Section Branding

Header Content

Illness Caused By Breast Implants, Georgia Women, Plastic Surgeons Tell FDA

Primary Content

Jennifer Butler lost part of her right breast after she was diagnosed with malignant melanoma. She was 22. A year later, she got silicone breast implants. She said she remembers doctors telling her — pushing her — toward silicone implants, describing them in 2009 as “new and improved” after having been taken off the market previously and now returned as safer than ever.

She's one of many women and doctors in Georgia who say breast implants caused systemic illness.

By the time Butler was 27, one of the implants had torn the soft tissue on the right side, where she’d had cancer, and another surgeon had to go back and rebuild the support structure for her breasts. Butler loved the idea of having “a built-in Wonderbra,” but within weeks of the surgery, she started feeling sick. The first thing her doctor suggested was that the malignant melanoma had spread to her brain.

Many Georgia women who got breast implants started feeling sick shortly afterward and, now, those women are coming forward to tell their doctors, the public and the Food and Drug Administration about “breast implant illness,” which they describe as a multitude of symptoms stemming from having either silicone or saline breast implants.

Feeling sick

Marisa Lawrence is a plastic surgeon based in the metro Atlanta area. She said breast cancer patients make up 10 to 20 percent of her practice. Other patients, such as Lauren Caccavone, have congenital defects such as Poland syndrome. When she was 23, in 2012, she saw Lawrence for help.

When Caccavone called Lawrence to complain of strange symptoms after the surgery, Lawrence thought the issue might have been muscular-skeletal strain or, possibly, inflammation.

“I went back to my surgeon with new, severe neck and shoulder pain,” Caccavone said. “The onset of the pain started within a month of getting the implant.”

A few months afterward, Caccavone was bedridden. She had been diagnosed with Epstein-Barr virus, an infection that causes mononucleosis, for the second time in her life. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention say it’s rare for cases of the virus to reactivate.

Caccavone, Butler and other local women told GPB News they had to advocate for themselves when they started feeling sick and couldn’t find answers.

“I became very sensitive to the sun and started getting night sweats,” Caccavone said. “I had chronic fevers, swollen lymph nodes and unexplainable rashes.

In addition to worsening pain, Caccavone said she started getting chronic nerve pain in her feet, was gaining weight despite a healthy lifestyle and even noticed her hair and nails were thinning.

“In 2014, I went to an infectious disease doctor and literally had everything under the sun tested only to come back negative,” she said. “No rheumatoid arthritis. No Lyme. No Lupus. In 2015, I was diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome by a specialist.”

Around New Year's Eve last year, she lost a pregnancy.

“I was having vision disturbances; I was having horrible headaches and like brain zaps,” Caccavone said. “And then, ultimately, lost the baby. And that really pushed me to do more research because, according to bloodwork, everything's fine.”

Feeling devastated and desperate for answers, Caccavone turned to Google. By August, she scheduled her explantation surgery, the term patients and doctors are using to describe having their implants removed, with Lawrence. A month later, the MD Anderson Cancer Center released the largest-ever study of silicone breast implants associated with rare diseases.

Seeking Answers

Caccavone told her story to the FDA last week ahead of a March 25 and 26 meeting at which breast implant illness will be discussed, according to the agenda.

“I began doing a lot of research on my own and I kept stumbling across 'breast implant illness' articles, Facebook groups, and Youtube videos,” Caccavone told the FDA. “I was shocked at how many women had shared stories that were extremely similar to what I was going through. They claimed that the body rejects their implant and the immune system tries to attack the sack. They develop autoimmune symptoms, EBV, and CFS/fibromyalgia. They were saying the pain and symptoms were going away after explant and detox.”

Butler’s similar experience and research led her to a book by another Atlanta-based plastic surgeon, Susan Kolb.

When a blogger sent Butler a post about having her breast implants removed, everything clicked and Butler followed a recommendation to buy Kolb’s book, “The Naked Truth About Breast Implants: From Harm to Healing.”

“I ordered it, avoided it for a year or so, and finally read it,” Butler said. “And that's when, after cancelling the appointment a few times, I finally went it. I mean, I had to get to the end of my rope to finally go in and do the surgery because I did not want to lose my boobs.”

Kolb explanted Butler’s implants in May of last year. Almost immediately, Butler felt better.

Patients have suffered from autoimmune diseases, chemical toxicity and diseases due to mold biotoxin illness, especially in patients with saline implants, Kolb said.

“Many patients have problems with silicone, chemical, biotoxin and heavy metal toxicities along with co-occurring infections of yeast, mold, intracellular infections, viruses, parasites, and bacterial chest wall infections,” Kolb said.

After speaking with Caccavone about her experiences and the research Caccavone began turning up, Lawrence said she began to see a trend in the number of patients reporting systemic symptoms they believed were caused by both silicone and implants. That was around June 2018.

The existing medical literature did not support a link between implants and illness, but Lawrence said she could see these women were sick. So, she began her own research, asking women their histories with implants and possibly related symptoms. Lawrence gathered data on doctors, types of implants and manufacturers.

“I collected over 200 of these questionnaires and then started researching them,” Lawrence said. “Then, as I was explanting patients, if I could get insurance to cover it, I would send the capsule, the scar tissue around the breast implants, for pathology to see if there was anything abnormal in the cellular structure.”

Lawrence wanted to know, specifically, whether an infection was triggering the women’s immune systems. At a meeting of the American Society for Aesthetics, the surgery arm of the American Society of Plastic Surgery, in Chicago last October, a task force was developed to conduct more research.

Now, Lawrence’s research is being funded.

“I'm very excited about that because I want to be able to send these specimens for advanced DNA evaluation of capsule or tissue,” she said. “Some of my patients have talked about having metal testing; I'd love to be able to do that. I mean, we acknowledge that we need to do a lot more research on this illness.”

Feeling Better

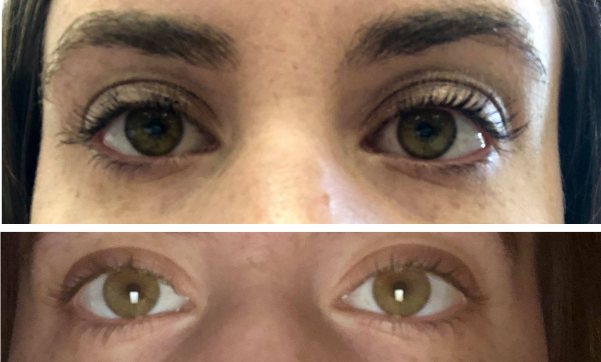

Caccavone knew tens of thousands of women in a breast implant illness group on Facebook recommended taking before and after pictures — of eyes.

“The picture of my eyes right before was like dark circles under them, all pink in the corners and puffy,” Caccavone said. “They look kind of gray, and almost like glazed-over, sick eyes.”

The after picture showed no dark circles and crisp, bright-white sclera. She said the inflammation immediately cleared up and her pain disappeared. Puffiness in her face went down just as quickly.

When Caccavone exclaimed to the nurses that her vision was restored, they reminded her, “Oh, you’re on a lot of drugs, honey,” but Lawrence came in and assured Caccavone she was not the first patient to say her vision was better after removing breast implants.

By early March, three and a half months after her implants were removed, Caccavone said her hair had grown 7 inches.

“My eyelashes are back to normal; my nails are stronger,” she said.

Butler said her skin had turned yellowish and, despite being 30 years old, she was winded walking up a flight of stairs before her surgery to remove her silicone breast implants. Within three days, her color was back to its normal pink hue, she said, and she walked a mile within two weeks of her surgery.

“I just felt like I was me again,” Butler said. “The joint pain completely stopped; the stomach issues and the food allergies I had completely stopped. The brain fog completely stopped. The fuzzy vision stopped. All of it.”

Tellling the FDA

Caccavone sent her story to the FDA March 3. Her doctor hopes to speak during the March 25 meeting as well.

Lawrence said she wants to do more research and hopes to learn more about the metals involved not with the chemical in the implants, but with the capsules that hold the implants in place.

The bags themselves don’t have metals, but Caccavone and Lawrence learned the capsule can. The one Caccavone used had platinum, lead and nickel in the capsule, she said, and Caccavone said she cannot even wear nickel earrings without getting a reaction.

“Perhaps, these women have an allergic predisposition towards even the slightest amount of these metals,” Lawrence said.

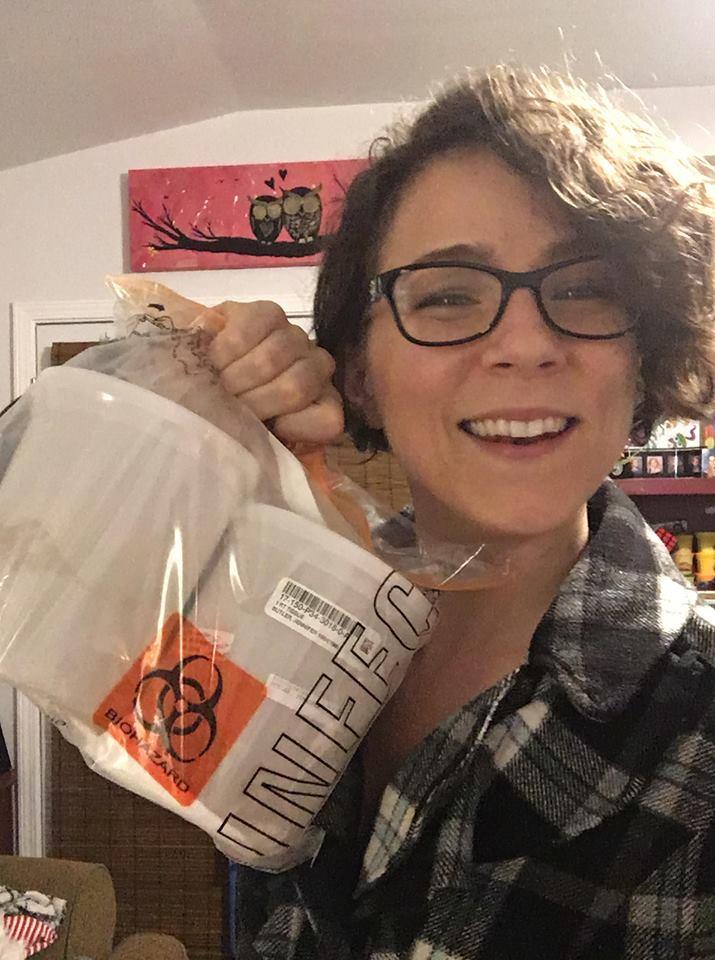

When Caccavone wanted to get her implant back from the manufacturer, she had to fight.

“Allergan actually would’ve paid for part of my surgery if I would have agreed to send them the implant for them to ‘study.’ I did not agree to that in case I need it as evidence for any type of potential lawsuit, and, honestly, just because I don’t trust them.”

Lawrence made a special request for the pathology department to hold it for Caccavone, and she picked it up from there. For a while, Caccavone said “Northside Hospital was not going to give it back even though it was technically my property.”

After being told by two of the implant companies that the components of the implant silicone shell was "proprietary information," Lawrence said she obtained the "Summary of Safety and Effectiveness Data" from the FDA's website, which provided her with the information. The low concentrations of the metals have been reviewed by a toxicologist who has studied breast implants for 29 years, Lawrence said, and he did not believe they were significant in causing breast implant illness.Dr. Marisa Lawrence discusses the importance of communication and what she tells women who ask about breast implants and related illness.

A spokeswoman for Allergan sent a statement to GPB without addressing Caccavone's concerns.

“Allergan looks forward to the upcoming FDA Advisory Committee Meeting where we can continue to participate in the science-based public dialogue on a range of topics concerning the benefit/risk profile of breast implants,” the statement said.

The capsule from around Caccavone’s implant also showed bacteria and biofilm, and a pathology report showed she still has chronic reactive inflammation that she continues to try to detox from her body.

Lawrence said she plans to attend the FDA’s meeting later this month. Some of the issues to be addressed include the anaplastic large-cell lymphoma that is associated with textured implants and breast implant illness, which they are calling systemic symptoms with breast implants.

“They're looking at MRI surveillance of implants; they're looking at the use of biologic mesh with implant surgery,” Lawrence said. “They want to know about breast implant registries. They want to know about using real-world data to make decisions on breast implants. So, they've got a very hardy agenda and breast implant illness is one of the seven topics that they're going to be addressing.”