Section Branding

Header Content

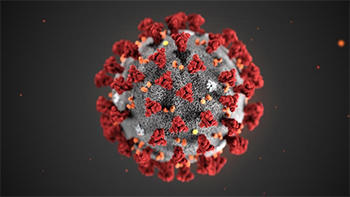

How The Coronavirus Pandemic Magnifies Health Inequities - And Why Mitigation Matters

Primary Content

The coronavirus pandemic has led to travel restrictions, canceled events, school closures, consumer panic, and mayhem in stock markets across the world.

The spiraling fears and slow access to tests for the virus in the U.S. have exposed weak points in government and health care systems, as well as the social fabric upon which we rely — especially for the most vulnerable.

"On Second Thought" host Virginia Prescott speaks with Dr. Keren Landman and Dr. Carlos del Rio.

Dr. Keren Landman, a doctor, epidemiologist and journalist, joined On Second Thought to discuss how existing inequities play into the risks — and outcomes — of a global pandemic. She pointed out that people from lower socioeconomic backgrounds may not be able to work from home, are less likely to have sick leave or paid time off, and are more likely to live paycheck-to-paycheck. And for them, self-quarantining is not a realistic option, which could lead to even more spread of the virus.

"People who are lower income generally live with more people in a household," she explained. "They have fewer bathrooms per household. They share more space, so disease is going to spread more easily in that kind of environment — and then go back into the workplace with all the other people who live in that household. So it's a recipe for more spread among people with lower incomes and less access to sick leave."

Dr. Carlos del Rio, chair of the Department of Global Health and professor of epidemiology at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University, where he's also professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases, also joined the conversation. He pointed to how epidemics reveal weak points in public policy.

"We were saving money by not having access to healthcare, by not having social programs," he said. "And now we're going to pay, right? So being cheap, it's going to cost us a lot, and we need to remember that. Going forward, I would think that, as a nation, we start thinking better about preparing for these kinds of events."

For all GPB coverage of coronavirus, visit gpb.org/coronavirus. For the latest health and safety recommendations regarding the disease and its spread, please visit the CDC.

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS

On the panic resulting from the spread of coronavirus

Dr. del Rio: You know, we're all a little anxious. We're a little concerned because we really don't know where this is going. I tell people this is a little bit like, you know, there's a hurricane coming and we don't know [if] it's gonna be a Category 4 or a tropical storm. What we need to think about is, as a state, as a federal government, as a local government — we need to prepare for the worst and hope for the best.

On the steps toward mitigation of the spread of coronavirus

Dr. del Rio: Because I do think there's been a lot of community transmission, as we test more, people are going to find more cases, and that doesn't mean that these cases are happening right now. We may be picking cases that happened several weeks ago. And I tell people, “Testing right now is going to be like looking at the light coming from the sun, or a star. It didn't come right now, you know, it traveled there.” So what we need to do right now is three things — critical things that need to happen — or four. Number one, identify infected individuals. Isolate infected individuals. Aggressive contact tracing, so we can then diagnose the contacts and isolate them as well, or do quarantine of those who have been exposed. And the final thing we have to do is prepare our healthcare system. And if we do those things, then what we will achieve is what we call “mitigation.” We will still have cases, but we're going to spread them out over time and, therefore, there's not going to be panic. And that is critical right now. We need to move into this mitigation phase.

On the impact to lower socioeconomic communities and individuals who may not be able to afford to take time off from work

Dr. Landman: That means that people are not going to stay home; they're going to go to work. And that means that they will become infected at a higher rate than people who are able to stay home and quarantine or isolate themselves. And they're also going to bring those infections back home to their families. People who are lower income generally live with more people in a household. They have fewer bathrooms per household. They share more space, so disease is going to spread more easily in that kind of environment — and then go back into the workplace with all the other people who live in that household. So it's a recipe for more spread among people with lower incomes and less access to sick leave.

Virginia Prescott: How about in Georgia, particularly, or Atlanta?

Dr. Landman: So in Atlanta, 18.5% of metro Atlantans don't have health insurance. 22.4% of Atlantans live in poverty. So that means a couple of things. Number one, these people are not going to be able to stock up and prepare to stay home as easily as somebody who has just a higher amount of money in the bank, who has a better financial cushion, and can prepare. Number two, those people are not going to go get health care as quickly if they do get sick — and may not get the right advice that they need to stay home if they are ill. People without resources often really want to work. They want to go to work. They need to go to work because they need that paycheck, and they won't get paid if they don't. So they're not, they're totally disincentivized to do the things that they would need to do for these social distancing measures to work.

On how epidemics like this reveal the need for social safety nets and broad access to healthcare

Dr. del Rio: This is costing billions of dollars. And I love the quote from Dolly Parton that says, “You have no idea how expensive it is to look this cheap.” And we were saving money by not having access to healthcare, by not having social programs. And now we're going to pay, right? So being cheap, it's going to cost us a lot, and we need to remember that. Going forward, I would think that as a nation, we start thinking better about preparing for these kinds of events. And not only as a nation, but I mean, we need to think globally. How do we prevent global epidemics from happening? Because investing in global health security, investing in social safety nets — and a variety of different things — actually is going to help us prevent epidemics. So I think it's a good time to have that discussion.

On less obvious ripple effects of caution and quarantines in response to coronavirus

Dr. Landman: So I volunteer at a homeless shelter; I provide clinical care, and it's a monthly clinic that I attend, but it's an every-week clinic that they actually run. The clinic is open seasonally during the wintertime and it's staffed, actually, the entire shelter is staffed by volunteers, many of whom are older — above 60. And they're having to close down early this year because volunteers are at higher risk for contracting and suffering severe illness from the disease. And the homeless shelter is a perfect environment, unfortunately, for a disease like this to spread. So here's a sort of unusual situation in which you have a vulnerable population suffering because a sort of more privileged population is at risk for a worse outcome from this pandemic.

On what other countries are doing in response to the coronavirus pandemic

Dr. Landman: Japan has done some interesting things. They implemented a lot of school closures, and they offered subsidies to help companies offset the cost of parents taking time off because their children had to be out of school. And they're also offering some financial help to small businesses and healthcare providers who are having a decrease in their income, or increasing the amount of work and the amount of workers that they're having to hire. France has promised 14 days of paid sick leave to parents of kids who have to self-isolate, if they have no other choice but to watch their kids. These are taken, by the way, I should credit a New York Times article on this subject. Other countries are thinking about a social safety net and about augmenting an already existing social safety net in ways that that we could learn a lot from.

Get in touch with us.

Twitter: @OSTTalk

Facebook: OnSecondThought

Email: OnSecondThought@gpb.org

Phone: 404-500-9457