Section Branding

Header Content

What You Need To Know: Racial Disparities In Coronavirus Infections

Primary Content

Georgia Public Broadcasting’s new series What You Need To Know: Coronavirus provides succinct, fact-based information to help you get through the coronavirus pandemic with your health and sanity intact.

Dr. Joseph Hobbs, chair of the Department of Family Medicine at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, talks with Grant Blankenship about the disproportionately higher number of coronavirus infections and deaths among African American communities in Georgia as well as in other states and communities across the country.

So, yeah, as I said, you've studied how disparities in healthcare flow from racism. Now, with coronavirus, we're talking a lot about these underlying conditions being dangerous to people when they're infected by the coronavirus. How are racism that leads to unequal health care access and these underlying conditions related to each other in the South?

Well, I think that in a sense, what we're seeing here in the South is not a lot different than what we're seeing in parts of the north and the West Coast, too, as well. There's a big, huge gap between the chronic disease process that African Americans have and other groups of color have when compared to the population in general. A lot of that is based upon socio-economic factors.

We know that common diseases that we see that are disproportionately prevalent in the African American community and already create worse outcomes with the period to the population as a whole. These are the very same conditions that quite frankly, predict for poorer outcomes when people have COVID-19 infections. Those are hypertension, diabetes, also heart disease, severe renal failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. And it goes on and on and on the sorts of things that are very commonplace in the African American community because this is a disproportionate disease burden that they already bear.

Health care disparities have been with us. Even looking at universal healthcare coverage and things of this nature has been something that we grappled with because if the way that you get access to healthcare is based upon your ability to pay for it, that might sound like a good way to look at health care. The problem is, is that what people fail to recognize is that if that's a segment of my society that's out there in the workforce, out there in the schools, out there in the public and if they are uniquely ill..... someone's going to pay the cost for that.

If they don't have access to healthcare, it's either going to be us paying for it when those people come in with acute urgencies. So, all of us are impacted by this, which tells us that the whole idea of racial healthcare disparities is not just an issue for the minority community. This is an issue for all of us because the health of America depends upon creating equity in access to health care services for everyone.

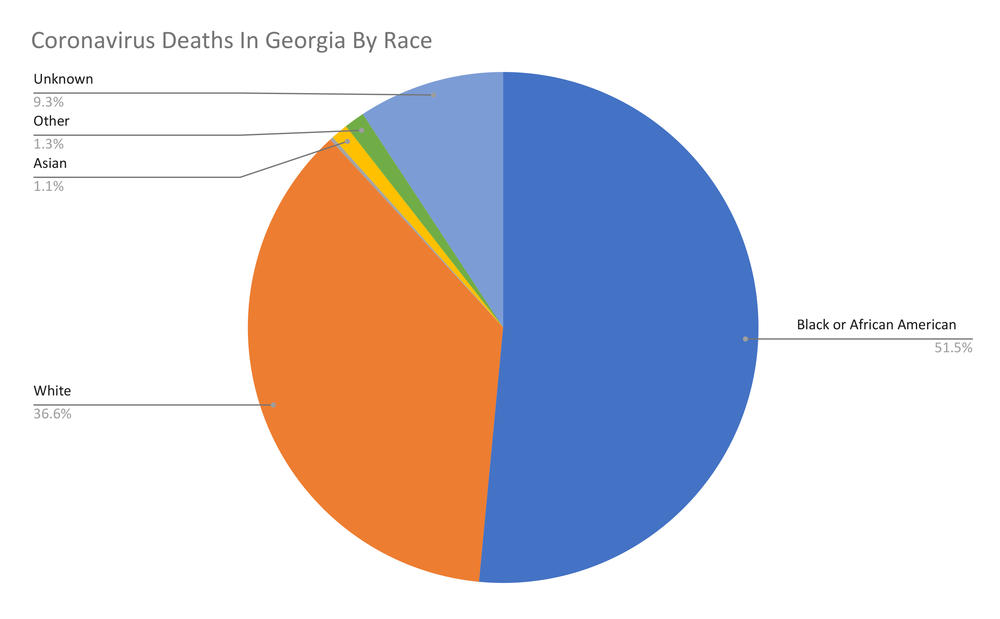

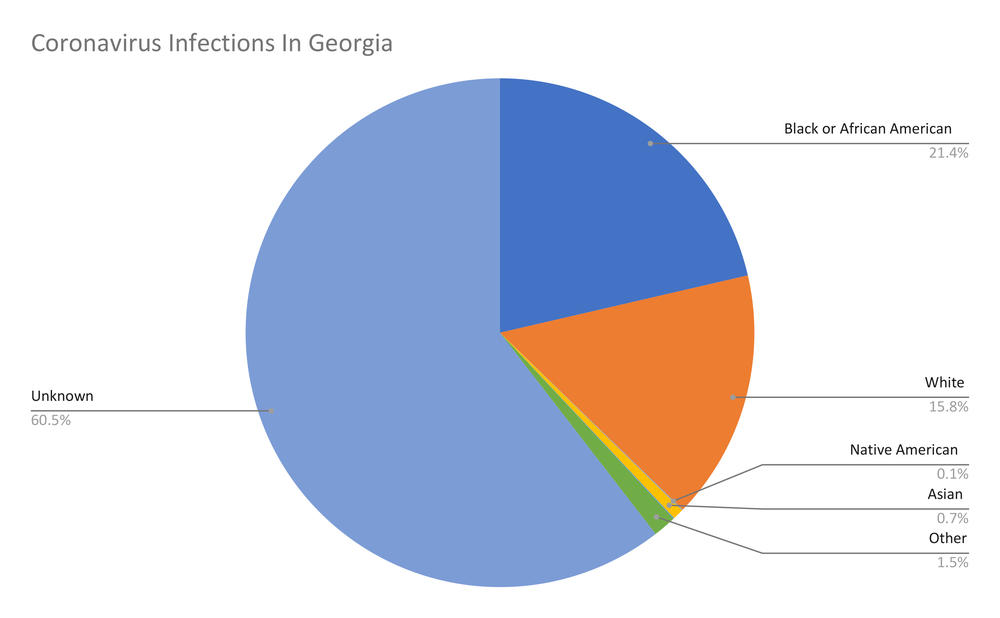

And as I said at the top of this conversation, Georgia really doesn't have a very good idea of exactly how disproportionately this disease is affecting Georgians. They're not keeping very good numbers on like 63% of the people infected. We don't know whether they're white, black or whatever. Why does that matter in the thick of a pandemic that we know this fact?

Well, it tells you where you need to put your resources. It tells you where you need to do testing, where you need to do case follow up to try to find out where the individuals have been, who live at contact with things like this because it just tells you where you need to put those resources to begin to get a sense of where the infectious process is. To begin the work of containment. Not knowing that is very, very difficult a place to start.

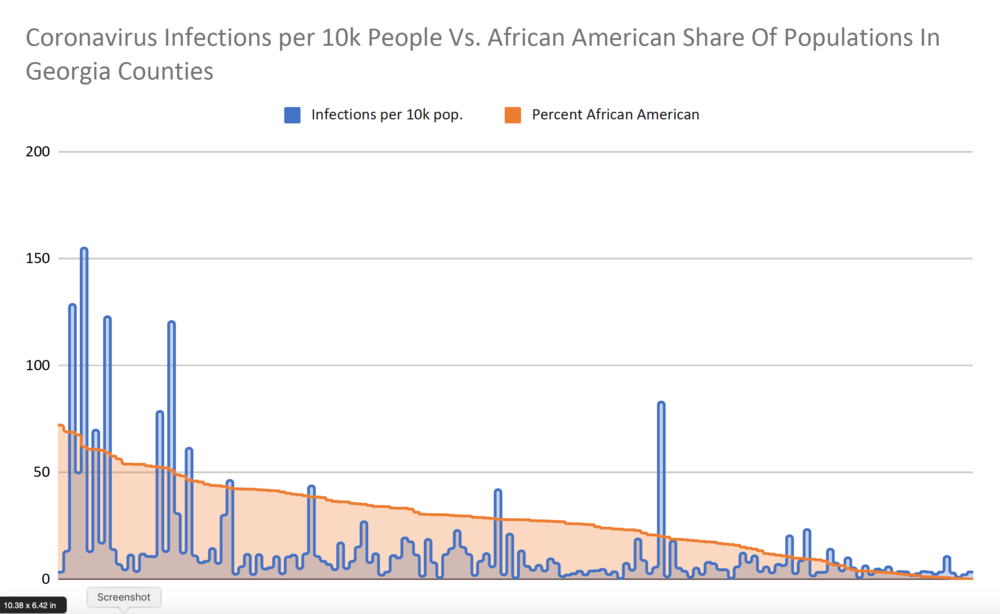

I spotted last week, too, that the state started actually reporting some of these racial demographics when it comes to deaths and infections. In the meantime, I've been bodging together census data of what proportion of Georgia counties are African American with just the raw infection rates.

And you can see the correlation at the county level pretty easily without the Georgia Department of Health's help. But I guess my question is, is that county-level knowledge... just being able to go and say, yes, people in this county, which is predominantly African American or more likely to be infected....Is that enough knowledge to begin this sort of prioritization that you're talking about of resources during an epidemic response? Or do we need something more fine-grained in particular to really be effective?

I think that we need something more refined because if you look at some of these counties, I would wonder whether or not the fact that they don't have a case or they have single-digit cases is because you haven't looked. And the point being is that what we need is that we need surveillance, not necessarily surveillance of the entire population, but enough surveillance for us to begin to get a sense of the incident of people getting infected with this. Because I think if you're able to get that sort of information, make sure that you're getting the information based upon gender and ethnicity.

At the same time, you're going to have information that's going to tell you a lot more about where this disease is. And because even in those settings, if you have a lot of disease processes, that these people may not be symptomatic with the disease, they are particular carriers of the process as well. You've got to be able to look at the population in a larger sense to that, to be able to find the diseases. And did that contain the disease in that particular area?

And therefore, if the disease is there, the risk of those persons having bad outcomes and even deaths are far higher and none of those circumstances that you'd want to put your resources there. If you had nothing else to guide you in knowing where those resources would be best applied.

As an event passes in the night, it becomes distant in our memory. As humans, we are prone to make the same error again. I would hope that something like this has burned itself in our consciousness to know that our new normal has to be something different. And in the way that we look at health and disease has to be something that is looked at more universal because your health affects me, my health affects you.

And so therefore, it's going to be important for us to make sure that we create systems within our country that do not permit these sorts of disparities to exist because these disparities can have impact on all of us from a health standpoint, from an economic standpoint. I mean, all of those things are out there. So my fear is that we'll forget.