Section Branding

Header Content

Blue Ray by Tony Whedon

Primary Content

Inspired by painting, poetry, and jazz, poet Tony Whedon says he "can't wait to get to that computer every morning to see what's going to happen." Join Peter and Orlando as they explore Blue Ray, a collection of poems by Tony Whedon of Darien, Ga.

Peter Biello: Coming up in this episode.

Orlando Montoya: It sounds like that — that he's really dealing with some — some very, very strong loss there.

Tony Whedon: I found something new, not — I wasn't just discovering a new self. I was discovering something new about myself.

Peter Biello: And in this book, he dives into colors. He explores the art of painting, writes about Le Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, paying homage to the 15th-century illuminated manuscript —

Orlando Montoya: Glad you said that.

Peter Biello: This podcast from Georgia Public Broadcasting highlights books with Georgia connections, hosted by two of your favorite public radio book nerds, who also happen to be your hosts of All Things Considered on GPB radio. I'm Peter Biello.

Orlando Montoya: And I'm Orlando Montoya. Thanks for joining us as we introduce you to authors, their writings, and the insights behind their stories, mixed with our own thoughts and ideas on just what gives these works the Narrative Edge.

Peter Biello: This is going to be a special episode for me today.

Orlando Montoya: Why is that?

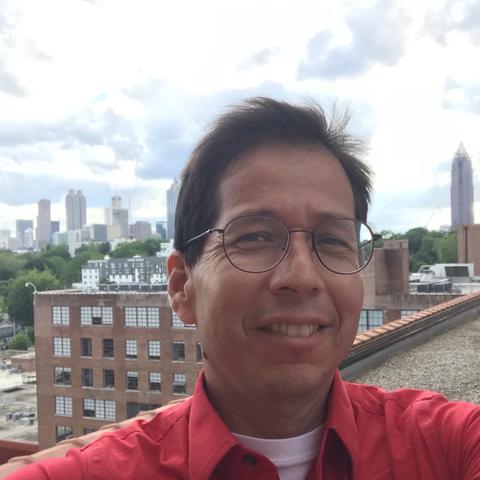

Peter Biello: Because we're featuring someone I've known for more than a decade. One of the most intelligent and creative people I have ever met. Poet, painter and jazz trombone player Tony Whedon.

Orlando Montoya: Is he a friend of yours?

Peter Biello: He — he's a friend. Tony lives in Darien, Ga., now. We first met in Vermont. It started off as just, you know, the kind of interview that I do here. I was doing them there in Vermont Public. It was known as Vermont Public Radio at the time. This was around 2011. He — Tony published a collection of poetry called Things to Pray To in Vermont. And I was introduced to—

Orlando Montoya: Things to pray to or things to pray for?

Peter Biello: Things to Pray To, Things To Pray To. And I was interviewing poets and writers back then, and somehow I got a copy of the book. I don't know how, probably a publisher just sent them to the office. And I read it and really liked it. And so I invited him for a studio interview and we kept talking. Once the mics were off, talking about writing. And this was a period in my life when I was running a writing workshop nonprofit, and I invited him to stop by. And he did. Anyway, Tony and I saw each other from time to time, sometimes when he was performing for his band, Po-Jazz.

Orlando Montoya: Po-Jazz.

Peter Biello: Yeah, poetry jazz, man. It's, it's emblematic of what he does to emerging art forms. I mean, Tony plays the trombone, as I mentioned, and during these performances, he'll — he'll read poems. Other — other poets will stop by and read their poems to, to a beat or some kind of tune. I don't have a recording of Tony right now, but I did want to play a little bit of Po-Jazz for you.

MUSIC

Orlando Montoya: That's too cool for me. I'm not allowed to experience that.

Peter Biello: That's Chloe Viner reading one of her poems. Not a lot is available out there on the internet about Po-Jazz, but they do have a double album that came out almost a decade ago. Anyway, you can't hear Tony in that one, but that'll give you a sense of what Po-Jazz is and the kind of art project that Tony is interested in.

Orlando Montoya: So today, are we talking about a book or jazz?

Peter Biello: We're talking about a book, but merging of art forms, that's kind of a theme. Tony's newest book is called Blue Ray, and it merges poetry and painting. I mentioned Tony was a painter. He's very interested in the art form, and in this book he dives into colors. He explores the art of painting, writes about Le Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry paying homage to the 15th-century illuminated manuscript.

Orlando Montoya: Glad you said that.

Peter Biello: I lived in France for a time. So I went to Darien recently and we met in his backyard for a conversation, and I asked him about the intersection of poetry and painting, and the answer went somewhere else pretty quickly.

Tony Whedon: These poems were written in Blue Ray over a period of about 15 years, and a lot of them are very recent. The most recent ones are about losing my wife to Parkinson's a few years ago, so there's a tinge of grief through everything. Even the joyful moments have that. But in some ways, I feel the book is unified and that it's, you know, it's got color and it's got "Blue" in it, but it's also unified by grief. But I don't seem — it's — I'm not celebrating grief because there's a lot, of lot to be happy about.

Orlando Montoya: And I'm sorry to hear his wife passed away.

Peter Biello: I was, too. Knowing Tony meant knowing Suzanne, his wife, and we'd met on several occasions. And, you know, they were a wonderful couple. They had a level of friendship that I think all married people aspire to. They lived in a house in Montgomery Center, Vt, way up near the Canadian border. And Suzanne was just really kind. I didn't know her as well as I knew Tony, but I did see how happy they were together. So I asked Tony what it was like to explore that loss in his poems.

Tony Whedon: Why don't I read a poem? Because that's the only way I can really handle that.

Peter Biello: What poem?

Tony Whedon: Okay, this is "Tachycardia":

The storm came fast and was nearly gone

before I went out to check the damage –

a patio table tossed over, our sweet

princess of a garden statue ensnared

in vines. A wild down-home rocker

of Low Country storm, & I felt your heart,

your poor heart, beating next me,

your breath coming way too fast.

A slash of lightning, preceded by

throat-clearing rumbles somewhere west

of the marsh, then you were awake,

your voice soft as a prayer. Nothing’s

to be done about it, you said,

and promptly fell back to sleep,

and I lay there awake till dawn.

Orlando Montoya: Wow.

Peter Biello: Yeah. What do you think of "Tachycardia"?

Orlando Montoya: Well, I like it that I like the storm and the lightning. It really brings me back there. But it also, you know, "tachycardia." Doesn't that mean heart attack?

Peter Biello: Yeah. Something like that.

Orlando Montoya: So it sounds like that — that he's really dealing with some — some very, very strong loss there.

Peter Biello: It's always difficult to talk about poetry collections as a whole, right? Especially if the themes are just there for the reader to experience. So to go back to jazz for a moment, I mean, trying to describe a collection of poetry is kind of like trying to describe jazz. Like, you can describe the instruments used or the meter, but the feeling is just something you got to experience. And I think that delivers a feeling like all these poems do well.

Orlando Montoya: It delivers a feeling of — of cold. I can feel the wind when I hear that.

Peter Biello: Yeah, the low country storm, the storm outside. Scary. And the idea of him sort of lying awake at night while, you know, his beloved is sick. But there's nothing to be done about it. Um — that just knocked me off my feet. I really enjoyed that.

Orlando Montoya: Well, you talk about, you know, you just have to feel the poems and you can't really talk about sort of what the poems are. You got to talk about the poet, what the poems are.

Peter Biello: I know—

Orlando Montoya: There's got to be a theme here.

Peter Biello: Well, I will say one experience of reading this book for me. You know, knowing that Tony has traveled widely. I mean, even if he didn't know that about him, you could glean that from the poems. He has traveled widely. He's — he's taught in China, visited Cuba, lived in France and in Greece. And seeing different countries named here in the poems, different personae in the poems, I had the impression that maybe Tony was trying on different identities in these poems, getting close to the figures inside paintings and some poems, sometimes identifying with a particular painter trying to create something, or literally trying to chase down an elusive figure in the painting. So I asked him about that. I asked him about the question of identity in these poems.

Tony Whedon: Visiting, you know, scores of countries. And each time I found something new and not — I wasn't just discovering a new self. I was discovering something new about myself — and something that touched a different sensibility. Now, you could say that we have different sensibilities and that they're all just separate glimmers of the self. I lived in northern Vermont in a cabin, and I wrote a book about it called Drunk in the Woods, and I was recovering from alcoholism. And during that particular time, I went through all kinds of transformations because of huge cold winters with 30 below and the struggle of surviving being poor. That was another self, but it was really just an — not an embellishment, but an enlargement of myself.

Peter Biello: An enlargement of the self.

Orlando Montoya: Are we talking about all the poems dealing with loss?

Peter Biello: No. They, they — That's the tricky part about this is that there are — there are some themes that you might just hang on with one word. Like the word "Blue," of course, coming through first in the — in the title and then in the first poem. And then if you spot it throughout as part of a collection, it has a different resonance. That's how I think these things tend to tie together. But as you mentioned also, some of the more recent poems were about losing his wife, which are very loosely tied, if tied at all, to the ones about painting. I mean, you can look for it if you'd like, or you can enjoy those poems as they exist on their own.

Orlando Montoya: You mentioned travel as well. Did other places come up in the poems?

Peter Biello: Yeah. I mean, there's one poem where — I believe it was Italy — there's a painter painting a figure of a woman, and and the woman kind of gets up and runs off and the painter ends up chasing. I loved this poem. And, you know, if it were — it's like three or four pages long, so I wouldn't be able to — to adequately read it on the air or in this podcast. But it's — it's a fascinating look, and that one had a trippy quality to it. I would say "trippy" is the only way I could describe it: chasing this woman down — down paths and that seem to change as you traverse them. It was it was cool. It was cool to see.

Orlando Montoya: What about a beat? Jazz has a beat. Did these poems have a beat?

Peter Biello: Well, let me ask you. Did you pick up a rhythm in "Tachycardia?"

Orlando Montoya: Sort of.

Peter Biello: Yeah. I mean, it's, it's — I would say that the the music is in there and it's, it's you have to have the ear for it to read it. We did talk quite a bit about identity, who you are in a poem and what it means when you're discovering yourself inside a poem. as the composer of that poem. I mean, he told me a story of his time in Paris in the 1960s. This is not — this is apart from what's in the book, but kind of informs how you understand his work, which is, you know, he was a big fan of jazz even back then in the '60s. And he walks into a club and there's the pianist Bud Powell — a legendary jazz player. And Tony described for me the image that stuck in his mind that compelled him to write recently.

Tony Whedon: And I started thinking about that today, and I wrote, what's this poem going to be about? It's going to be about Bud Powell in Paris. Now, what's happening is, of course, it's not Bud Powell in Paris. It's me remembering about Bud Powell in Paris, me trying to enhance what I saw before through all the years. So in a way, writing about the past is inaccurate. It's not the past. It's your take on it. But it's really a developing development of your impression of that time.

Peter Biello: So you can kind of tell Tony was a professor for a long time. He taught creative writing at Johnson State in Vermont.

Orlando Montoya: And so where— So you said — OK, so you guys met at the jazz club?

Peter Biello: No. We met — we met when I invited him to the studio at Vermont Public to talk about his — what was then his latest collection of poetry, Things to Pray To in Vermont. So it was really just — Imagine a source coming into the studio, and then you turn the mic off and you just really like — you're vibing with the person.

Orlando Montoya: Well, that happens. That's happened to me. I've made friends of people that I've interviewed.

Peter Biello: Not politicians. You can't do that with politicians—

Orlando Montoya: No.

Peter Biello: but with artists, sometimes it fits.

Orlando Montoya: And have you gotten his poetry over the years?

Peter Biello: Oh, yeah. I mean, he — you know, you meet a poet, you get on their mailing list, whether you're personal friends with them or not. And so I always know when a new book comes out, and this book came out last year, and I was looking for an occasion to talk to Tony about it. And it just so happens that.

Orlando Montoya: He lives in Darien.

Peter Biello: He lives in Darien. And as as listeners of this podcast will know, we were recently in Coastal Georgia, in Savannah for the Savannah Book Festival. And I thought, "Well, since I'm in the area, let me go down and talk to him," which is why we also had a conversation in his backyard. You know, he's — he's getting up there in years. So traveling is not a thing he likes to do as much. So it was — it was good for me to actually go to him, which is why we have a nice soundtrack of birds to our conversation when we were in the backyard. I will say this too, you know, I've gotten a lot of writing advice over the years tips on technique, you know, habits, whatever. Something Tony said to me once really stuck with me. I remember we were having lunch on Burlington's Church Street — which some listeners might know of Burlington's Church Street. We're talking about writing. And he said "The work is its own reward," meaning writing is its own reward. And that always stuck with me because, you know, writers can worry. We can worry about quality. We worry about potential audience for anything we're working on, about wasting time on an idea so bad that it can't be salvaged. But that advice meant a lot to me because he was essentially giving me permission to say, you know, "So what if the writing sucks? So what if nobody ever reads this?" I mean, this is for me. This is fun. This is satisfying. If I go into a project expecting fame and fortune, like, "Good luck, buddy, just just enjoy the ride," you know?

Orlando Montoya: Well, maybe you shouldn't say that in in terms of this, because the writing doesn't suck.

Peter Biello: The writing doesn't suck. Like, he — he was enjoying himself. And it turns out there's something here for for readers to enjoy as well. So he hit the jackpot there. Good use of his time.

Orlando Montoya: And how long is the collection?

Peter Biello: The collection is just, you know, 50 pages or so. It's pretty short. Yeah. And so anyway, when I had the chance to talk to Tony recently, I asked him if he remembered giving me that advice.

Tony Whedon: All the things we've talked about this interview, about finding out about yourself, about finding a different level ... layers of yourself, of different incarnations, as it were, are part of the process, and it's its own reward. That's the reward you get. It's a complex one, but each one of us, and each day we do it, it may be a different reward, but I can't wait to get to that computer every morning to see what's going to happen and see who I'm going to be today.

Orlando Montoya: I think I know why you like this guy.

Peter Biello: He's got a charm, right? He's rubbing off on you a little bit?

Orlando Montoya: I like the way he speaks and he gives advice. He's like a sage.

Peter Biello: That's — Yeah. I mean, he's my mentor, essentially. Like, I, I sent him — I haven't sent him any of my work in years. But when I did, the advice I got back was always very, very insightful. And I, I took it to heart. So I always appreciated what — what Tony has — has said about my own work.

Orlando Montoya: So — and so for people who aren't friends of the author, what gives this book the narrative edge?

Peter Biello: I think this is the work of a brilliant mind. I mean, we heard "Tachycardia" on this podcast and I hope people noticed the music in his lines. I mean, like jazz, I can tell you about it. And I have, but experiencing it is a totally different thing and I hope people do. I will say I don't love how writer friends scratch each other's backs in public forums. But that said, because I met Tony first as a professional source, I feel like I can be forgiven here. Like, I didn't find him, we didn't become friends and then I decided to put him on the air. It was sort of the reverse. I put him on the air and then we became friends. So that's — that's my plug for Tony. And by the way, if you're in Darien, be on the lookout for Tony as part of the Darien Jazz Quartet, which plays from time to time at the studio right in the center of town in Darien.

Orlando Montoya: I got another question.

Peter Biello: Sure.

Orlando Montoya: So what do these poems make you feel?

Peter Biello: It depends on the poem. It depends on the poem, for sure. Like, I — sometimes with poems you go line by line being struck with images, and each of those images gives you, I guess, the equivalent of an electric — like a tiny electric shock. And the accumulation of those shocks will leave me feeling either spent or energized or just stuck with awe. And. I'm sure there are more variations on the degree to which I can be struck by a poem, but more often than not, I'm — I'm left feeling this kind of, like I'm feeling something and I don't know what it is exactly. So then I have to sit back and and figure out, like, what does this — what does this make me feel? And I'll, I'll stick with "Tachycardia" just because we're all experiencing that together in this part podcast. Like, I literally felt like I was on my back at the end along with the, the, the voice at the center of that poem and also struck with like a feeling of helplessness, which I imagine is what the narrator also felt. Again, the line "Nothing can be done about it." There's — there's something terribly wrong going on there, and. Oh, my God, what do we do about it? Nothing. We just have to sit there and absorb it. And that for me was the, the, the biggest of the electric shocks that each line gives me. Does that make sense?

Orlando Montoya: Yeah it does. And another reason to like a poetry collection is that if you don't like it, you haven't spent hours and hours and days with it, as you might have with a larger book.

Peter Biello: Yeah. Some people need time to get acquainted with a text of any kind. I mean, if you know what you like about poetry, like, for example, if you're Billy Billy Collins-type reader — no slight to Billy Collins; he's a talented guy — his are a lot more straightforward, and I feel like Tony Whedon would not be a huge overlap with the Billy Collins crowd. That said, he's also not an e.e. cummings guy either. There is a story there. It can just get a little more abstract. It can hit you in a way that is a little slant, tells it slant, I should say.

Orlando Montoya: All right. The book is Blue Ray by Tony Whedon. W-h-e-d-o-n. Thanks for telling me about it.

Peter Biello: Happy to.

Orlando Montoya: Thanks for listening to the Narrative Edge. We'll be back in two weeks with a brand new episode. This podcast is a production of Georgia Public Broadcasting. Find us online at gppb.org/narrative edge.

Peter Biello: You can also catch us on the daily GPB news podcast Georgia Today for a concise update on the latest news in Georgia. For more on that and all of our podcasts, go to GPB.org/Podcasts

Inspired by painting, poetry, and jazz, poet Tony Whedon says he "can't wait to get to that computer every morning to see what's going to happen." Join Peter and Orlando as they explore Blue Ray, a collection of poems by Tony Whedon of Darien, Ga.