Caption

The Virginia corporate headquarters of Averhealth, which also does business as Avertest, LLC, is seen in this photo made available on their website.

Credit: averhealth.com

Kristen Clark-Hassell had already endured plenty of loss before she appeared in Camden County Juvenile Court in early 2021. Her first husband, a diver for the Navy, was killed in a motorcycle accident; her second died in a standoff with police.

But nothing prepared the 44-year-old St. Marys mother for the moment when the Camden judge, acting on the recommendation of Georgia’s child welfare agency, removed her newborn daughter from her care to a foster home.

“They literally took her off my breast in the hallway with her screaming after the court hearing,” she told The Current.

The judge’s decision came despite a string of conflicting tests for illegal drugs while she was pregnant: the state’s, some of which showed traces of methamphetamine; and her own, which showed she was clean.

Unknown to all the parties at the time was that Averhealth, the nationwide company Georgia paid to test her and thousands of others for drugs, was embroiled in allegations of widespread testing problems in its St. Louis laboratory, according to a whistleblower complaint filed in Michigan.

Averhealth’s lab director alleged in the complaint that up to 30% of the company’s tests were unreliable because of poor testing protocols, and the accusations were substantive enough to cause the U.S. Department of Justice to launch a 17-state investigation into false claims where the company did business. Georgia was one of the states.

Averhealth, which also did business as Avertest, LLC, settled the Michigan case in June 2024. It admitted no wrongdoing and paid $1.3 million to the U.S. government. The U.S. government did not pursue claims in any other states.

The lab director’s allegations covered the period in 2020 when Averhealth’s lab returned positive tests on Clark-Hassell’s first samples. At the time, Averhealth performed about 58% of the drug tests for Georgia’s child welfare agency, according to a company lobbyist.

The Virginia corporate headquarters of Averhealth, which also does business as Avertest, LLC, is seen in this photo made available on their website.

The Current investigated how that department of the Division of Family and Children Services (DFCS) handled the allegations against Averhealth and found that:

DFCS has a difficult job. It is charged with protecting Georgia’s children from neglect and abuse, while balancing the rights of parents and families. Its legion of county caseworkers investigate accusations of child maltreatment. After investigating, caseworkers support families with services, or seek temporary custody if children are at risk of harm, a process requiring a judge’s approval.

DFCS then finds alternate homes for those children: with foster parents, among relatives or in group homes. At that point, caseworkers and judges work together to reunify families, or, if all else fails, sever parental rights and adopt the children out to other families.

Drug testing is ubiquitous throughout the process.

According to DFCS’ policy manual, drug tests are used to evaluate parents, incentivize them to get treatment and support their recovery from a substance use disorder. Juvenile court judges often order drug testing and DFCS facilitates.

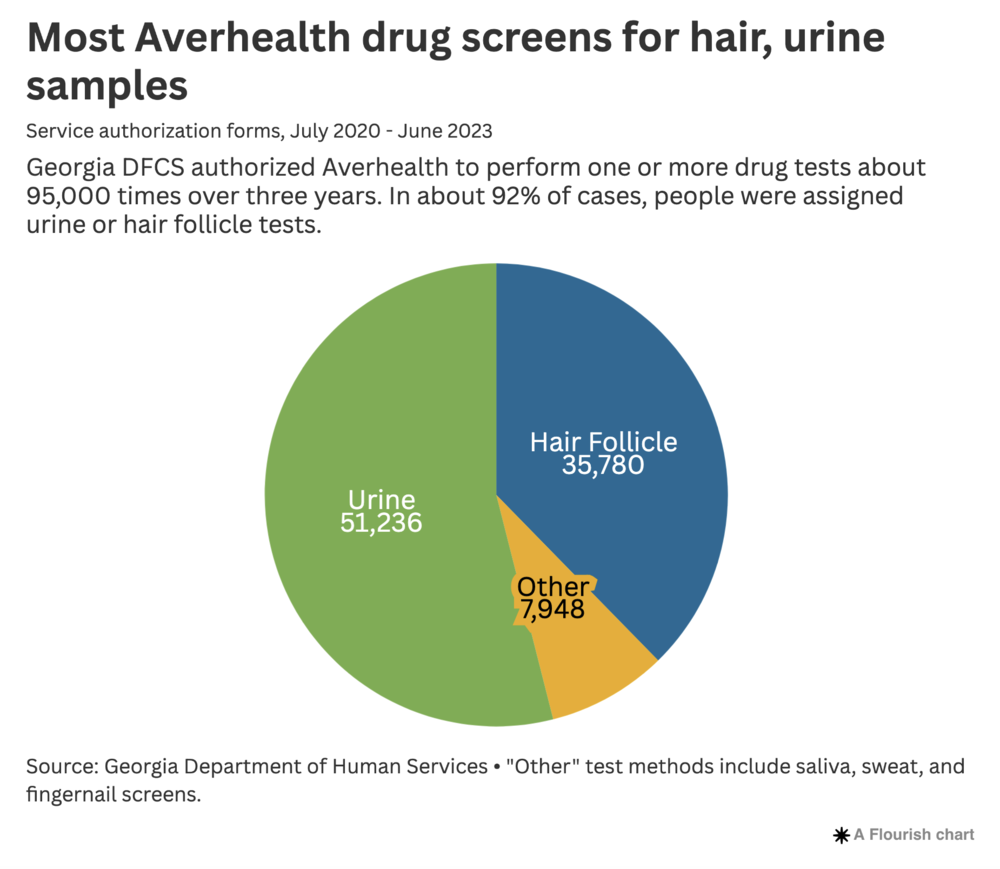

A majority of tests involve urine samples, according to The Current’s data analysis of testing referrals in Georgia since July 2019. But about one-third of all tests conducted for DFCS were an attempt to identify illegal drugs on hair samples, the data shows.

Courts and other governing bodies in other states have said that hair follicle testing is unreliable and biased against certain ethnic groups. Georgia’s Department of Community Supervision, which oversees one of the highest number of people on probation in the country, does not use hair follicle testing to ensure sobriety compliance.

Positive results have enormous consequences. About 41% of Georgia children removed to foster care were taken partly because of caretaker alcohol or drug abuse, according to the most recent year of federal statistics. For Georgia children under the age of one in foster care, 61% were removed for parental drug or alcohol abuse as a factor, higher than the national average.

Drug tests also affect parental visitation and whether a judge or caseworker determines a parent is ready to be reunited with their children.

“A parent can have all the rest together, but a dirty hair follicle and suddenly they’re thrown backwards in the case,” said Emilie Cook, attorney with the Barton Child Law & Policy Center at the Emory University School of Law. “It’s a huge setback.”

Averhealth CEO Dominique Delagnes declined to be interviewed about the company’s contract in Georgia. She said in an email that Averhealth settled the false claims case “to avoid the cost and distraction of litigation” and maintained that the company’s test results were accurate, then and now.

“Averhealth understands the scrutiny of its testing regimens and protocols given the level of trust our clients place in us. We welcome this scrutiny because we are confident in the work that we do,” Delagnes wrote.

DFCS Director Candice Broce declined to be interviewed, and instead responded to written questions about The Current’s findings.

“A drug test alone is not used to substantiate allegations of child abuse or neglect or for making decisions regarding child removal, family reunification, or termination of parental rights,” Broce wrote, noting that judges ultimately make such determinations based on many other factors.

Broce, when she learned that two other states had audited Averhealth test results, said her agency would be interested in learning more about that.

“We are open to conducting our own” audit, Broce wrote. “We will look into their methods and the final results.”

Michigan, which stopped working with Averhealth when the U.S. Justice Department probe started, declined to comment on what its audit revealed. Utah said its review, more limited in scope, resulted in zero findings of inaccurate tests. It no longer contracts with Averhealth.

Since fiscal year 2020, Georgia authorized nearly 95,000 referrals for testing through Averhealth.

If an audit ever happens, it would likely be too late for Clark-Hassell.

Clark-Hassell was 40 and pregnant with her ninth child when DFCS requested she take a drug test through Averhealth in August 2020.

The request confused her, she said.

Two years earlier, DFCS had taken custody of five of her children during a low moment of her turbulent life, citing poor supervision, an unclean house and an inability to reach her.

“There was no drug issue in the past, and no speculation of it, other than all of a sudden, now I’m pregnant,” Clark-Hassell said.

Life hadn’t always been this way for the native of upstate New York.

She’d wanted a large family, she said, and got a chance to start one when her father’s work as a Navy chaplain led her to her first husband, Kevin Clark, when she was 17.

They attended the Navy Birthday Ball together and were inseparable, she said.

Kristen Clark-Hassell sits next to the man who would become her first husband, Kevin Clark, at the Navy Birthday Ball. Clark-Hassell met her future husband when she was 17-years-old at a military base where her father was chaplain. He died in 2005.

By 2004, she was married to Kevin and raising their three children in Virginia Beach. Kevin had gone on to become a diver for the Navy and served overseas.

“I think having kids kind of made the time go by faster,” Clark-Hassell said. “I still had a piece of him left with me.”

But Kevin returned from Iraq with untreated trauma, she said, and, in the fall of 2005 he was killed in a motorcycle crash.

Her children, all under the age of 5, did not understand why their father hadn’t come home. She raised them while dealing with her own grief, she said.

Rebuilding her shattered life, Clark-Hassell moved to Georgia, where her father served as a chaplain at the naval base in Camden County.

She trained to become a police officer and served briefly on the St. Marys force.

She remarried in 2008 to Robbie Dane, a friend of her first husband. They lived in St. Marys together with five children. The stability Dane brought ended abruptly in 2009.

St. Marys Police shot Dane during a standoff while serving a bench warrant on an allegation that did not involve Clark-Hassell.

Clark-Hassell married for the third time in 2011 and had two children with Travis Hassell, a former Marine. They separated after she criminally accused Travis of abandonment, according to court documents.

Travis Hassell, reached for comment by The Current, said the couple separated because of what he described as an untreated mental health problem for Clark-Hassell, something she disputes.

“It became so toxic and so challenging that it was unsafe for me to even be in the house,” he said. Travis told The Currenthe was found not guilty of abandonment in Virginia.

Clark-Hassell said that was not true. She said she was not only in counseling at the time but also was left to fend for herself with multiple children after Travis left.

In 2016, Clark-Hassell became pregnant with her eighth child following what she described as a sexual assault by a man in Arkansas.

Travis filed for divorce in May 2017, and when it was finalized more than a year later, the Camden County judge had given primary custody to the father.

A St. Marys mental health counselor treating Clark-Hassell at the time wrote in a report that the mother made progress in therapy despite dealing with “high stress events” from her marriage and divorce.

“Ms. Clark-Hassell appears to be devoted to her children’s care and all interactions I have witnessed between her and her children has been healthy,” licensed counselor Carmen Calatayud wrote. “She has made good progress under extreme circumstances.”

Travis, however, said he and the court-appointed guardian in the divorce became concerned about the state of the home and care provided by Clark-Hassell. The guardian reported her to DFCS in late October 2018.

The guardian’s allegations included neglect, a dirty home and disregarding court orders in her divorce case, according to the order from Camden County Juvenile Court Judge O. Brent Green, who approved their removal to foster care.

Green presided over both Clark-Hassell’s divorce and her child custody case.

The divorce, loss of her children and eviction from her home following DFCS’ removal brought her self-esteem down to new depths, she said.

“I was living in my van with my two dogs because I felt like the biggest piece of shit and I wasn’t worthy to have a damn place to live, not even under my mother’s roof,” she said.

Clark-Hassell spent the next two years getting her life in order, focused on getting her children back. She was treated for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder, according to medical documents The Current reviewed.

She got a job working construction, bought a three-bedroom house in St. Marys in July 2020, and received counseling and medical care — all items that DFCS and judges look for when determining whether a parent is ready to reunite with their children.

Clark-Hassell also became pregnant with her ninth child, Jane, with the man she was dating. (The Current has changed the child’s name to protect her privacy.)

Her daughter’s impending arrival brought back hope and excitement to her scattered family, she said. Two of her children had returned from foster care, and Clark-Hassell hoped for the others to come back, too.

Then came the drug tests.

At the time Averhealth contractors came to her house and collected samples of her hair and urine, the company was facing business challenges in both Georgia and at its central testing lab in St. Louis.

Averhealth was the primary drug testing provider for DFCS in Georgia, but its centralized process of collecting and testing samples for so many DFCS clients was proving unwieldy, according to Tom Rawlings, the agency’s former director.

The day the company was collecting Clark-Hassell’s samples, DFCS released a solicitation seeking new testing providers localized across the state. The solicitation excluded Averhealth from a list of four laboratories that providers could work with.

Kristen Clark-Hassell, of St. Marys, shows her voluminous files resulting from years of DFCS involvement in her children’s lives.

Two weeks later, Averhealth wrote a letter through its Georgia lobbyist, Stanley S. Jones, Jr., pleading for the state to reconsider.

The 65 counties that used Averhealth for a majority of testing should be allowed to stay with the company, Jones wrote.

The lobbyist pledged that keeping Averhealth would save Georgia $1 million annually. He also threatened that Averhealth would file an official protest if the solicitation was not changed.

“Averhealth hereby requests that the Division amend and re-release the Solicitation to include Averhealth on the list of designated labs,” Jones wrote.

About two months later, DFCS released a new solicitation that allowed providers to work with any laboratory they wished. It only required providers to use a certified laboratory that followed the national guidelines for testing standards.

Rawlings told The Current that he did not remember the lobbyist’s letter, or know why the solicitation was changed in such a way that Averhealth could remain a drug testing provider.

“My understanding was that we were going a different route,” from Averhealth, he said. “I still don’t quite understand how that didn’t happen because I thought that was what we all had agreed to do.”

Broce said she could not comment on Averhealth’s letter because it occurred before she started as director.

Meanwhile, the company faced a more serious crisis at its testing lab in St. Louis. During the fall of 2020, Dr. Sarah Riley, a forensic toxicologist who was hired to head Averhealth’s lab, observed troubling lapses in testing protocols, according to the whistleblower complaint.

Riley brought her concerns to management. She said those concerns were ignored, and she subsequently resigned. She submitted them to a national accreditation agency, the College of American Pathologists (CAP). In early 2021, CAP put Averhealth’s accreditation on probation for six months, according to a letter from the organization.

By March 2021, Riley’s allegations had formed the backbone of the justice department’s false claims suit against Averhealth.

Averhealth’s lab repeatedly “manipulated data” to meet contractual deadlines, according to the whistleblower suit.

“To an untrained eye, Avertest ‘results’ would not raise a red flag,” the suit said. “However, the results were not accurate and had no scientific basis because they were not backed by internal standards, calibration curves or quality controls.”

The suit continued: “Dr. Riley discovered that the issues with the screening and confirmatory testing were widespread throughout the lab and were long standing issues that had been occurring at Avertest for months, if not years.”

The company’s “actions have resulted in significant negative impacts on families and children across the country,” the suit concluded.

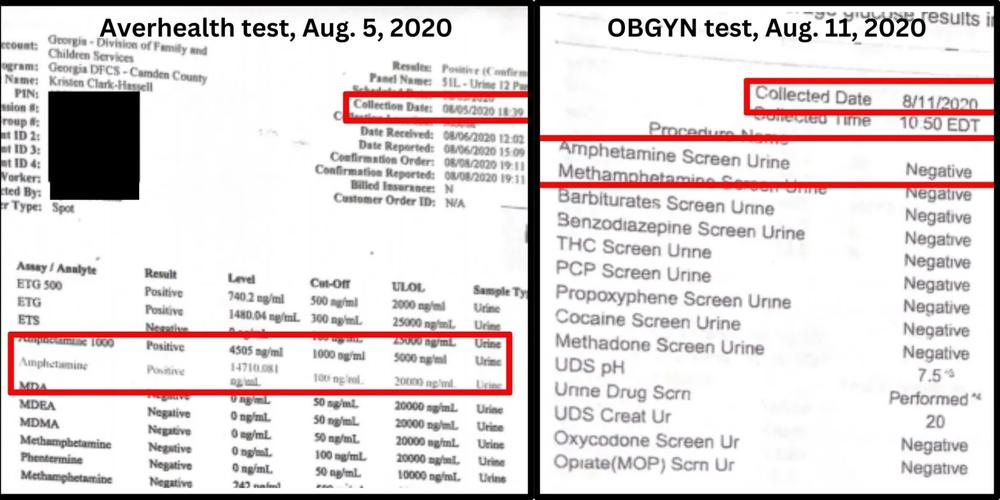

The samples Averhealth took from Clark-Hassell in August 2020 tested positive for amphetamine and methamphetamine, both illegal stimulants.

Clark-Hassell was stunned.

Six days after the first collection from Averhealth, Clark-Hassell received a urine screen during a visit to her OBGYN, and the test showed as negative for these illegal substances, according to documents reviewed by The Current.

The Current interviewed two drug testing experts about Clark-Hassell’s tests. One expert said that potential methamphetamine could have been out of her system in a urine test six days later. The second expert, however, stated that a positive test could also have resulted from Clark-Hassell’s prescribed medication for AD/HD.

Six days after testing positive for illegal drugs, Kristen Clark-Hassell tested negative for the same substances.

In September 2020, she took a urine test, this time through Camden County Drug Court. The result was negative, according to the testing record. She thought the OBGYN result, part of standard medical care, and the drug court result, which she sought out, would prove to DFCS she did not use drugs.

“If I was hiding something, then I sure as hell wouldn’t have all of this proof,” she told The Current. “You know what I mean? The drugs would be the priority in my life. … but that’s not. It’s my kids.”

DFCS authorized another random drug screen through Averhealth in October. Clark-Hassell’s urine screen was negative, according to the testing record. But her hair tested positive for methamphetamine, at levels higher than before.

The conflicting results did not seem to matter to DFCS, she said.

In November, Dr. Riley resigned from Averhealth because of her concerns about the accuracy of its tests, according to the whistleblower suit.

Kristen Clark-Hassell visits with her daughter Jane, who was born in early 2021 and taken into custody by Georgia’s child welfare agency, following positive drug tests by her mother conducted by Averhealth. Clark-Hassell said she never missed a visit with her daughter while she was in foster care.

Two months later, Clark-Hassell gave birth to Jane. Clark-Hassell’s OBGYN reported no health issues when she discharged the mother and child from the hospital three days later, according to hospital discharge documents.

Six weeks later, DFCS took custody of Jane and placed her in foster care, citing Clark-Hassell’s positive drug tests from the previous year.

Clark-Hassell’s large family was reduced to two sons, whom she said had been looking forward to having a sister.

“Everybody was so happy to have her,” Clark-Hassell said. “And then for her to just be ripped like that just cut a hole in our hearts.”

Jane’s foster parent lived a 25-minute drive away from Clark-Hassell’s home in St. Marys. Throughout 2021 and 2022, Clark-Hassell was allowed to visit her daughter twice a week. She brought her other children with her on the visits.

She was constantly worried about her newborn’s treatment in foster care, she said. In two years, Clark-Hassell said she never missed a visit.

In its case plan for Jane, a DFCS caseworker wrote that Jane needed to be “in an environment free from methamphetamines’ use.” The plan required Clark-Hassell to undergo random drug screening, take parenting classes and be assessed for substance abuse, in order to be reunited with Jane.

In September 2021, a court-appointed special advocate, or CASA, which is a trained citizen assigned to advocate for the child in court, wrote in a report that Clark-Hassell had steady income from a construction job and her military benefits, and maintained a clean home. Most importantly, she wrote, drugs did not appear to be an issue, according to the CASA’s notes.

“She does not abuse drugs,” Sherry Walker, the CASA, wrote. “She doesn’t even use them.”

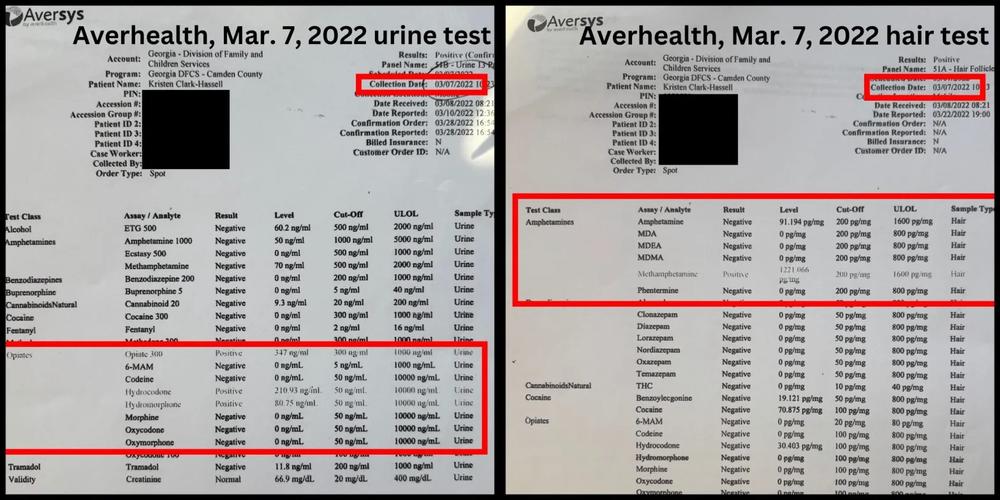

On March 7, 2022, Clark-Hassell’s urine tested positive for opiates and her hair tested positive for methamphetamine through Averhealth, according to test records.

Drug tests by Averhealth on March 7, 2022, which found Clark-Hassell positive for opiates and methamphetamine.

“I started getting like, ‘What the heck’s going on here?’” she said. She began getting her own drug tests routinely, she said.

“So if they did a (test), I went to Camden County Drug Court and did one the same day or went down to Jacksonville, Florida, and did one the day after. Right as soon as I could or (had) the money to do it.” She paid out of pocket for the tests, she said.

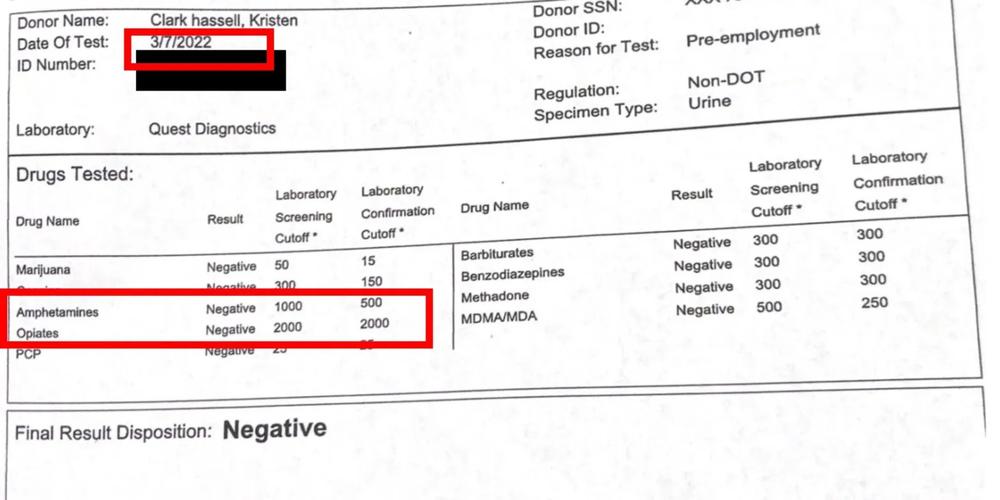

On the same day as the positive test in March, she tested independently at a Jacksonville urgent care that did workplace drug testing. The urine results were negative for opiates and amphetamines, which is the class of drugs encompassing methamphetamine, according to test records.

Independent drug test in Jacksonville which reported Clark-Hassell as negative on Mar. 7, 2022, which was the same day as her Averhealth positive tests.

In April 2022, she went to the local addiction treatment provider, Gateway Community Service Board. DFCS required that she undergo a “substance abuse assessment” as a condition to regain custody of Jane, according to her case plan.

The center’s staff assessed her for mental health and substance abuse. The facility administered two drug tests without notice, and she tested negative. Gateway did not recommend any additional services and gave her a “notice of completion” to submit to the court, according to a letter from the provider.

That same month her hair tested positive for methamphetamine in a hair follicle test performed by Averhealth for DFCS, according to test records.

An expert consulted by The Current questioned how DFCS used drug testing in Clark-Hassell’s case and said the evidence of illegal drug use was inconsistent at best.

“We don’t just isolate one thing and give all of the meaning to that one fact,” said Dr. Mishka Terplan, board certified in obstetrics, gynecology and addiction medicine. “We look at all of it in context.”

“I cried uncontrollably when it was the last time I was allowed to see her,” said Kristen Clark-Hassell after losing the parental rights of her daughter. “I could not physically move.” She is seen here at a playground in Camden County, Ga., in 2024.

Drug tests are also not an appropriate tool to identify whether a person has a substance use disorder, according to Terplan. He said addiction is behavioral and drug tests can’t tell you about behavior. Drug tests are best used for patient monitoring while somebody is in active drug treatment, he said.

By mid-June 2022, DFCS had filed a petition to terminate Clark-Hassell’s parental rights of Jane, the most extreme outcome in a custody case. The motion cited Clark-Hassell’s “history of chronic unrehabilitated substance abuse,” as well as insufficient housing and employment.

The department also filed a motion to terminate parental rights for her two other sons for lack of supervision. DFCS litigated both cases over four days in August 2022. Clark-Hassell put up a vigorous defense with a private attorney. But it wasn’t enough.

Judge Green approved permanent termination of Clark-Hassell’s rights to Jane and her two sons.

Losing her newborn cut deep.

“I cried uncontrollably when it was the last time I was allowed to see her,” she said. “I could not physically move.”

Jane was adopted by another family, and Clark-Hassell hasn’t seen her daughter since. She said her two boys are living with a relation of her deceased, first husband.

The Current sent a list of questions to Camden County DFCS Director Laurie Kaler about the case. She declined to comment.A spokesperson for statewide DFCS did not respond to questions about Clark-Hassell’s case.

Around the same time as Clark-Hassell’s parental rights were terminated, DFCS renewed its contract with Averhealth.

Months earlier, DFCS head Broce, her staff and the Georgia attorney general’s office, were made aware of the federal government’s false claims investigation into Averhealth. DFCS also knew that the College of American Pathologists (CAP), the national accrediting body for laboratories, had placed the company on a six-month probation in 2021.

An attorney with the AG’s office, told Chris Hempfling, a top deputy and lawyer under Broce, that the justice department wanted to speak to someone about Averhealth’s contract with Georgia, according to emails reviewed by The Current. Hempfling passed that information onto his boss, according to those emails.

“Since DOJ is getting involved, I can provide you with a background of this during our 4 oclock today,” Hempfling emailed Broce on Nov. 2, 2021. “I don’t know much right now, but definitely sounds like something is brewing.”

A DFCS spokesperson told The Current that Broce was never briefed by Hempfling about Averhealth. Hempfling, who no longer works for the agency, did not respond to a request for comment.

In January 2023, Vice News revealed that the Michigan child welfare agency was cooperating with the justice department in an investigation into Averhealth. A Vice reporter emailed Georgia DFCS about its own contract with the company.

The inquiry set off alarm bells at DFCS.

“Do we still consistently use them? Those news reports are startling.” Broce wrote to her senior staff on Feb. 10, 2023, according to emails.

In a later email, Broce wanted to understand the drug testing landscape at her agency.

“Can you find out from (staff) how many other drug testing vendors we’ve got contracts with, and also get a sense of how often people use AverHealth? It sounds like we need to immediately suspend utilization,” she wrote.

DFCS staff told Broce that the agency had received complaints about the accuracy of Averhealth’s tests.

A week after Broce was contacted by Vice, DFCS conducted an annual assessment of Averhealth’s contract. It concluded Averhealth posed too great a risk to renew.

While the department’s own policy required a risk assessment every year before renewing, DFCS was only able to produce a single assessment, the one from 2023, when The Current filed a public records request. DFCS renewed its contract with Averhealth five times since 2018.

Following the 2023 assessment, the agency allowed the contract to expire without renewal that June. Invoices through the Georgia state auditor show that Averhealth was paid $13.2 million during the five years of the contract.

Broce told The Current it was not possible to end the contract earlier than DFCS did. She said the agency has drastically changed how it oversees contractors since she took over in 2021, hiring more contracting lawyers to help staff evaluate performance.

“We’ve completely overhauled the agency’s contracting and procurement processes, which were dysfunctional and lacked sufficient accountability for contractors’ performance,” Broce wrote in an email to The Current. “Now, we have better people, processes, and technology in place.”

The AG declined Open Records Act requests sent by The Current related to Averhealth, citing attorney-client privilege and confidentiality of evidence.

The AG’s office declined to make the staff involved available for an interview with The Current and said it was uninvolved in the justice department investigation into Averhealth.

“We were not involved in the filing of the case, but it was necessary for our office to consent to the dismissal to comply with Georgia law,” the AG’s spokesperson said.

Kristen Clark-Hassell, of St. Marys, Ga., graduated with honors from an online master’s program from Adler University in Chicago in October 2024. She is seen here with her parents.

Clark-Hassell is scarred by her experiences with DFCS.

“It’s hard to keep going every day,” she told The Current.

She worries about the mental health of her oldest son who is now 24. He took Jane’s removal especially hard, she said.

Clark-Hassell has stopped law enforcement work and instead is employed at a home-repair shop in Camden County.

In October she graduated with honors from an online master’s program from Adler University in Chicago. She intends to combine her psychology degree with her still-active Georgia police certification to become a military/first responder and mental health counselor in Camden County.

She hopes to leverage her military knowledge, law enforcement training and psychology education to treat people who struggle with their mental health.

Clark-Hassell said she is not done fighting to get her children back and has achieved some victories.

Last month, a Superior Court judge granted Clark-Hassell a new trial in a custody case involving one of her children. The judge’s order found that the earlier decision to terminate her parental rights ran “contrary to the evidence and principles of justice and equity,” according to an order viewed by The Current.

She also hopes that telling her story about drug testing and DFCS spreads awareness to others across the state.

“I just want my kids,” Clark-Hassell said.

“If, God, for some unknown reason, I don’t get them,” she continued, “then maybe it can change something to where other people don’t have to go through this.”

Additional reporting and data analysis by Maggie Lee. This project also received editorial support from the Investigative Editing Corps and financial support from Report for America and the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current.