Section Branding

Header Content

No Reading, No Peace: The Power Of Black Stories Out Loud

Primary Content

When I was a kid, my brother, sister, and I came to the dinner table prepared to do three things: Bless the food, eat, and share a story. We grew up in a family where the oral tradition was woven into the strands of our everyday lives. Mom was an English teacher. Dad, a grass-roots civil rights organizer who worked in public policy, was a gifted, charismatic storyteller. He didn't hold back when it came to sharing narratives about the dignity of Black people and the struggles we faced and transcended.

Both of my parents were voracious readers who understood the importance of taking books off their shelves and reading them aloud. My folks knew that the difference between just owning a book and experiencing its power stems from the oral tradition that is core to African American life and culture. One of the very first books Mom and Dad read aloud to me was The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats, the first mainstream book to feature a child of color as the central character.

Though Keats was white, his depiction of young Peter, the effervescent boy who goes out in the snow, was inspired by the neighbors and friends in his Brooklyn neighborhood. Keats was a firm believer in celebrating people of color in stories for children. His book was groundbreaking, and a bold step toward progress.

Up to that point, few children's books were set in urban places like the inner-city neighborhood where I was born. And not many celebrated the everyday lives and experiences of Black kids. Each time my parents read the part of the story when Peter returns home after his romp in the snow — He told his mother all about his adventures while she took off his wet socks – warmth filled every part of me. The fact that The Snowy Day has stood the test of time for more than 50 years is a testament to its read-aloud staying power.

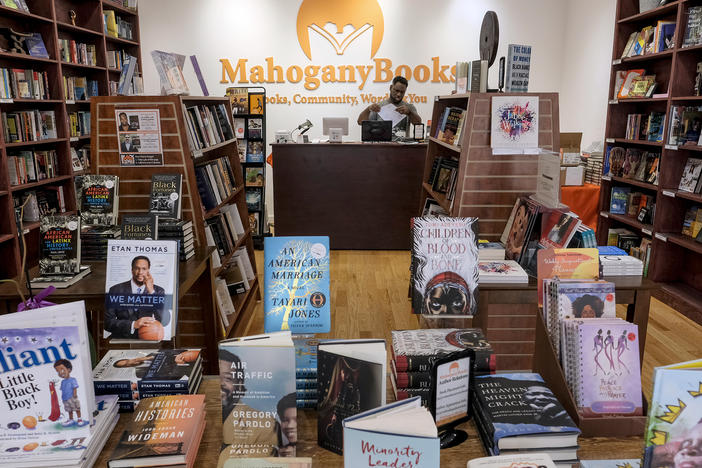

As the world embarks on a renewed interest in Blackness, I applaud those who are taking special care to include more Black books in their homes, schools, and libraries. But to ignite those stories, and to bring the realities of racism, Black history, and social progress into the consciousness of kids, young readers need to hear these stories spoken. And they need to hear them often. It's one thing to buy Black books. But sharing them is what truly brings these important stories to life. Reading aloud is the turn-key difference in ensuring that children's books featuring Black and brown characters and experiences have relevance and staying power.

Any teacher will tell you that repetition is a key to learning. Stories stick when they're shared repeatedly. These stories reach deep into kids' hearts where truth lives, and where our children are coming to understand anti-racism and racial harmony.

If we want these stories to give our kids the agency they need to make changes in our world, we need to ignite and invite. To me, books are like lightbulbs — they shine brightest when we turn them on. We bring power to stories by telling them and encouraging young people to talk to us about what they're reading. Similarly, not reading aloud to kids is like giving them lightbulbs that are only partially lit.

According to a report from the publisher Scholastic (where I am an editor and vice president), 85% of children ask questions during read-alouds by the time they're eight years old. Taking a closer look at families' habits during read-aloud time, the report's research reveals that reading aloud with a child is a highly interactive experience — it's a partnership. Parents and children alike say they love read-aloud time because it is a special time with each other.

Adding to this, the American Academy of Pediatrics has released guidelines encouraging parents to read to their children beginning at birth, saying it enhances brain development, language, and literacy skills. Simply put, reading aloud is good for your child's health.

We all want wellness. I believe racism is a disease, and that healing can begin by reading to the kids in our lives, starting with children of the youngest ages. While writing my latest novel Loretta Little Looks Back: Three Voices Go Tell It, the energy of read-alouds was top-of-mind as I crafted the book's narrative. The story features three characters, Loretta, Roly, and Aggie B., members of the Little family, who each present first-person accounts of growing up in the Jim Crow South. Their separate stories — beginning in a sharecropping cotton field in 1927, and ending with the presidential election of 1968 — span three generations fighting for racial equality. The narratives are a mix of spoken-word poems, folk myths, gospel rhythms and blues influences, presented through storytelling's oral tradition, in a series of "go-tell-its" that paint a portrait of America's struggle for civil rights as seen through the eyes of kids who are experiencing it. As a read-aloud, the stories are interactive. It's my hope that young readers will feel the ugly truths of living in a society riddled with bigotry, and will come to understand how the racial realities of the past affect inequality today.

Sharing the book with classrooms has been a keen reminder that reading aloud is a two-way street. When I invite kids to read select passages with me, they're empowered to speak up about their beliefs. Each time they hear the words of a story coming out of their own mouths, they're emboldened to keep reading. These same kids are more inclined to seek out more books, and they're encouraged to share the books they love with their friends. That's what activism is. A movement begins when a passionate person gathers like-minded people and says, "Let's do this together."

Reading Black books aloud is how a true revolution can begin for stories that illuminate Black and brown protagonists, themes, and depictions. As an author and parent, I've discovered that my own children learn best when they connect content to meaning. When they feel what they're reading, they enjoy it to a greater degree, and retain it more readily.

As my parents taught me, kids hear what they hear — and they also hear what's not said. We teach by what we express, and by what we don't. Before feeling proud about your growing library of African American books, please take the "read-aloud litmus test." It's a simple inquiry: How many of these books have I read to the kids in my life, and do I share Black books on a consistent basis?

In the recent public outcries surrounding Black Lives Matter, one of the key components to the campaign for justice has been an added affirmation to acknowledge the men, women, and children who have been victims of police brutality — Say Their Names. Reading aloud let us do this. When we share books and stories with kids, we say what needs to be expressed. Kids depend on us to open the door to important conversations, and to invite them to pull up a chair so that they can speak to us about what's on their minds. Talking about race can only begin with talking about race. Read-alouds spark necessary dialogues and let kids tell us what they think, how they feel, and what they plan to do to make the world a better place for everyone.

Andrea Davis Pinkney is the New York Times bestselling and award-winning author of numerous books for young readers, a vice president at Scholastic and a past spokesperson for Read Aloud 15 Minutes and the Read-Aloud 21 Day Challenge.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content