Section Branding

Header Content

From 'Empty' To 'Satisfied': Author Traces A Hunger That Food Can't Fix

Primary Content

Author Susan Burton says food has been the site of her anxieties for as long as she can remember. For decades the editor at This American Life struggled with eating disorders.

Through therapy, Burton connected her disordered eating to her parents' divorce and not getting emotional needs met. She says that one of the reasons she was so preoccupied with food was that she was hungry all the time: "Hunger was something that I believed protected me and gave me power," she says.

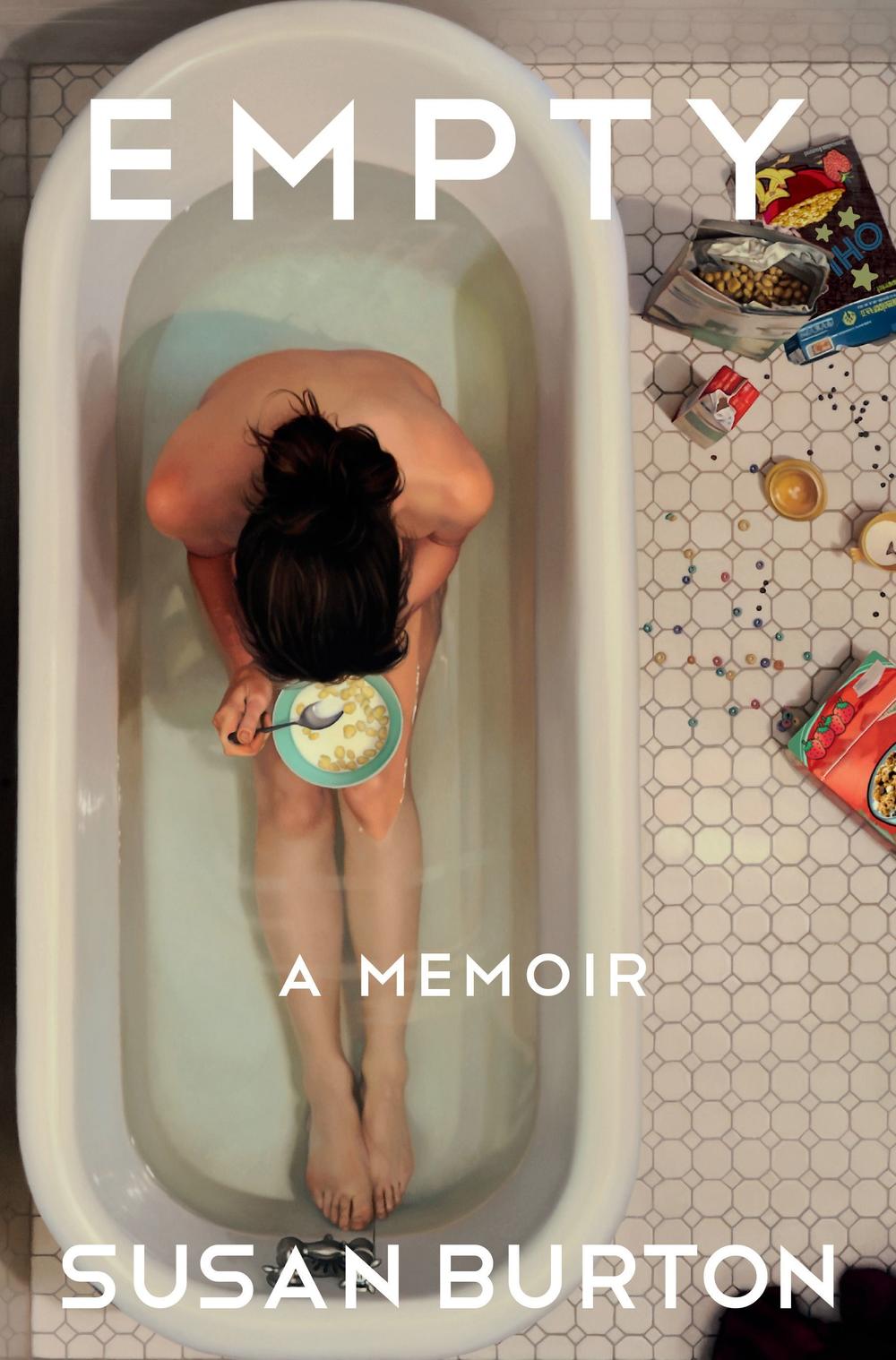

Burton writes about her experiences with anorexia and compulsive eating in the new memoir Empty. She says the title of the book was inspired by the feeling she chased for so many years.

"I loved the feeling of my body hollow, like a straw you could blow through," she says. "Now I understand that emptiness didn't protect me. It limited me. ... It was something that I thought would expand my life, but instead it ended up restricting it."

Burton says that she continues to work to overcome her eating disorders — including opening up for the first time about bingeing: "Anorexia was something that was visible to the people around me. So there was sort of no way of keeping it a secret. And bingeing, for me, it just happened to be where my shame was located."

Burton says her current relationship with food is better than it has been in a long time. "It takes a long time to learn to eat intuitively, to learn to recognize the body's cues," she says. "I eat more than I used to. I like the feeling of being satisfied."

Interview Highlights

On what binge eating was like

I think that a lot of people don't know what binge eating is. It's eating a large amount of food at once, more than most people would typically eat, afterwards feeling deep distress and self-loathing, and having a feeling of being out of control. It's a compulsive thing. You want to stop and you can't. ...

I'll give you an example of what it looked like for me: This is when I'm 17. I'm driving home from a concert with my best friend Jules, and I start the story in the car rather than in the kitchen, because an eating disorder is about so much more than food. An eating disorder is a way to cope with pain, or to cope with emotional needs that aren't being met. And I always wanted more from my friendship with Jules. I wanted to commune with her. I wanted kind of like this merger of souls.

And I often left encounters with her feeling deflated by not getting this — and that night was no exception. I dropped her off. I turned the corner. Started driving home. And almost immediately I was chanting to myself, "I'm going to go inside. Hang my key. Go straight upstairs. Go inside. Hang my key. Go straight upstairs." Meaning that I was going to circumvent the kitchen, because if I went to the kitchen, surely I would binge. I pulled into my driveway, went inside, hung my key. But instead of going straight upstairs, I went straight into the kitchen, where I started bingeing.

There was always a lot of ferocity in aggression in it for me, which was part of its power. I went to the freezer. I bit into a cookie, worried I chipped my tooth, but I kept going. The need to keep going was paramount because as long as I was bingeing, I didn't have to think. I didn't have to think about any loss or pain or wanting or yearning. That night I kept eating, like so many nights. I [ate] the foods that my mother bought. I [ate] granola with corn chips, string cheese. I ate until I felt uncomfortably sick. I went upstairs, didn't wash my face, brush my teeth, just got into bed and wanted to hide from what I'd done.

On her mother complaining about having a "potbelly"

All of the women in my family were fixated on their stomachs. For years, the first thing I checked in the morning when I got out of my bed was my stomach, whether it was flat or out or in. Certainly I internalized a message that being thin mattered. She wasn't the only one offering this message in our family. My grandmother once exulted, "I'm so glad I have thin grandchildren." It became a joke, but it was sort of a feeling that we all shared. My father was obsessed with this 1970s bestseller called Fit or Fat. So there's definitely a message in my family that appearance and size mattered.

On how Burton's grandmother weighed herself while she was dying

The moment when that happened, I was sitting beside her. I was 37 or 38 years old. I understood what it was to want to get on that scale and look at the number and stand there shrunken and triumphant. I was sitting beside her bed, and I was particularly thin then, and I felt it was because of my thinness that I could be there and emotionally available and experiencing these last days that I would ever spend with her, which now strikes me also as sad and ridiculous. Like my thinness wasn't making me available. It was limiting me. But at the same time, I was sitting at her bed, I was sitting there with a stack of her cookbooks, and my grandmother was a wonderful cook. And the cookbooks, all the recipes were marked up with her notes. And I was talking to her about all these things that she'd made. And it was very emotional and rich, and there were things I wanted to make for myself. And there was always this dichotomy in our family between taking real pleasure in food and being vigilant about it — and my grandmother is the one we sort of all learned that from.

On Burton's mother hiding her drinking while Burton hid her binge eating

I think it had a really big impact. ... There was a model for hiding. ... My mother was drinking, and I didn't, in those years, connect her addiction to alcohol with my addiction to food. Although I now do see them as connected. It could just as easily for me have been one substance over another. But the thing I was acutely attuned to was that we were both living these secret lives. So, for example, as a teenager, I would be upstairs in my room doing homework and she would be downstairs in the kitchen cleaning, correcting papers — she was a teacher — and she'd be drinking. And I would be upstairs in my room just seething and edgy and hating her, hating her not because she was drinking, but because she was in the kitchen, and I wanted to get into the kitchen so that I could binge. ... I was very conscious that we were both hiding out in the kitchen. We were both hiding out in the same place. I felt our secret lives very viscerally.

On how she relates to eating now, having spent the last two decades on the borderline of anorexia

When I was hungry all the time, I had headaches. I was often exhausted. I was often organizing my life around needing to come home and eat or needing to eat a certain thing at a certain time. And I'm letting go of those rituals. And with an eating disorder, food comes to stand in for relationships with people. And as my fixation on food dissipates, I am far more interested in relatedness with others. And that is one [benefit], in addition to the health benefits of dismantling an eating disorder [and] the physical health benefits of dismantling an eating disorder, there are social and emotional benefits, too.

Sam Briger and Thea Chaloner produced and edited the audio of this interview. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Deborah Franklin adapted it for the Web.

Copyright 2020 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.