Section Branding

Header Content

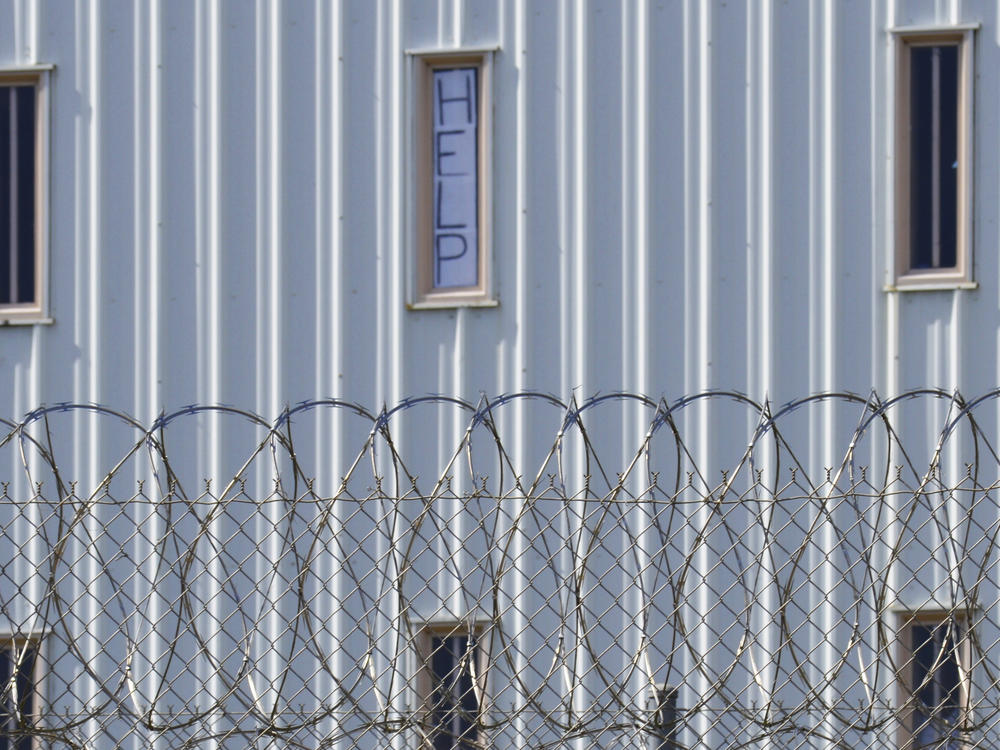

DOJ: Alabama Prisons For Men Are Unconstitutional Because Staff Abuse Inmates

Primary Content

The federal government has put the state of Alabama on notice again for unconstitutional prison conditions. The U.S. Department of Justice, along with U.S Attorneys in Alabama, released a report Thursday that details widespread excessive use of force against male prisoners.

"Our investigation found reasonable cause to believe that there is a pattern or practice of using excessive force against prisoners in Alabama's prisons for men," said Assistant Attorney General Eric Dreiband for the Civil Rights Division.

The DOJ investigation found that Alabama corrections officers frequently use excessive, and at times, deadly force in violation of inmates' constitutional rights in 12 out of 13 prisons reviewed. It concludes the problem gives rise to "systemic unconstitutional conditions" and that "such violations are pursuant to a pattern or practice of resistance to the full enjoyment of rights secured by the Eighth Amendment."

The report says the use of batons, chemical spray and physical altercations such as kicking and beating often resulted in serious injuries and at least two deaths last year. In one fatal incident in October 2019, "the level of force used caused the prisoner to sustain multiple fractures to his skull, including near his nose, both eye sockets, left ear, left cheekbone, and the base of his skull, many of which caused extensive bleeding in multiple parts of his brain," according to the DOJ findings.

Investigators say severe overcrowding and under-staffing contribute to a pattern of excessive use of force by increasing tensions and escalating episodes of violence in a climate with inadequate supervision, and little to no accountability. "Ultimately, Alabama does not properly prevent and address unconstitutional uses of force in its prisons, fostering a culture where unlawful uses of force are common," the report says.

This is the latest from an investigation that dates to 2016. The DOJ has already found that Alabama was "deliberately indifferent" to pervasive prisoner-on-prisoner attacks and sexual abuse, and failed to maintain facilities that are "sanitary, safe, or secure."

Republican Governor Kay Ivey calls the report an "expected follow-up" and says her administration will be "carefully reviewing these serious allegations" and working with the federal government to resolve the issues.

"I am as committed as ever to improving prison safety through necessary infrastructure investment, increased correctional staffing, comprehensive mental-health care services, and effective rehabilitation programs," Ivey says. "We all desire an effective, Alabama solution to this Alabama problem."

It's been a familiar refrain as the state tries to remedy chronic unconstitutional conditions that have plagued Alabama prisons for decades. But reform efforts have been piecemeal at best. The governor is moving ahead without legislative support on a billion dollar plan to recruit private developers to build three new prisons which the state would then lease.

"This unconstitutional behavior will not be solved by building newer, larger prisons," says Ebony Howard, senior supervising attorney for the Southern Poverty Law Center which sued the state over inhumane conditions.

"The violent conditions and circumstances outlined in the DOJ's latest report are at the hands of prison personnel and demonstrate failures of the Alabama Department of Corrections' leadership to ensure people in their custody are safe," Howard says.

In addition to the DOJ pressure, a federal judge has ordered the state to improve the way it treats mentally ill prisoners. U.S. District Judge Myron Thompson ruled in 2017 that Alabama puts prisoners' lives at risk with "horrendously inadequate" care and a lack of services for inmates with psychiatric problems.

"While we recognized the challenges of correcting systemic constitutional deficiencies in Alabama prisons that have existed for decades, now is the time for significant reform," says Richard Moore, the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Alabama.

The DOJ is calling for immediate measures to remedy the excessive use of force by corrections officers including implementing a grievance procedure, keeping track of reported abuse through a database that can identify patterns of force, and increased use of video cameras to document what's going on. It also says the state should modify its regulations to explicitly state that "strikes or contact to the head constitute a form of lethal force" that should only be used to protect life or serious bodily injury, and to require timely medical assessment after a use of force.

The notification letter sent Thursday says Alabama officials have 49 days to address the Justice Department's concerns or the U.S. Attorney General may sue.

While Gov. Ivey has shown a willingness to work with the federal government, Republican State Attorney General Steve Marshall is adamantly against Alabama entering into a legal agreement with the federal government over prison conditions.

"In short, a consent decree is unacceptable and nonnegotiable," says Marshall. "The State of Alabama shall retain her sovereignty."

Marshall says the state was "ambushed" by Thursday's DOJ report and says the state has never denied "the challenges" facing the Alabama Department of Corrections. He says he will not submit the state to judicial oversight of prisons.

"Alabama will not be bullied into a perpetual consent decree to govern our prison system, nor will we be pressured to reach such an agreement with federal bureaucrats, conspicuously, fifty-three days before a presidential election," says Marshall.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.