Section Branding

Header Content

Keeping Stocked With Belugas A Whale Of A Task For Georgia Aquarium

Primary Content

Whale economics: it’s something you’ve got to think about if you’re running a facility like the Georgia Aquarium.

They spent $6.5 million over four years trying to import beluga whales from Russia only to get blocked by the federal government. Now, they’ve said “no” to collecting wild belugas. Instead, they’re trying to keep their whale exhibit afloat through breeding and trading.

But what’s the cost of a beluga? Where do you even get one? How’s the whale market looking these days?

To find answers, head to the Georgia Aquarium, where, if you’re lucky (or can pay a small fee) you can see belugas in action.

Maybe you’ll catch the whales at training time, when trainers clad in wetsuits sit at the top of the 800,000 gallon tank the belugas call home. When they move their arms, the animals respond: popping up out of the water, turning in circles, chattering and shrieking.

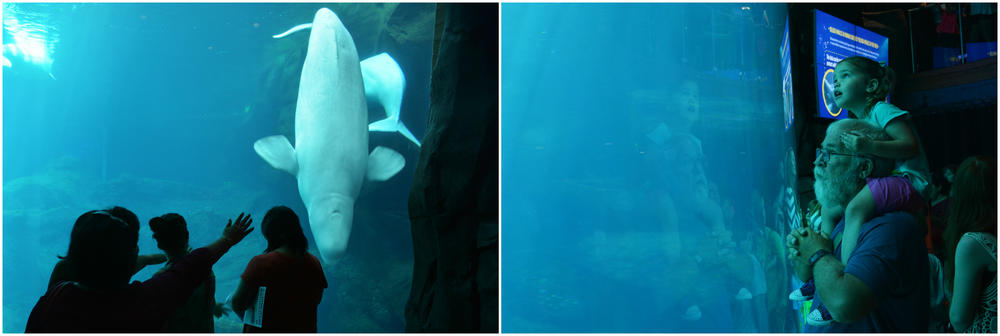

Down front, on the human side of the tank, kids and adults stand, gawking.

Some hold up phones trying to snap a picture. Others hold out their hands to the glass as if they could touch the whales as they slide by. Still others glance at the monitor near the tank rolling through a slideshow of beluga whale factoids.

“They fall in love with them,” said Mike Leven, CEO of the Georgia Aquarium. “It’s hard to fall in love with a fish in the same way you fall in love with a marine mammal.”

Leven’s job is to keep providing that feeling to visitors. That feeling brings 2 million people to the aquarium each year. By one estimate, that feeling has brought almost $2 billion to Georgia’s tourist economy since the aquarium opened in 2005.

But, there’s a tiny (well, maybe more whale-sized) problem.

“It may be that there will be no belugas available to be seen in the United States and that exhibit will go away,” Leven explained.

Captive beluga numbers are shrinking.

The Georgia Aquarium lost one of its whales last year, when a 21-year-old whale named Maris died suddenly. Though Maris gave birth to two calves during her time at the aquarium, both died less than a month after they were born.

According to records from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which tracks captive marine mammal populations, there are only 26 belugas in U.S. aquariums. (There were 27, but one died at the Mystic Aquarium in Connecticut just this week.) It’s hard for the whales to breed effectively in such a shallow gene pool.

The next best option? Buy a whale from a foreign aquarium. But that can be expensive.

“Beluga whales, if you can get them at all, cost in seven figures to get a beluga whale here under the circumstances today,” Leven said. “The market is essentially what you’re willing to pay.”

Even if you have the money, importing a whale isn’t exactly easy, especially because it’s a federally regulated process.

“I like to say: ‘In government, there’s a form for that,’” said Nicole LeBoeuf, Acting Deputy Director of the National Marine Fisheries Service’s Office of Protected Resources.

The agency oversees the Marine Mammal Protection Act, a law that came out of the environmental movement of the early 1970s, which regulates the import of marine mammals like belugas.

“The first thing you need to do is complete and submit an application to import that marine mammal for public display,” LeBoeuf said.

LeBoeuf’s agency reviews that application, shares it with other federal agencies, then opens it up for public comment.

“The big thing that you need to have in your application is you need to make sure [it] meets several Marine Mammal Protection Act criteria to hold marine mammals for public display,” she explained.

You have to be open to the general public, have a license from the USDA, run an educational program, prove your actions won’t hurt the species in the wild, have the right facilities, have the right staff...and LeBoeuf said that’s just the start.

“It’s not something that a mom-and-pop operation is going to be able to get into,” she said.

Even though it's hard to get approval, it's not impossible.

SeaWorld got the greenlight to import three belugas from Canada in 2006. Those whales came from Marineland in Niagara Falls, Ontario. LeBouf said that was the last time belugas were brought into the U.S..

But applications do get denied. That’s what happened with the Georgia Aquarium’s beluga import effort. They tried to get 18 wild belugas from Russia to create a sustainable captive population. Now, the aquarium is strapped for whales.

Not everyone thinks that’s a bad thing.

“The fact that perhaps in 30 to 50 years we won’t have belugas in captivity is my goal, so there’s nothing but positive in that,” said Naomi Rose, marine mammal scientist with the Animal Welfare Institute.

She said it’s time for the Georgia Aquarium to change directions.

“Let’s do what’s right by the animals now, retire them to sanctuaries and move on to Plan B, which is some other exhibit at Georgia Aquarium [or] at any of these facilities that have belugas: replace that exhibit with something else,” Rose said.

She pointed to facilities like the National Aquarium in Baltimore, which recently announced plans to build a sanctuary for its captive dolphins. She said sanctuaries, like aquariums, can still make money.

But, at least for now, the Georgia Aquarium isn’t mulling a sanctuary for its whales. Whales draw visitors, and CEO Mike Leven said they’re not giving up on finding more belugas.

He estimates finding the right whales could cost millions, but said such an investment would only make sense if it helped sustain and grow the country’s captive beluga population.

Failure could mean the beginning of the end of captive belugas in the United States, but, even so, Leven sees a silver lining.

“If we were the only facility in the U.S. that had beluga whales you could raise the price of admission in order to see them, because it’s the only place they could be seen,” Leven said. “For example, if I had a live Tyrannosaurus rex, everybody would come in to see it.”