Section Branding

Header Content

Protests May Prompt Dialogue On Racism, But 'It's Going To Be Uncomfortable'

Primary Content

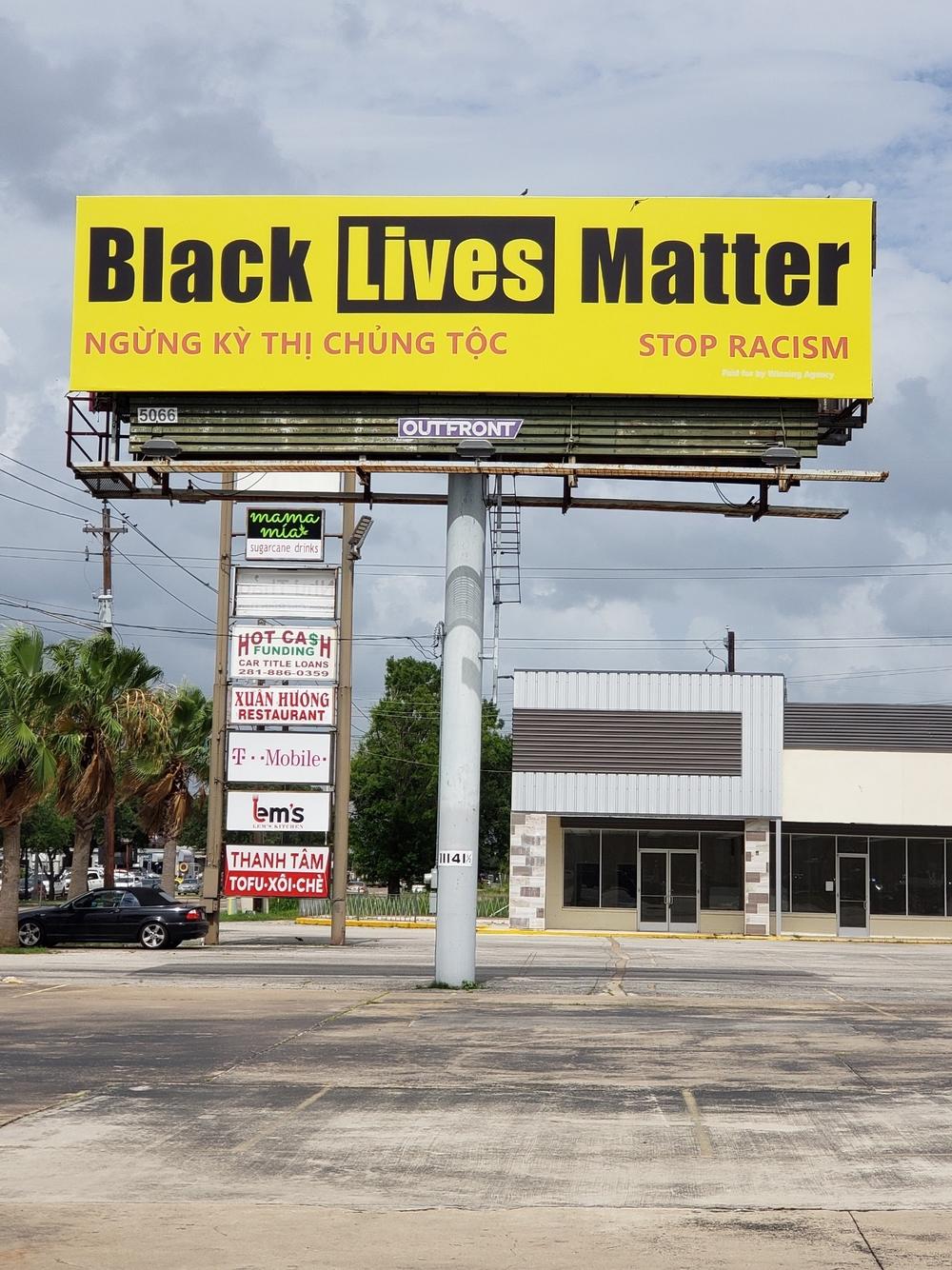

When Le Hoang Nguyen put up a bright yellow billboard in support of the Black Lives Matter movement in Houston, the pushback from his community, "was immediate, it was vicious, my Facebook wall filled up with just hate speech."

Nguyen's original idea for the billboard was to thank essential workers for their work during the pandemic, but when George Floyd was killed, he felt strongly about supporting BLM.

The insurance business owner knew that some people wouldn't like the message, but he thought people would respectfully agree to disagree.

"I was totally blindsided. It was unnerving," he said. "They threatened with physically destroying our office, they called for a boycott of our business, people posted photos of my family online. No one wanted to have a conversation, they were just making threats and demands."

In spite of the massive protests across the country in support of racial justice and the Black Lives Matter movement, racial divisiveness continues to manifest itself around the nation, though sometimes it can be more subtle.

Nguyen appeared on a local Vietnamese television show to explain himself to his community and he says that helped. Eventually, people on social media started defending him, and this "helped quell the haters."

Floyd was killed on May 25, which was also Nguyen's 50th birthday.

"I broke down in tears when I heard him cry out for his mama before he drew his last breath," Nguyen said, adding that it could have been him or any of his three children in that video, "underneath that knee."

Soon after Floyd's death Nguyen came across an ad published in The New York Times in the late '70s by a group of Black leaders urging President Jimmy Carter and Congress to allow refugees from Southeast Asia into the country.

"That was me," the Vietnamese-born U.S. citizen said. "I was an 8-year-old boy languishing in a camp, and halfway around the world a group of Black civil rights leaders spoke up for me."

"It's going to be uncomfortable"

It's not easy to talk about race, even in communities seen as more liberal. In Brooklyn, N.Y., a man protested a BLM sign, repeatedly asking the barista at Burly Coffee to remove it. The New York Times recently reported that in Catskill, N.Y., town leaders banned a BLM painting on main street. Many communities have created groups to engage in conversation. In New York there's Hastings-on-Hudson, a village with its Hastings Against Racial Injustice, and Carmel, Ind.'s Group For Carmel Against Racial Injustice.

"It's going to be uncomfortable and you're going to have legitimate fear," if you choose to engage in racial equity dialogue, said Kwame Christian, director of the American Negotiation Institute in Ohio.

"When we are exposed to ideas that are different from our own, we interpret it as a threat," Christian said.

For many people it may not be worth the risk, but Christian says conflict is an opportunity. He urges people to reflect, and to be intentional and informed because it helps people to understand the impact of their action or inaction. And he says people often lack compassionate curiosity or the ability to acknowledge someone else's emotions.

"I needed to say something"

Anya Randall Nebel is a 54-year old Black woman, her husband Joe is white. They've lived in Chevy Chase, Md., a wealthy enclave outside of Washington, D.C., since 2006. Watching the video of Floyd being killed forced her to examine her own experiences in her community.

"I felt that after 18 years of sitting silent, I needed to say something," Randall Nebel said.

Last month, the software expert wrote a message to her community's e-mail listserv.

"Black in Chevy Chase," Randall Nebel wrote in the subject line. "It has taken me quite a while to share with you my adventures in our fair town."

She wrote about attending the town's annual Fourth of July picnic. "We were met with stares, rudeness, just the feeling of uneasiness," and about the times at the playground with her daughter when people would ask if she's a nanny or if she lives here. She said she's felt unwelcome. People often made assumptions about her and her politics, especially during President Barack Obama's tenure.

Randall Nebel said she wrote her email to start a real give and take conversation on race with her neighbors, but that didn't happen. Several responded to Randall Nebel's email but the moderators made the decision to not publish them essentially halting the conversation.

Randall Nebel describes her neighborhood as largely liberal, "but liberal where it's [a] 'not in my backyard' and 'it's not my problem' type thing."

"This conversation, this dialogue has to happen [in the open] in order for us to get past or move on," she said. "I was waiting for it."

Randall Nebel said she values the opportunities her daughter has had living in the tree-lined suburban town, but as one of the few black residents she has also felt isolated.

"Don't do it because it's fashionable"

According to the 2010 Census, 94.3% of residents in the Town of Chevy Chase are white. The town is a subdivision of Chevy Chase, an expansive residential area founded by a segregationist, Sen. Francis G. Newlands in the late 1800s. Blacks and Jews were not welcome. Part of Newland's legacy is a prominent sandstone fountain named for the senator. Last month a neighborhood commission voted to change the name.

The Black Lives Matter movement is challenging convention, from the symbolism of the 82-year old fountain to BLM lawn signs.

Soon after Floyd was killed, Randall Nebel's neighbors began raising the question of how to lend their voices to the social justice movement. Several people mentioned Black Lives Matter yard signs. Soon they began popping up in her neighborhood, Randall Nebel said.

"I got tired of everybody going, 'Hey, let's get these Black Lives Matter signs and put them in our yard,'" she said. "I'm like, don't do it because it's fashionable."

She says it's telling that many in her community felt safe putting up a BLM yard sign, but open dialogue made some uncomfortable.

Sharing her experiences felt cathartic for Randall Nebel.

"It was a relief," she said. "It was a weight off of my shoulders, because I had been holding it in for a long time."

After Randall Nebel's listserv email, the town formed a committee on racial and social justice to foster conversation. She sees that as progress, but says white people need to be willing to do the hard work and not expect Black people to explain racism, she said, "because we are tired of it."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.