Section Branding

Header Content

Fostering Teaching Efficiency Through Teacher Leadership

Primary Content

In many businesses, “efficiency” is a top goal. In work with students, a focus on efficiency may sound cold—but take a look at all the work I must do before I can even begin instruction in my classroom:

Take attendance; grade papers; give meaningful feedback on assignments; collect assignments; implement educational technology; handle discipline concerns; provide remediation for struggling students.

Even as a 24-year teacher with the experience and ability to intuit the specific needs of a class, I find it difficult to effectively execute all these tasks efficiently enough to create more instructional time.

And gaining any time we can for instruction is crucial at any school, but especially at ones like mine—where nearly all students come from economically challenged homes.

I think we’ve found a way. Beginning in 2016, I became an Opportunity Culture expanded-impact teacher (EIT), in which I teach more students than usual—40 per class instead of 25. EITs are selected for their prior record of success with student learning and are paid more (within regular school budgets); it’s an especially effective model for schools that are hard to staff.

Nonetheless, any time you add more students to any teacher’s roster can be daunting. At Banneker High, we address that by combining EITs with aspiring teachers. These are full-time teachers in their first or second year in the classroom, selected by the administrative team as a promising new teacher to work alongside the EIT. Now, with two people in the room, all of the menial daily tasks get shared by the EIT and aspiring teacher—meaning we can move more quickly into instruction, with the aspiring teacher learning on the job what it takes to be a great teacher.

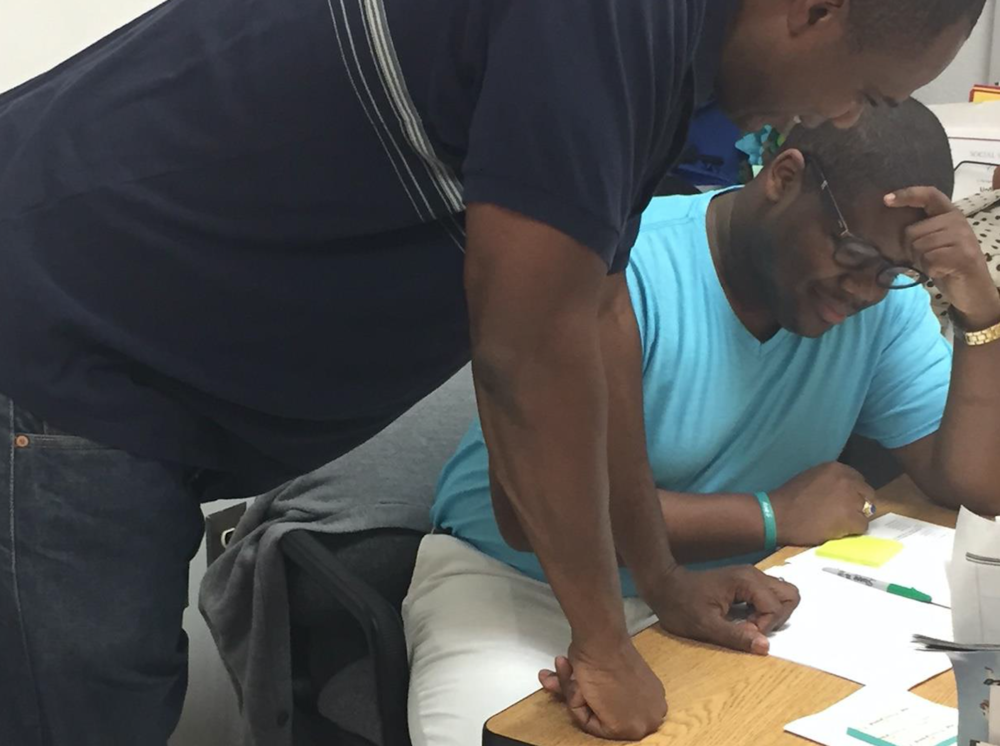

In the class block I teach each day with my aspiring teacher, we decided to split the “housekeeping duties.” each week. During our planning time, we would decide, for example, who would take roll, while the other collected homework. Then, if we timed it right, I could begin the “bell ringer” assignment or opening lesson as he distributed graded assignments and quietly gave individual feedback on them. What once might have taken 15 or 20 minutes now took five or six—allowing us to create more quality instructional time.

In our school, we see the need for a significant amount of structure within the classroom in order to deliver effective instruction. This model provides that structure and sets the tone for the class. Our students understood very quickly what the task at hand was because we were not bogged down with others unrelated to instruction.

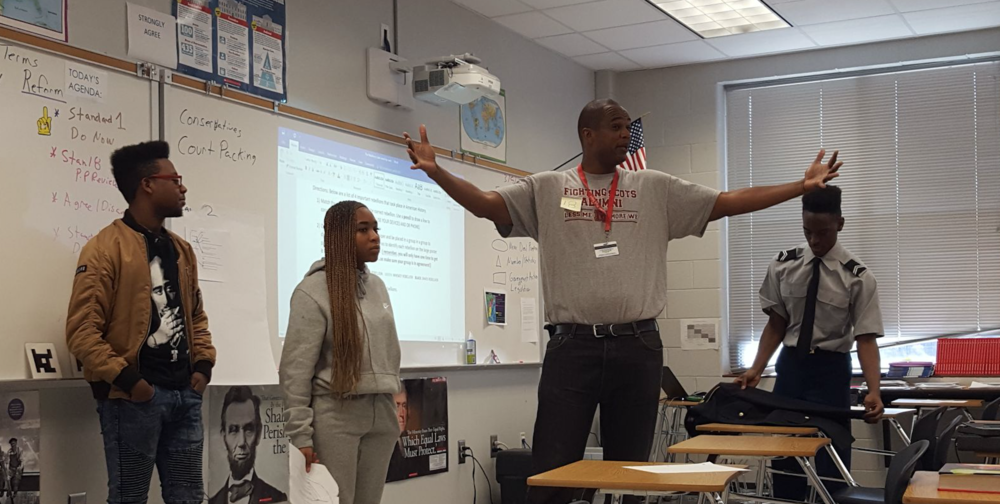

But it wasn’t just speeding through those tasks that mattered. Having an EIT-aspiring teacher combination had a pronounced impact on the instruction itself. Because I teach 40 students at a time now, I need more detailed and creative planning.

Our shared creativity was simply magical. I would present an idea for a lesson, and he would help figure out a way to make it more student-friendly and technologically efficient. For instance, during our unit on early America, he created a singalong lesson based on the Hamilton musical that truly engaged our students.

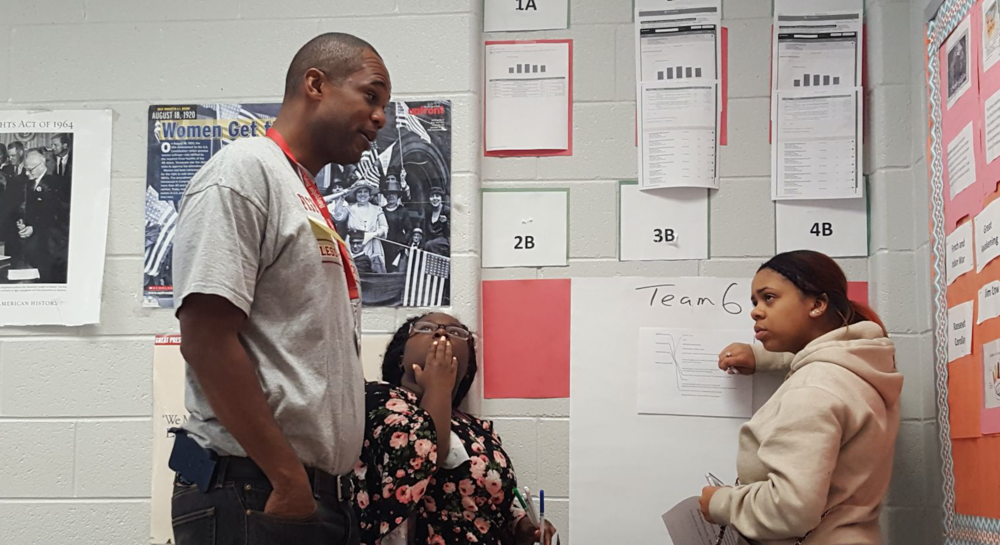

And having an additional set of eyes moving around the class helped with discipline and remediation. When one student had questions, we did not have to stop instruction just for him. One of us would simply go to him to explain. I don’t believe that students felt as though they were being watched or monitored when that happened; instead, they got the message that we were supporting their learning.

So it feels good—but ultimately, the EIT model will be judged by student progress and growth. In the words of Mark Twain, “Figures don’t lie.” My U.S. history students saw a 13 percent improvement in those scoring a 2 or higher on the state history test from my pre-EIT class, and 71 percent of them passed, versus an average of 66 percent in my other classes. For our student population, that is a significant gain. Notably, the class with the highest scores had the most students. I am clear that my aspiring teacher played a leading role in this progress for this specific class.

And the benefits go beyond one year’s worth of students. Keeping teachers in hard-to-staff schools is a goal of Opportunity Culture models like these—and because my aspiring teacher and I formed a bond of trust and professional development, he chose to stay at Banneker this year as a regular classroom teacher.

He and I had some very difficult but necessary conversations last year that were essential to his professional growth. I even had the opportunity to attend his ordination ceremony when he became a youth pastor in his church. On a daily basis, he saw that effective instruction in a disciplined environment was indeed possible when we used certain strategies. Our Opportunity Culture made him feel supported and part of a team. He also saw my shortcomings, and the times I did not have all of the answers. He truly understood that effective instruction is an evolutionary process for every teacher.

In my educational career, I have never been a part of a more thoughtful, practical, and effective classroom model than this. I have reached the twilight of my years in the classroom and feel the need to give back and share what I have learned. I think of the educational profession as a coral reef that adds on more and more to its structure every year—and working in this Opportunity Culture model has played the most significant role in helping me to accomplish my goal of helping teachers new to the profession achieve a level of excellence that we all aspire to reach.