Section Branding

Header Content

How Does Georgia's Election System Work?

Primary Content

On a recent sunny Monday, joggers on their morning stroll in Fayetteville's McCurry Park might have been surprised to hear thumps, clicks and whirrs coming from the elections trailer next to the parking lot.

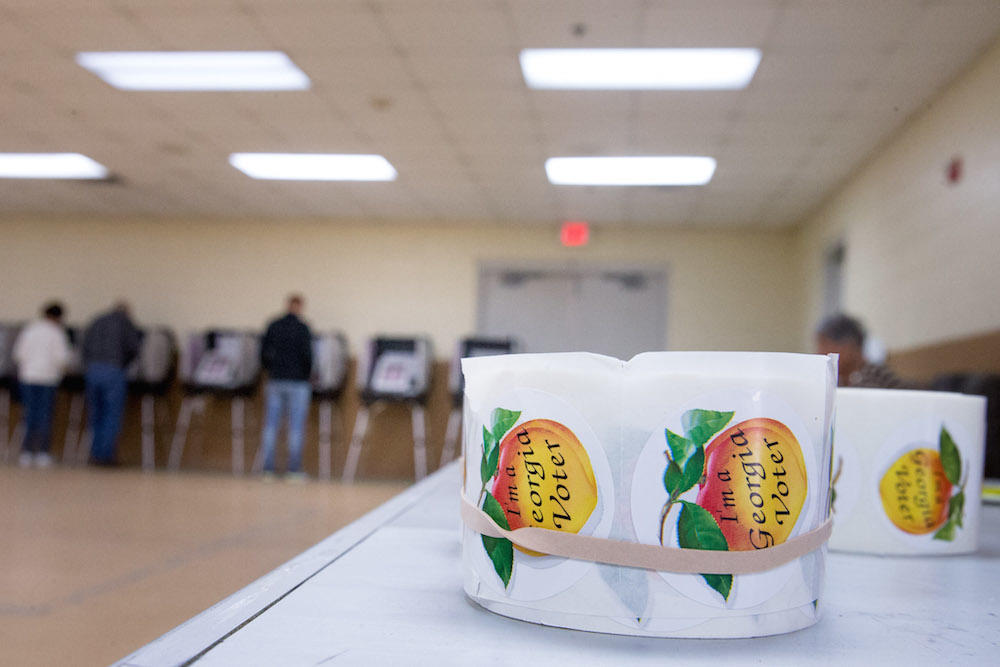

Over the course of several days, that trailer 20 miles south of Atlanta was where officials tested close to 300 voting machines to ensure they operated smoothly and accurately. Those machines would go out to 36 precincts across the county for the Nov. 6 midterm election.GPB's Stephen Fowler examines how Georgia's election system works, from the time a ballot is created until the last vote is counted and certified.

The security of those touchscreen, direct-recording, electronic voting machines is a hot topic currently. In September, a federal judge denied a request to move the midterm elections to paper ballots, citing a tight timeline that could be rife with confusion. Judge Amy Totenberg also said threats to the way the state’s elections operate are real, and problems with the current touchscreen system must be addressed in the near future.

But that’s just one piece of the larger election puzzle. So how exactly does an election in Georgia come together?

PREPARING THE BALLOTS

Running an election in Georgia starts months before the first ballot is cast and ends days after the last ballot is counted.

It’s a multi-step process that involves the secretary of state’s office, local elections officials in 159 counties and thousands of volunteer poll workers to execute, sometimes multiple times a year.

At the secretary of state’s office, the elections team gets to work as soon as candidates are set.

Elections Director for Georgia Chris Harvey said the first step his team takes is to create a “ballot image,” which is the layout of how the ballot looks.

“You take each county, and then you take the different ballot combinations, and you take the qualified candidates and you just start plugging them into the slots,” Harvey said.

That continues until every race, every question, and every candidate accounted for.

Harvey’s office created about 2,500 different versions of a ballot for this Nov. 6 election, with everything from the hotly-contested gubernatorial race between Democrat Stacey Abrams and Republican Secretary of State Brian Kemp to whether residents in Sandy Springs can purchase alcohol earlier on Sunday.

In Fulton County alone, there are 115 different ballot images that have to be created.

Once those digital files are created, the secretary of state’s office hand-delivers them to county elections officials, who have to verify they received the files and that all of the different ballots are correct.

In Fayette County, Floyd Jones is the elections director. Locally, his office has to decide how many voting machines go to each precinct, qualify local candidates for races and check those sample ballots for accuracy.

Once those steps are complete, the ballot images are downloaded from a secure Global Election Management Systems server onto memory cards for each voting machine.

TESTING THE MACHINES

In the Fayette County elections trailer, four black boxes are lined up on tables. They are the voting machines that will go to the Blackrock voting precinct in Fayetteville, and the first ones to be tested.

The machines are tied to specific precincts by serial numbers marked several times on and around the machine. Each memory card that has the different ballot combinations loaded are also tied to a specific precinct and tracked by serial numbers. Even the seals used to physically secure the machines before and after testing are marked on a list and identified by number.

All of these elements are inspected during a process called Logic and Accuracy testing, according to Fayette’s election director:

“What we're doing is we're taking the machine, and we're literally ensuring that it actually works,” Jones said. “Then we're uploading the new ballots into the machines so they can be prepared to roll out on Election Day.”

The process takes a few minutes. Everything from the ink in the printer to the click of the card reader undergoes scrutiny, and a sample tally is run to make sure the machine can register votes, and that what is registered lines up with the responses that someone pushes on the screen.

Once all 292 machines in Fayette are tested, Jones said the memory cards and the machines are sealed and prepared to be sent out for Election Day.

ELECTION DAY

By the time 7 a.m. rolls around on Tuesday, Nov. 6, the machines will be delivered, the seals will be broken and poll workers across the state will be ready for business.

Richard Barron is the elections director for Fulton County, which is the most populous in the state. He said the fastest way to make your way through the voting process is to have your driver’s license handy for poll workers to scan you in. As you check in, your information is loaded onto a yellow voter access card, using the same type of chip technology that is found on new credit cards.

“All the ballots for your county are available on the voting machine,” Barron said. “But when you push the card in, it will only activate the ballot that correlates to your residence.”

Once your finish making your selections, your vote is captured on the machine’s memory card, and the yellow card is returned to the poll worker. The same system that puts your information onto the voter access card also communicates with other polling locations, to keep people from attempting to vote at multiple precincts.

The polls close at 7 p.m., but the polling place will not shut down until the last person in line has voted. At that point, poll managers consolidate the vote tallies onto a single memory card, shut down and seal the voting machines, do paperwork and then drive results to a central location.

From there, precinct totals are uploaded to the state’s election-night reporting system, which shows results online for the public to see. State election rules require counties to upload three times throughout the night, and things like the speed of the poll worker, the length of the line when polls close and the distance that must be traveled to upload results can affect when they come in. In Fulton County, that part of the election definitely takes a while.

Barron said Fulton County spans nearly 75 miles from tip to tip, and it takes time for all 183 voting locations to be completed.

He said a relatively new “election night assistant” program should cut down reporting time, where county employees help break down the polling site while the poll manager focuses on consolidating the memory cards.

And this year, Fulton County will have law enforcement escort those poll workers and the memory cards with the votes from five check-in centers throughout the county to the main elections warehouse, thanks in part to an ongoing federal lawsuit that wants to force Georgia to use paper ballots for elections.

But Chris Harvey with the secretary of state’s office said the process isn’t over, even after candidates declare victory and the website says 100 percent reporting.

“Somebody conceding or the news calling something has zero effect on anything we do,” he said. “We still have to account for every ballot that's cast – and it doesn't end the morning after the election.”

There’s still some mailed-in absentee, military and overseas ballots that must be counted, plus provisional ballots cast on Election Day.

Harvey said counties have to certify their results by the Monday after the election, and the state has to certify within a week after that. After the election is certified, candidates can request a recount if there is an issue, and the process starts all over for anything headed to a runoff.

This could be one of the last times this process is used.

Seven different vendors have submitted options to replace Georgia’s voting machines and elections infrastructure as part of secretary of state Kemp’s Secure, Accessible and Fair Elections Commission.

Their goal is to have a new system in place for the 2020 presidential election.