Section Branding

Header Content

Sabal Trail Pipeline Plows Through Southwest Georgia, Local Opposition

Primary Content

James “Jeb” Bell’s 100 acres of land in Mitchell County is typical southwest Georgia: groves of spindly pines patch open fields, cicadas whine, gnats bite.

“This ain’t a whole great pile of land, but it’s ours, and it’s been ours for 30 years,” said Bell stepping out of his pickup truck on a recent morning.

He and his brother got the land in the 1980s from their mother, who bought it for them during a bout with cancer. She wanted to give her sons a place where they could eventually settle down and build homes.

As of late, those plans have changed.

Standing in a wide clearing, Bell pointed to a row of small flags that trace across the land. They mark the path the Sabal Trail Transmission will burrow through his property.

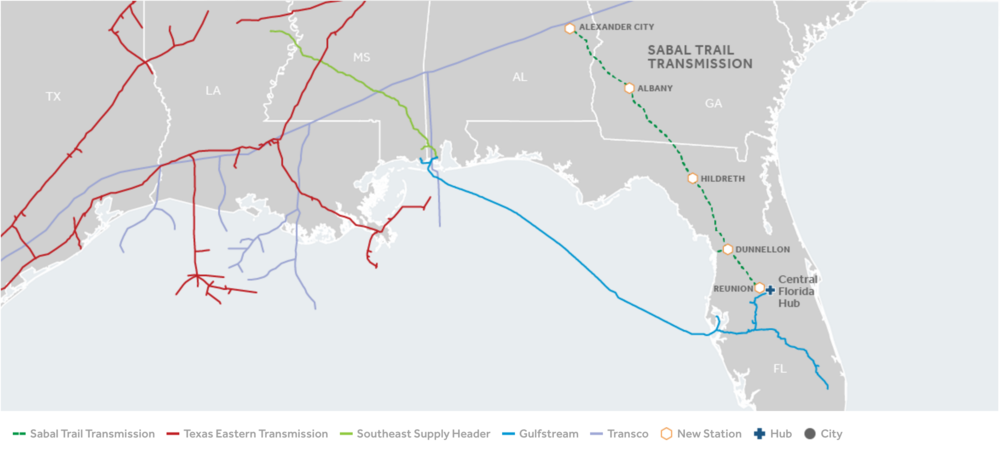

The 515-mile pipeline will originate in eastern Alabama, cut through southwest Georgia, and terminate in central Florida, where it will serve the needs of two local utilities there.

The project will cover about 160 miles in Georgia, but it won’t deliver gas to any of the state’s utilities when it comes online in 2017. The pipeline will include two taps in Georgia for possible future use, but, for now, no utility has any formal plans to use them.

Sabal Trail won’t be the first pipeline on the Bells’ land. Kinder Morgan’s Southern Natural Gas line already cuts through their property. But that project was completed before Jeb Bell’s time, and he’s not ready for another pipeline.

He’s been ready to fight the Sabal Trail project since he first heard about it in 2014. That’s when he received a letter from Spectra Energy, the company building the pipeline, informing him of the project.

“I wrote them a letter within days of getting their first letter that said: ‘Stay off my land. I do not want this pipeline on my land,’” Bell said.

Bell had a litany of concerns ranging from the safety of living near a three-foot wide, highly pressurized pipeline to the impact the project would have on the value of his property. He also had issues with a for-profit company using his land for their gain.

Spectra eventually filed an eminent domain lawsuit against the Bells to get the right of way they needed for the project. At the same time, the Bells sued the company for trespassing.

The Bells lost both cases. In the trespassing case, a judge ordered they pay $47,000 to cover Spectra’s legal fees.

“When you got something that big hanging over your head--you got a multi-billion dollar company that virtually has unlimited resources doing pretty much whatever they want to--it’s extremely stressful,” Bell said.

As of late, Bell isn’t the only person feeling that stress.

Minnie Jackson lives in Countryside Village, a mobile home park in Albany less than a mile from where Spectra plans to build its only compressor station along the pipeline in Georgia.

“This is a lovely area. It’s peaceful. This is a place here where you can raise your family,” she said.

Minnie Jackson on her concerns about the Sabal Trail pipeline and compressor station.

Jackson worries the compressor station’s gas-pressurization turbines and round-the-clock operations will disturb the quiet nature of her neighborhood. She’s also concerned about the health risks of living next to the facility.

“This is a quiet residence, but with this here coming, I’d rather go,” Jackson said.

However, leaving isn’t an option for her. Jackson said she lives on a fixed income and can’t afford a move. So, she’s been involved in small efforts of resistance–going to meetings, attending protests–but with little effect.

“That’s the message they sent: 'You can resist, but we’re going anyway,'” said Dougherty County Commissioner Harry James.

He represents Minnie Jackson’s district, which covers western portions of Albany. James said he’s felt powerless to stop the project, a feeling that’s compounded when he hears the concerns of his constituents.

“As a lawmaker, people assume that you have the power to do things you don’t have. That creates frustration,” he said.

Georgia lawmakers also tried to block the project. In March, they grappled with a bill that would have granted Spectra the rights-of-way over a number of state-owned waterways, like the environmentally-sensitive Chattahoochee and Flint rivers.

But the bill that passed did not grant Spectra those rights. State lawmakers weren’t convinced the project would benefit Georgia and worried it posed too much environmental risk.

So, Spectra sued the state of Georgia for those rights-of-way and won.

“I think there are some who are simply opposed to the project, and that won’t change,” said Spectra spokeswoman Andrea Grover. “But, for the most part, we’ve been able to work with the communities and the landowners.”

But any time it's faced opposition to the project at almost any level, Spectra’s had an ace up its sleeve: a permit from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, or FERC.

FERC reviews interstate energy projects like pipelines based on factors like market need and environmental impact. After a review of more than a year, FERC approved the Sabal Trail pipeline in February 2016.

“If you have a federal right to put a project in a certain area, a local government can’t come in and say: ‘No, you can’t exercise that right,’” said attorney Carolyn Elefant.

Elefant used to work with FERC. Now she represents clients fighting energy projects, including past opponents of Sabal Trail. She says the federal agency tends to look at the big picture when it comes to permitting energy projects.

“If you have a national interest, you need to be able to build infrastructure, and you need to be able to do it without having states saying: ‘Don’t put it here. Don’t put it here,’” she said.

Jeb Bell has a hard time seeing things that way.

“Last time I looked at a map, Alabama and Florida are connected. If Alabama’s got it, and Florida wants it, leave Georgia out of it,” he said.

His fight still isn’t over.

The Bells still need to settle with Spectra on the value of their land, which should happen at a court date sometime next spring. There are about one dozen other landowners with similar outstanding cases with Spectra.

In the meantime, the Bells are stuck in limbo, in the path of a project they never wanted.

Heavy equipment started rolling into the area this month, and construction starts soon. Spectra wants Sabal Trail up and running by next May.