientists credit the small number of cases so far to Georgia’s longstanding system for disease prevention and response, set up to protect the state's billion-dollar poultry and egg industry.

State Veterinarian Janemarie Hennebelle has been on the front lines of the outbreak in Georgia and helps in positive case mitigation — the first step of which is a speedy response.

Shortly after the Elbert County case was confirmed, backroads leading into the infected chicken houses were blocked. Old, sun-bleached biosecurity signs warn unauthorized people to stay out of farms on the way to ground zero.

“We want to get out there immediately so that we limit the suffering of those birds,” Hennebelle said. “It is very unpleasant for the chickens that are affected.”

Arriving quickly is crucial and humane as avian influenza, which causes neurological damage, is highly contagious. All it takes is one infected chicken for the virus to spread and wipe out a whole chicken house.

Hennebelle says any chicken producer with a positive case has to cull their entire flock all at once. Culled birds can’t be sold or eaten, either. In Elbert County, that meant killing over 100,000 chickens over the weekend of Jan. 17.

“To go through that, to see that on your own farm with your own birds, it's very difficult,” Hennebelle said. But to do otherwise risks the collapse of a major part of the food system.

“I have to think about the entire population of chickens in the state of Georgia, all of our neighbors and across the country,” Henebelle said. “We are trying to protect human health and we are certainly actively protecting the food supply.

That work takes thousands of people: scientists, policy makers, plus farmers big and small. And warnings over further spread of avian influenza have only gotten louder. Over the past year, the virus has mutated and spread into previously unimaginable species, including cows, domestic cats and humans.

Meanwhile, stakeholders who have spoken with GPB say they’re confident in the state's ability to respond to this widespread outbreak.

Chickens are Georgia’s No. 1 farm product; eggs are its second. The state leads in the country for broiler production — chicken raised for meat.

According to the Georgia Department of Agriculture poultry makes up 35% of Georgia's agricultural economy.

A truck filled with broiler chickens, bred to be consumed, heads toward the Pilgrim's Pride meat processor plant in Athens, Ga., on Jan. 29, 2025.

To protect this industry, chicken and egg farms are expected to use biosecurity. Essentially, steps to eliminate virus spread that started in wild bird populations.

The Department of Agriculture does not mandate biosecurity but spokesperson Matthew Agvent called it “essential” and said that the department has been encouraging all livestock farmers to enforce it.

“At the end of the day, farmers obviously have a significant financial incentive to keep animals safe,” Agvent said.

At the basic level, biosecurity includes keeping tabs on who is in contact with a chicken flock, and making sure they’re sanitizing themselves and equipment before every interaction. Biosecurity can also mean eliminating contact from outside sources completely, as well as avoiding any movement of animals like through trade or free ranging.

David Suarez, research lead of the Exotic and Emerging Avian Viral Disease lab in the U.S. National Poultry Research Center in Athens, said maintaining biosecurity in the age of bird flu can require a big effort. But it has paid off.

Spread of avian influenza was once far more common between farms. Enhanced biosecurity and testing has reduced such spread.

“We're doing a much better job of having that rapid identification and rapid response, and we're seeing much less farm-to-farm spread,” Suarez said.

Now, there’s more of a focus on prevention of spread from wild birds, including ducks, geese and swans. The virus can pass from their excrement and saliva, like what’s left over on food.

“The influenza virus is certainly opportunistic,” said Alex Turner, incident coordinator with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. It can move on people.

“The virus can pass on — on trucks, on equipment, on feed, on feet,” he said.

So, being aware of interactions with other farmers, birds and the outside environment is crucial. Turner said there’s been reported spikes of transmission events during annual bird migrations.

Chris Scheodel sprays her shoes with disinfectant after visiting a feed store in Conyers, Ga.

After the Elbert County cases, the Department of Agriculture issued a suspension on all poultry exhibitions, shows, swaps, meets, and on live bird sales such as at flea or auction markets to limit disease spread. That suspension was lifted Monday.

Although it’s very transmissible, H5N1 is easy to kill. Turner recommends using high temperatures to disinfect equipment, but disinfectant sprays work too.

Chris Schoedal uses Lysol to disinfect her shoes before any interaction with her chickens. With the exception of those who provide her chickens with veterinary care, Schoedal said she hasn’t let anyone near her 16 chickens for about three years.

“These are my leaving-the-house shoes,” Schoedal explains outside a feed store in Conyers. “I have slippers I wear in the house, and then boots I wear out to the coop.”

She also has dedicated coop clothes. Her coops back home are covered with metal roofs and the walls are made of a welded wire, with smaller holes that chicken wire, to protect from predators but also from contact with other species.

Scheodal lives just 40 miles from Clayton County, where a backyard flock of chickens and ducks were infected with avian influenza in early January.

Schoedel's birds get tested for avian influenza twice a year and for salmonella strains once a year. Scheodel said though it may seem extreme, measures like this have worked, and that she’ll probably maintain her biosecurity “forever.”

“The worst I've had in my flock lately has been just a little injury on a foot,” she said.

As a moderator of some backyard chicken Facebook groups where misinformation on bird flu can spread quickly, Schoedal said she’s been encouraging other chicken owners to implement their own safety measures if they haven't already. So far, her chickens and her neighbors’, have stayed healthy, and she’d like it to stay that way.

“The measures we take to protect against AI (avian influenza) also protect against a lot of other diseases, too,” Schoedal said. “If I somehow, by my own fault, get them sick, I would feel terrible. I don't want to make my pets sick.”

In Decatur, backyard flock owner Kyo Brown said she’s more than happy to follow guidance on biosecurity, but at this point, isn't too concerned about avian influenza.

Decatur resident Kyo Brown keeps her backyard flock of chickens in a coop to protect them from predators. Prohibiting free ranging is just one biosecurity measure that chicken owners and producers are encouraged to take as highly pathogenic avian influenza spreads across the U.S. and across species.

Her chickens live in an outdoor, covered coop and aren't allowed outside. After nine years, she says they've had no issues with disease even though she doesn't do annual testing.

"Our chickens in particular, there's no way for anything to access them," Brown said. "This setup feels pretty safe."

Samples from backyard chicken flocks like Schoedal’s get sent to the Athens Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory at the University of Georgia. This lab also gets samples of milk to test for H5N1.

Another lab in Gainesville tests samples from commercial chicken flocks in Georgia. Both labs work with the USDA under the National Animal Health Laboratory Network and receive federal funding.

“We are ready and prepared all the time to rapidly respond to any high consequence pathogens,” lab director Binu Velayudhan said.

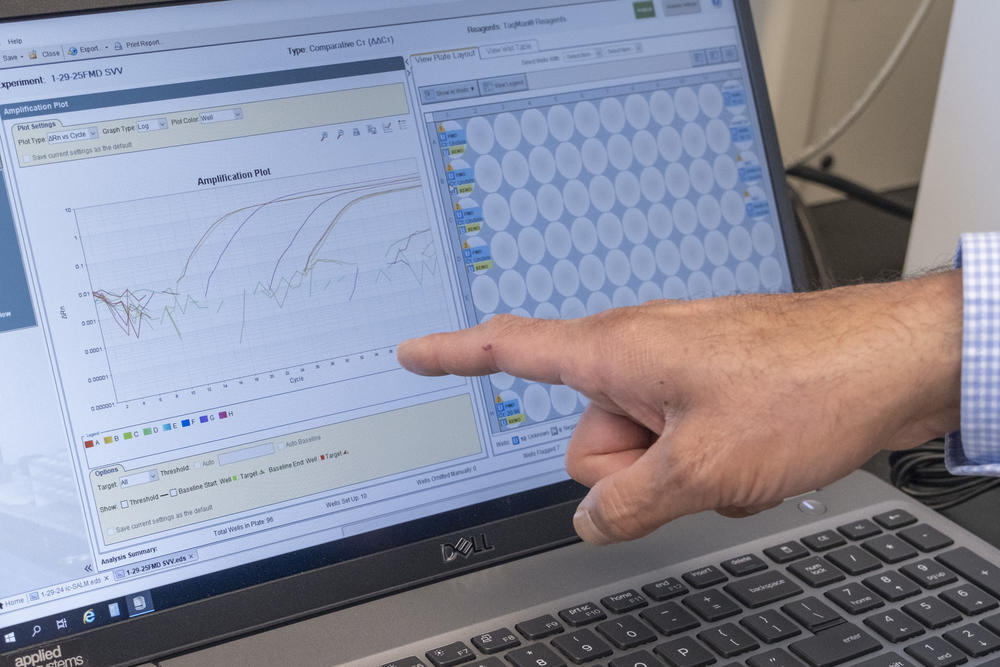

Binu Velayudhan, director of the Athens Veterinary Diagnostic Lab, says lab techs look for curves to indicate a non-negative sample. Pictured here is a sample for a foot and mouth disease common in pigs, but these same machines test samples for avian influenza.

Any “non-negative” results from a test for avian influenza gets sent to the National Veterinary Services laboratory in Ames, Iowa, where the sample is tested again. It’s not until they get a positive there that the public is notified, typically within a couple of days.

Velayudhan said they haven't received many samples for bird flu in Georgia over the course of the current outbreak. These days they test about one sample a week.

“The risk for the general public is still very low,” Velayudhan said.

But scientists warn that even though the spread from animals to humans has so far been pretty limited, H5N1 could pose a threat to human public health at a larger scale if it goes unchecked by state and federal agencies.

Avian influenza, like COVID-19, is a zoonotic disease, meaning it can be passed between animals and humans. Grazieli Maboni, a microbiologist at the UGA lab, said since the pandemic, scientists have learned how critical testing and surveillance are.

“We know that diagnostics is essential and we need, you know, to invest in that,” Maboni said. “If we can detect at an early stage … we can avoid that we spread to the human population as well as other animals.”

While that spread has already happened, there’s still a lot that’s unknown about how — and tracking the virus may be the best way to find out.