Caption

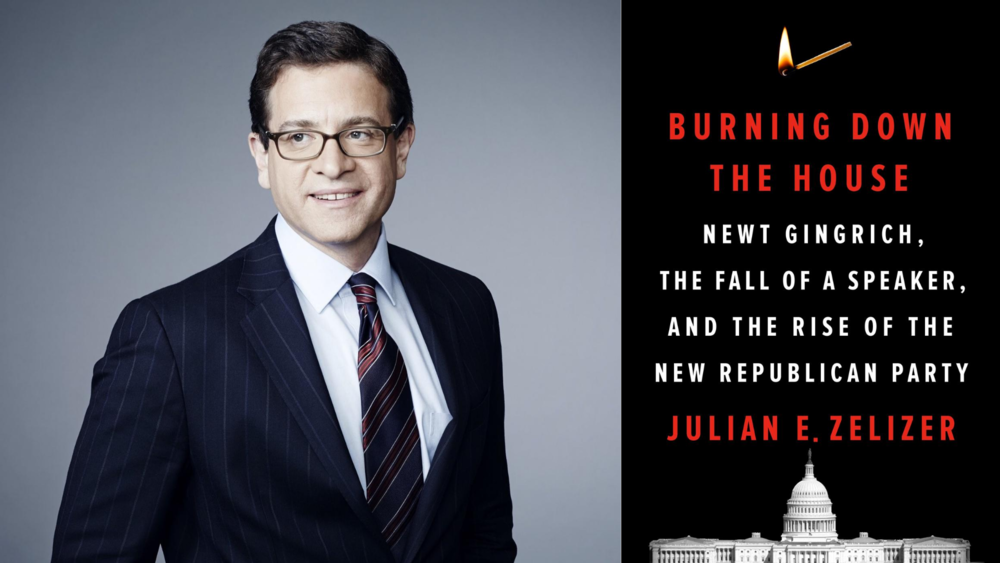

Julian Zelizer's latest book, "Burning Down The House," offers one potential theory for why the American political environment has become so toxic: former Georgia congressman Newt Gingrich.

Credit: Courtesy of Julian Zelizer; Penguin Randomhouse