Caption

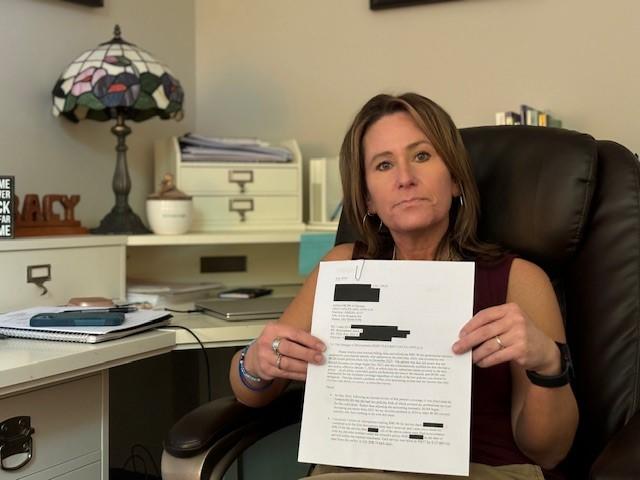

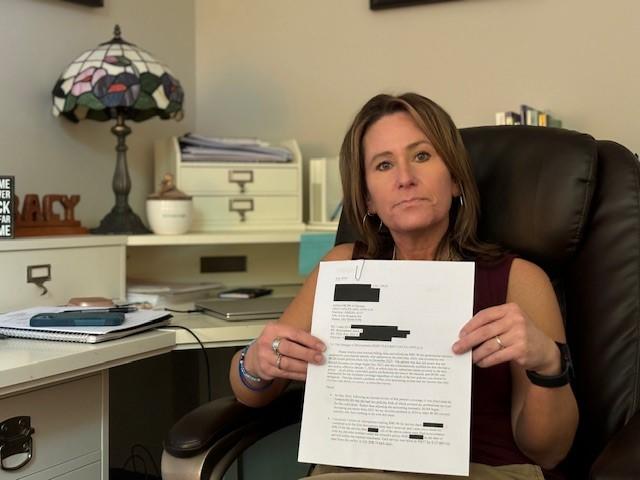

Tracy Hooper holds a redacted letter from her insurance company. Hooper said the company blindsided her by demanding reimbursement for what amounted to six months’ worth of sessions with a client.

Credit: Ellen Eldridge/GPB News

|Updated: April 2, 2025 7:55 PM

LISTEN: Many therapists want to be accessible to clients with insurance, but doing so is risky when billing errors and complex coding rules lead insurance companies to "claw back" previously paid reimbursements. GPB’s Ellen Eldridge reports.

Tracy Hooper holds a redacted letter from her insurance company. Hooper said the company blindsided her by demanding reimbursement for what amounted to six months’ worth of sessions with a client.

Many therapists want to be accessible to clients with insurance, but doing so is risky when billing errors and complex coding rules lead insurance companies to "claw back" previously paid reimbursements.

Tracy Hooper is one of a dwindling number of licensed professional counselors (LPCs) in Georgia who still takes insurance, even when it costs her business more to do so. Everyone else in her practice, located about 40 miles north of Atlanta in Holly Springs, has clients who pay out of pocket for mental health care services.

The insurance company Hooper has been working with for many years blindsided her by demanding reimbursement for what amounted to six months’ worth of sessions with a client — a year later — over a billing issue.

"They realized that they paid out of the wrong plan — which I have no way of knowing which one is primary," she said. "And then they came back for all of the money."

This clawing back of payment is devastating to business owners like Hooper.

Georgia has consistently ranked at or near the bottom of the nation when it comes to access to affordable mental health care.

While a workforce shortage is often blamed, insurance company practices are driving therapists into private practice.

Mental health care and substance use disorder treatment providers negotiate discounted rates with insurance panels so that clients have access to covered services. But more and more people are saying the business model is unreliable.

“Imagine it’s payday: You're expecting your paycheck to look a certain amount,” Hooper said. “And then your boss comes in and says, ‘You know what? I'm unhappy with the job you did two years ago, so, sorry, you're not getting paid this week.’”

When Hooper called the insurer about her contract, company representatives sent her in circles, forcing her to spend hours of unpaid time trying to recoup lost payment.

“The people making the decisions aren't the ones answering the phone,” she said.

Another problem is that reimbursement rates haven’t increased alongside inflation — if at all, said Tami Mark with RTI International, a nonprofit, nonpartisan research institute.

"What we're finding is that health plans will work really hard to get most specialists to participate in their network by paying them adequately," she said, "but they're not really doing that same work for psychiatrists and psychologists and other behavioral health specialists."

Some medical/surgical doctors are paid up to 70% more than psychiatrists, who diagnose and prescribe medication for behavioral health issues, she said.

"If the health plan is not going to reimburse them enough to participate, they're not going to participate," she said.

Amanda Marks, an LPC in Cobb County who specializes in treating substance misuse, complex trauma and eating disorders, has never accepted insurance — except for employer assistance programs.

Those programs matched her private pay rate, paid quickly and required minimal paperwork — at first.

“However, they've given me one pay raise and that was two years ago,” Marks said. “And then recently they started decreasing providers' rates, saying that they were too high, and they were going to stop showing the profiles of providers who they deemed had too high of a rate.”

But those providers' rates aren't arbitrary. Maintaining certifications and staying abreast of the latest advances in behavioral health care takes time and money.

“The insurance companies don't like to pay us what we're worth,” Marks said.

Also, the application process to get credentialed for insurance panels can be overwhelming.

“I attempted the process years ago and then just, in complete honesty and transparency, got overwhelmed and stopped because I felt like I would need a lawyer to help me understand the contracts,” she said.

Providers who are offered low reimbursement from insurers are less likely to participate in networks, resulting in smaller provider networks, more out-of-network use, and less access to necessary and appropriate treatment for Georgians, said Dr. Henry Harbin, a parity expert and advisor on RTI’s study.

"What this study showed is that the gastroenterologists and other specialists are paid 50% to 70% more than psychiatrists, psychologists," Harbin said. "So, they're willing to pay this additional funding in order to have an adequate network [of surgeons], but they're not willing to do that for mental health professionals — inpatient or outpatient."

That's because the big health insurance companies are publicly traded corporations that want to maximize profits for shareholders, said Matt Lavin, a health care and commercial litigation lawyer.

“They like to say that they're in the business of reducing health care costs,” Lavin said. “But what they're really in the business of is reducing access to health care for patients and putting health care providers out of business. You know, making things more expensive.”

Many providers and patients don’t have the knowledge or time to push back against these illegal disparities.

"It's clear that it's a parity violation," Mark said. "It's not something that is questionable."

In 2008, Congress passed the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, which requires commercial health plans to provide benefits covering behavioral health care treatment in a manner that is “no more restrictive” than that used for all other medical/surgical services.

That means a night in the hospital for a panic attack must be covered the same as a night in the hospital for a heart attack.

Georgia's 2022 Mental Health Parity Act is meant to better enforce the federal law from 2008, but, two years into it, detailed data to point to where these violations are is not available.

Enforcement is the trick, said state Rep. Mary Margaret Oliver, an Atlanta-area Democrat.

"We see the problems and can identify gaps," Oliver said, but the Office of the Commissioner of Insurance did not report data on insurance parity violations.

The combined annual data call for mental health, which includes autism spectrum disorder, ensuring compliance with mental health parity and autism spectrum disorder, was due to be sent to the governor, lieutenant governor, and speaker of the House of Representatives by June 15, 2024.

To address enforcement of parity compliance, legislators are asking for more oversight of mental health insurance coverage in Georgia, said Rome Republican state Rep. Katie Dempsey, who is sponsoring the bill and who chairs the House budget subcommittee for human services.

The bill would create a formal mechanism to review and address complaints through a proposed parity compliance review panel, and it would require health care providers to report suspected violations by health insurers.

“Our insurance industry has not recruited and paid mental health providers in a way that they are likely to join the panels of providers,” Oliver said. “That needs to be addressed.”

Back in Tracy Hooper’s office, she still has no clarity on her insurance contract, but they stopped taking money from her reimbursement checks.

She doesn’t know whether it will start up again.

Georgia Public Broadcasting is part of the Mental Health Parity Collaborative, a group of newsrooms that are covering stories on mental health care access and inequities in the U.S. The partners on this project include The Carter Center and newsrooms in select states across the country.