Section Branding

Header Content

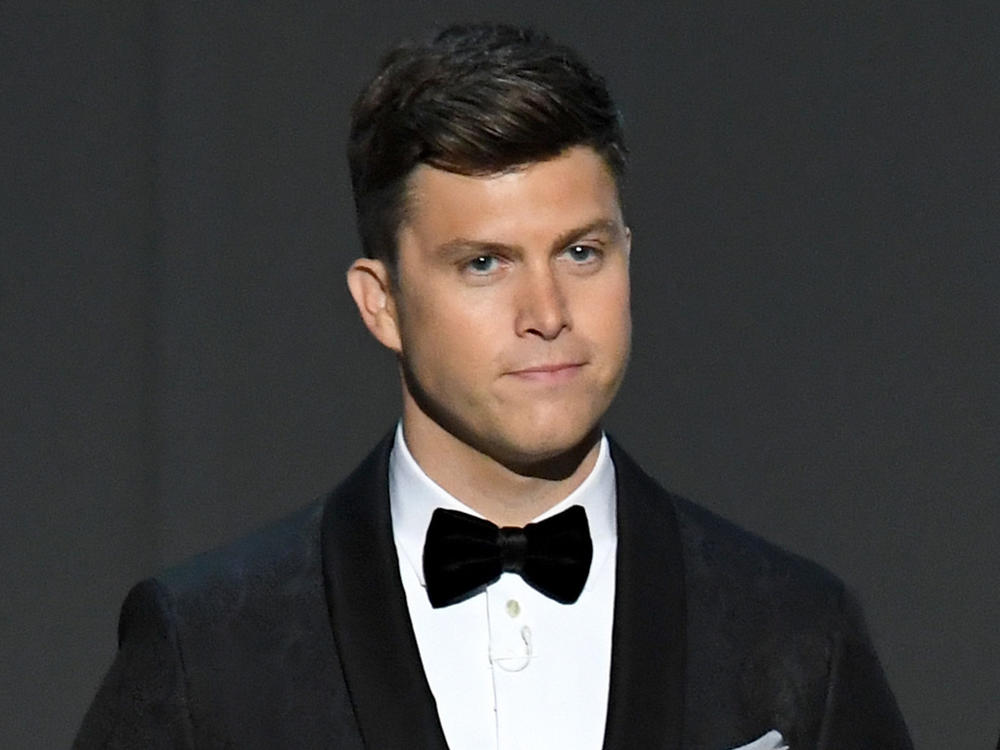

Colin Jost Of 'SNL' Knows You're Laughing At His 'Very Punchable Face'

Primary Content

Saturday Night Live's Colin Jost knows there's something about his clean-cut image that rubs some people the wrong way. When he joined SNL as a writer in 2005, he worked off-camera — and didn't have to think about his looks.

"When you're not on camera or on television, you don't really consider what you look like," he says. But all that changed when he began working on-air in 2014 as the co-anchor of the show's "Weekend Update."

"Some people look at me and have sort of a visceral, angry reaction [to me]," he says. "You see it in our audience. When I get hurt or hit on camera — like when [castmate] Cecily [Strong] throws drinks in my face or throws up red wine on me — the audience really loves it."

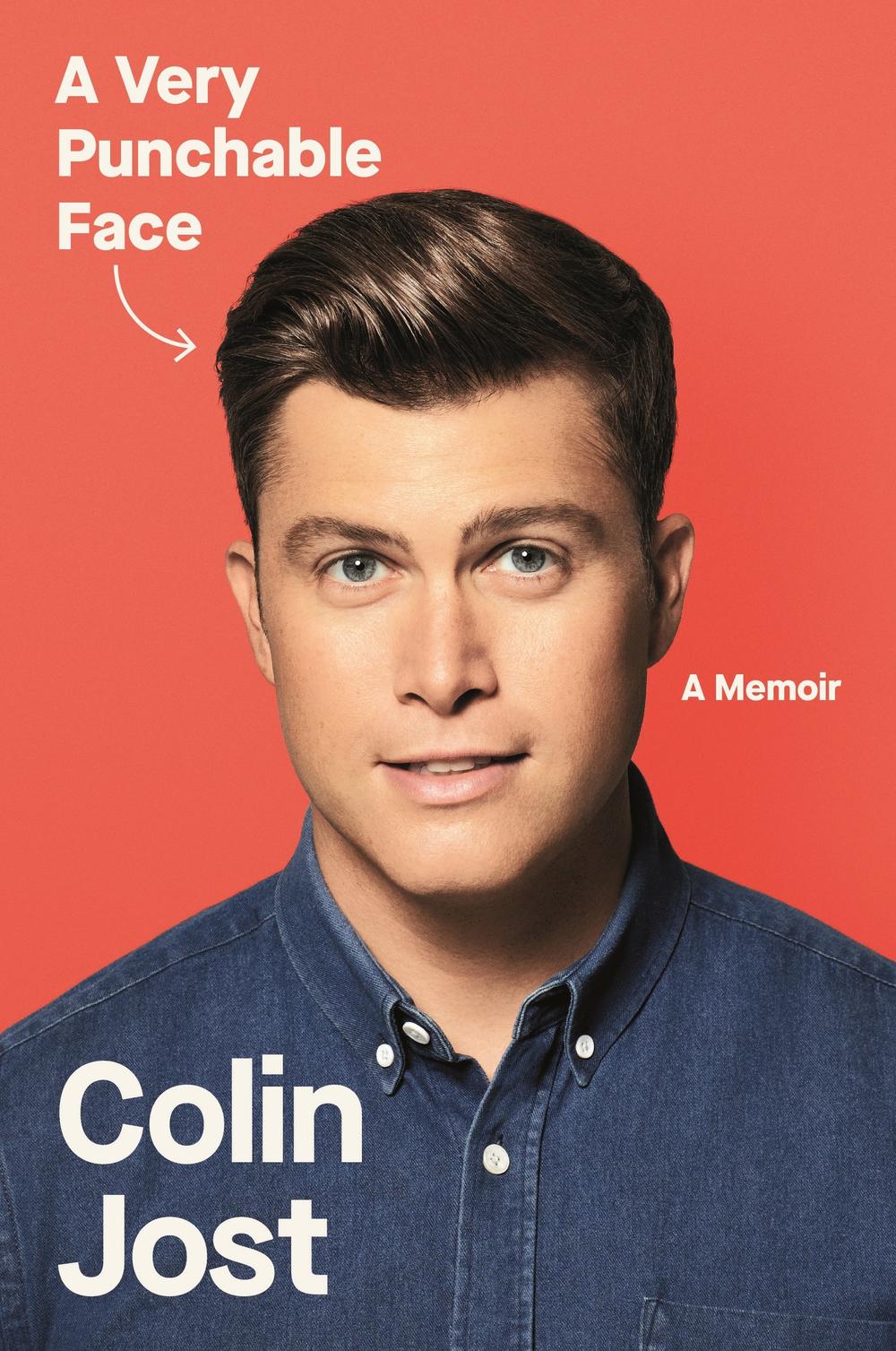

Jost's new memoir, A Very Punchable Face, describes his experiences growing up in a middle-class household on Staten Island.

"Part of writing this book was being excited to talk about parts of my life and weird episodes in my life that I thought that would be entertaining for people," he says. Or, he adds, for people to "just get another chance to laugh at me."

Jost has been a co-head writer at SNL, following in the footsteps of Tina Fey and Seth Meyers. While he's not ready to leave the show just yet — he does think about it.

"It's a world that I love so much," he says. "You just don't know how often you get to work at a place like that, and the odds are zero other times in my life will I get to work at a place like that. So it's a scary but a necessary decision to face at some point."

Interview Highlights

On gravitating toward writing because it was difficult for him to articulate what was in his head

I think the feeling is a lot of ideas and words are jumbled around, and I want to get it all out, and it's like I can't. It's almost like you're trying to funnel a lot of words or ideas, and they're not getting through that hole at the bottom of the funnel. They're backing up, and you're trying to get them through either in an orderly fashion or all at once. But it's not happening. There's almost like a slight delay sometimes when I'm talking because I'm trying to kind of get things together in my head before they come out.

On how he didn't speak until he was 4 years old

I remember a feeling of frustration at that period of my life. It's always hard when you're looking back because what your memories are at that age are also informed by what your parents tell you about that time. I definitely remember having angry outbursts, like physical outbursts, because I felt frustrated that I wasn't communicating with words — that I remember. I remember my speech therapist. I remember meeting with her, and I remember a profound sense of relief that this other gate was open or something ... [being] able to finally talk. It was just a relief, I would say, more than anything.

On his mom working as chief medical officer in New York for more than two decades

She was in the fire department for 40 years. ... She has lung issues from [the Sept. 11 attacks]. Obviously it's scarier in this time we're with COVID and stuff, but she's a healthy person who tries to be conscious of that and make decisions that help her health. ... One of the first things she did [after Sept. 11] was to set up a triage center that was like in an old Duane Reade ... and then set up another center later at Pace University. I think that she was expecting, everyone was expecting, waves of people who were injured, and there was a little bit of an initial wave. But very quickly, people realized that it was not an injury situation, it was how many people had died. And so it became more of a search and a recovery than it was like treating individual injuries. ...

I was very worried about her, and I didn't talk to her for a long time. ... [Growing up] my mom was always on call, like she'd be on call certain days, like all night. So I was used to late at night, my mom coming and waking me up and saying, "Hey, I got to go to work." And I'm like, "Oh, why now?" And she's like, "Well, there's a fire." ... But when someone's just survived something, you want them to be in a safe place and not put themselves in more danger. That was scary for a while.

On having many firefighters in his family

There's very few people in my family, [on] my mom's side, who are not firefighters. My grandfather was a firefighter. My great-grandfather, my uncle is a fire dispatcher. I think I have three cousins who live on our street [on Staten Island] who are firefighters. ...

They loved it as a community, and they also loved it as a steady, city job. They really appreciated that you could earn a living as a firefighter, build a family as a firefighter. And they love the people they worked with. So I just grew up thinking of it as this great community in this great world. When I didn't get jobs as a writer or my brother was struggling to get jobs as a writer, [my mom] would always tell us, "You can take the fire department test. It's coming up!" I think she's still told my brother that about two months ago, even though he's been very gainfully employed for 10 years.

On his SNL 'Weekend Update' co-anchor Michael Che writing jokes for Jost to say about race that sometimes he doesn't see until he says them live on TV

The hard thing is you kind of need an audience to guide you about what's too far. Some of the jokes that we do, I have not seen the joke until air, so I'm pretty much putting my life in Michael Che's hands a lot of times and hoping that he knows what that line is. But it's a very terrifying moment ... when Michael Che makes me read a joke that I have not seen before on live TV, which occasionally happens; I'll hear things backstage in passing like one of the other writers saying, "You can't make him say that!" But I don't know what it was. And I don't think anyone particularly knows what's too far or not too far. People have different opinions about that. I think you really have to trust ultimately that if you're coming at something from a good-hearted place and you're well-meaning and what you're doing, I think you have to go for it and then hope that the people are open-minded.

Sam Briger and Seth Kelley produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Beth Novey adapted it for the Web.

Copyright 2020 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.

Bottom Content