Section Branding

Header Content

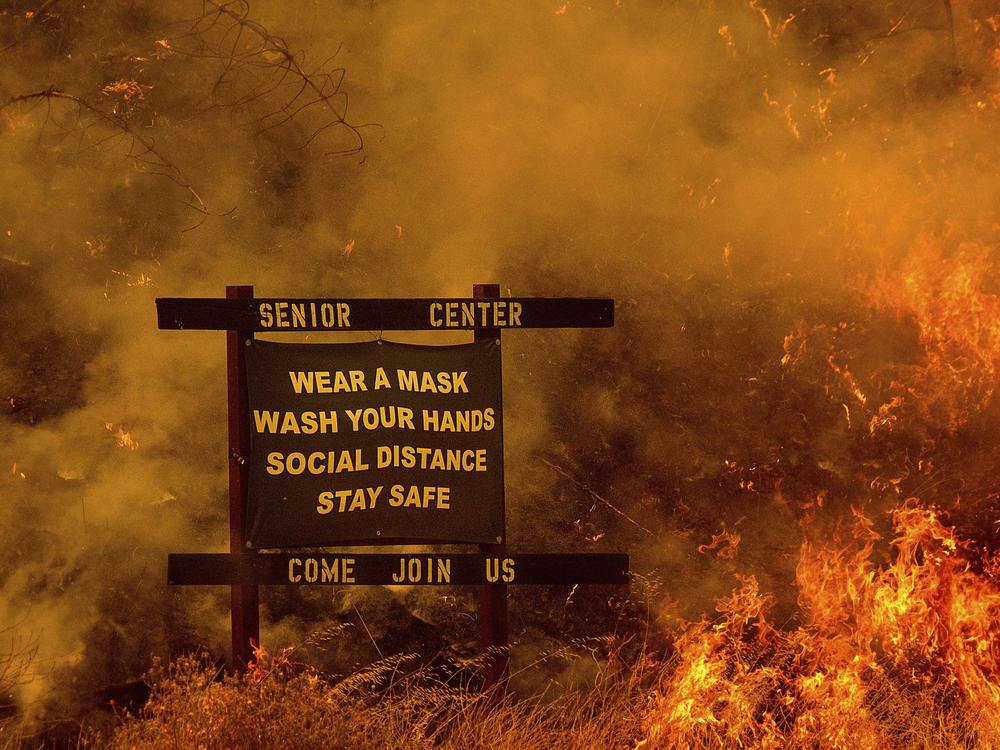

Wildfires Rage In California As Fire Crews And Evacuees Grapple With COVID-19 Risks

Primary Content

Updated 1:05 p.m. ET

Lightning strikes, extreme weather conditions, dangerous levels of smoke and ash, and a deadly pandemic are pushing firefighters and the communities they're trying to save into uncharted territory.

Roughly 11,000 lightning strikes over a few days spawned nearly 370 individual fires that have killed at least five people, and led tens of thousands to evacuate. Nearly 600,000 acres are burning in the eight largest fire complexes as of Friday morning, and California's firefighters have had to work in steep and difficult-to-access terrain under record-breaking temperatures.

But COVID-19 adds a new dimension of risk to the job, both on and off the front lines, and poses new threats to those seeking refuge in temporary shelter.

Christine McMorrow, a spokeswoman for Cal Fire, tells NPR there are several new protocols in place to prevent firefighters from getting sick.

She notes that fire crews are already armed with significant personal protective equipment while they're battling active fires. That includes gloves, face and neck shrouds, and protective eyewear.

When they're at base camps, firefighting personnel are required to wear face masks and maintain physical distancing, McMorrow says.

"We are also spreading out," she adds. "Instead of being in a concentrated smaller space, we're taking up more space."

The crews, which number in the hundreds, would ordinarily set up base camp on small grounds near the fires. But because of COVID-19, McMorrow says they are housed in hotels or setting up on vacant fairgrounds outfitted with "more hand-washing stations."

Meals are also being staggered to keep crews separated, and everyone gets regular temperature checks, she says.

The virus has also created new challenges for those battling the flames.

"They can't put as many firefighters next to each other on the fire line," Bill Stewart, a UC Berkeley wildfire expert, told the Sacramento Bee. "The pickup trucks (transporting crews) are historically full of people. Now they're limited to one or two."

The effects of early release prison programs that have been expedited by COVID-19 outbreaks are also evident at the dozens of wildfire sites.

California employs nearly 200 inmate crews to battle brush fires. But as of Thursday, McMorrow says they were falling far short of that.

Of 192 possible crews only 113 are staffed, she says, and as of Thursday only 102 are deployed.

"That totals 1,306 incarcerated firefighters deployed to 19 fires," she says.

As NPR has reported, "Many inmate firefighters were sent home from prison after the state granted early release to thousands of prisoners to depopulate crowded facilities and slow the spread of the coronavirus."

As McMorrow explains, one of the reasons is that the inmates who are eligible to volunteer for firefighting training "are low-security, low-risk population and those are the folks that are being released."

On Wednesday, Gov. Gavin Newsom announced that an additional 830 seasonal fighters have been hired in the past few weeks to offset the losses. More help is expected to arrive from Texas in the coming days.

Meanwhile, as thousands of evacuees flee their homes they must be sheltered in coronavirus-safe environments.

On Wednesday night, the Red Cross provided lodging in community centers, gymnasiums and hotel rooms for more than 600 people, Greta Gustafson told NPR.

Gustafson said officials ensure there is adequate space between cots and they use "enhanced cleaning and disinfecting practices." Additionally, every person going into a shelter undergoes a health screening and is given face masks.

Despite those precautions, some are unwilling to risk exposure to COVID-19.

Some people refused to leave their homes when officers went door to door Wednesday night, Cal Fire Chief Mark Brunton told The Associated Press.

Among them was Kevin Stover, a camera operator and rigger turned DoorDash and Lyft driver.

Stover was contemplating ignoring the Thursday morning mandatory evacuation issued for Felton, a small town outside the beach city of Santa Cruz.

"I don't want to leave," he told the AP.

The governor addressed the wildfires Thursday night during the Democratic National Convention.

Newsom was scheduled to deliver a lighthearted address leading up to presidential candidate Joe Biden's speech but swapped that out for a video recorded in a forest near Watsonville in Santa Cruz County.

He called the fires in his state clear evidence of climate change.

"If you are in denial about climate change, come to California," Newsom said.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.