Section Branding

Header Content

Who Will Pay For Georgia's High-Stakes Test?

Primary Content

Who Will Pay For Georgia's High-Stakes Test?

High-stakes tests are by now a familiar part of our educational system. Their aim is usually clear: making sure students are learning what they need to know to compete with their peers around the country, or even the world. But what isn't so clear is what these tests cost once they are done.

You could see a little of what Georgia's high-stakes test has cost teachers on a Wednesday morning at Heritage Elementary School in Macon.

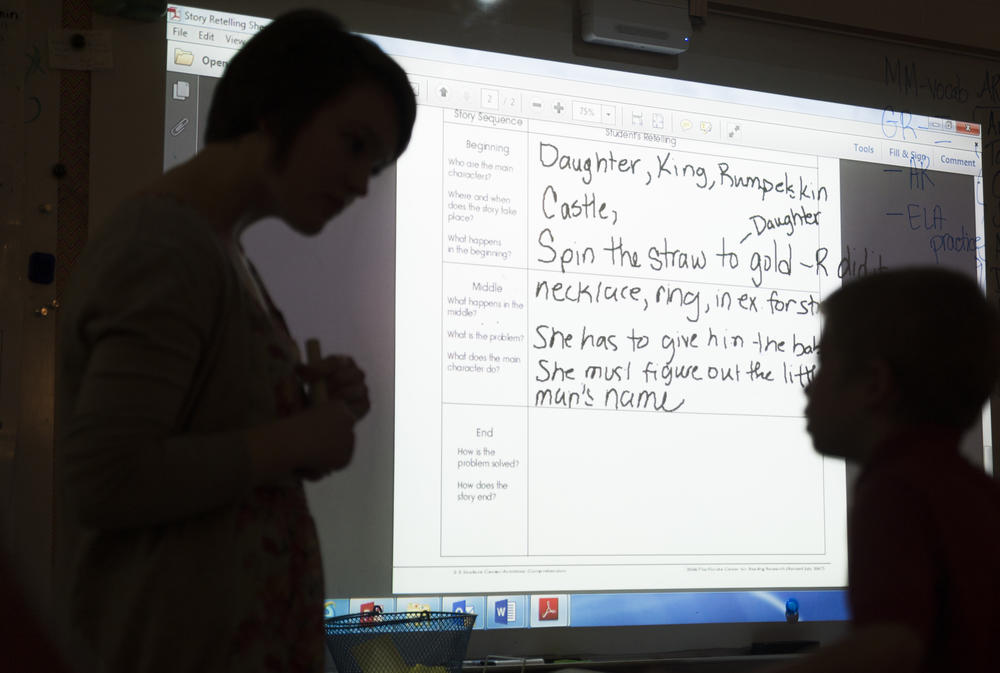

With the lights dimmed so students could read the smart board, teachers Kristie Garnett and Megan Causey led their third grade class through a government lesson recently. At least that was the surface content.

“Laws are passed by what?” Garnett asked in a firm but gentle voice.

“Town Council,” the class intoned.

As they continued like this, students took notes on a short story about a town struggling to cope with an influx of clowns while still maintaining the checks and balances of good governance. Yellow highlighters marked up context clues, key terms, passages to be quoted later in an essay response to the piece. What they are learning is more about the thinking process than about arriving at any correct answer.

So yes, this was a government lesson, but it was really test prep. Garnett said they had been at it for awhile.

“It’s a lot more intense at this time of year, but we start test prep on day one,” she said.

The test that has had Garnett and probably every third, fifth and eighth grade teacher in the state prepping since day one is the Georgia Milestones Test. The open-ended responses, the complete absence of multiple-choice questions, it is kind of daunting at first look. In this, its second year, the test is tied directly to promotion from those grades. For a third grader to move on, they have to read at grade level. Fifth and eighth grades must hit grade level in reading and math.

MAP: Where Third-Graders Could Be Held Back Most

percent_of_georgia_3rd_graders_below_grade_level_in_2015 1

Map created by GPB Macon in CartoDB

The counties that could have held back the greatest proportion of their third-grade cohorts are among Georgia's poorest, in the large agricultural belt. Map data courtesy of Neighborhood Nexus/Reading data courtesy of Georgia Department of Education

Had the promotion policy been in place in 2015, it would have created some interesting demographic problems. The policy could have added almost one and a half extra third grade classrooms of 25 students a piece for every elementary school in the state, affecting some 41,382 third grade students. In Gwinnett County, the pass/fail rule would have created 140 extra third grade classrooms. That's even though the county outperformed the state average. In Heritage Elementary's Bibb County School District, 50 extra classrooms would have been needed.

Tanzy Kilcrease, Assistant Superintendent for Teaching and Learning in Bibb County, said her district has been planning since February for what comes after the test so that class sizes don’t balloon.

“We're providing a free summer opportunity for our students where they will receive additional assistance and further instruction in the areas of reading and math,” she said.

MAP: Where Third-Grade Classes Could Balloon The Most

2015 Georgia 3rd Grade Reading Assessment

Map created by GPB Macon in CartoDB

Metro Atlanta counties would have experienced the greatest growth in third-grade class size. Despite outperforming the state average, Gwinnett County would have required 140 extra third-grade classes. Map data courtesy of Neighborhood Nexus/Reading data courtesy of Georgia Department of Education

Of course it isn’t actually free. It will take teachers, administrators, even bus drivers to staff two separate school sites for 15 days in June, five hours a day. And every school district in the state is left to come up with some version of this remedial effort. So how much will that cost the Bibb County School District?

“I cannot put a price tag on that just yet,” Kilcrease said. “Not even a ballpark figure.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kgsTbs979XM&feature=youtu.be

As it turns out, the summer school efforts might not even matter.

While the state strictly monitors the Georgia Milestones testing and grading, local school districts are left all to themselves to decide whether or not to promote a student. Districts are not bound to uphold the State’s pass/fail policy, the same policy that has had teachers teaching to the test all year. For instance, in Bibb County, students and parents can also petition their principal for a promotion. State Schools Superintendent Richard Woods sees that as a chance for school districts to set their own path.

“And so if they set the pathway we're here to stand side by side with them and make sure that they succeed,” Woods said. “And offer the resources of the State to help them along the way.”

Tanzy Kilcrease said students will not be rubber-stamped into the next grade. Superintendent Woods said he trusts that will be the case statewide. As for the resources of the State, Kilcrease will get no money from the State Department of Education for summer school. No one will. So Kilcrease is getting creative.

“For example in our textbook budget there are some funds that are available,” she said.

So if there’s no extra cash, what instructional advice does Superintendent Woods have for what comes after the Georgia Milestones Test?

Leah Austin, Vice President for Programs for the Southern Education Foundation, says that’s not good enough.

“I still think outside the box is an interesting term when we keep sort of defining and redefining the box,” she said in reference to the only two-year-old test.

Austin is in the business of turning educational research into system wide instructional prescriptions. One area of focus is expanding K-12 literacy. She says you can’t ask schools to adapt to a new high-stakes test without help and call it a return to local control. What about the bare-bones logistics of the following school year? Assuming the pass/fail policy stands, that is.

“If you're going to have more students being retained, then you're going to have potentially larger class sizes,” she said.

Worst case, Georgia would have added almost three eighth-grade classes for every middle school in 2015. Do that for a number of years, and Tanzy Kilcrease in Bibb County says the costs could rack up.

“It would be a financial impact. Yes it would,” she said.

Superintendent Woods says the money talk misses the larger point: there’s a ton of great data here. But even he asks: why wait to do this at the end of the year?

“I’ve often referred to this as an autopsy type report,” he said.

He says a start of the year test would be like a physical exam teachers could teach from rather than teach to.

Leah Austin says even that would remain tainted by the threat of the pass/fail policy.

“I think the punitive outcomes are just unhelpful,” she said. “You know it sort of lessens this idea that there's data and expertise that you have beyond an assessment that tell you so much about your students.”

Teacher Kristie Garnett is already thinking ahead to the conversation with her son’s principal. As it turns out, he’s a special needs student in the third-grade.

“Do I think it's in every child's best interest to repeat third-grade? No,” she said. “Now do I think it's in my child's best interest? Probably not.”

For some kids, though, Kristie Garnett says retention is the best thing to do.

Secondary Content

Bottom Content