Section Branding

Header Content

As Disasters Roil Earth, A New Sun Cycle Promises Calmer Weather — In Space

Primary Content

Giant flares and eruptions from the sun can cause space weather, and stormy space weather can interfere with everything from satellites to the electrical grid to airplane communications. Now, though, there's good news for people who monitor the phenomenon — the sun has passed from one of its 11-year activity cycles into another, and scientists predict that the new cycle should be just about as calm as the last.

That doesn't mean, however, zero risk of extreme weather events. Even during the last, relatively weak solar cycle, drama on the sun triggered occasional weirdness on Earth like radio blackouts, disruptions in air traffic control, power outages — and even beautiful aurorae seen as far south as Alabama.

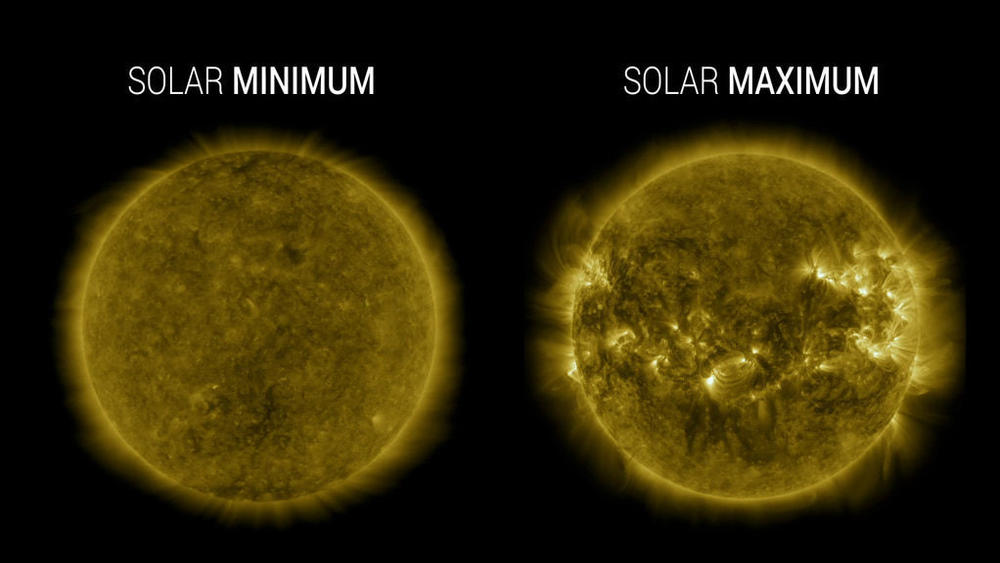

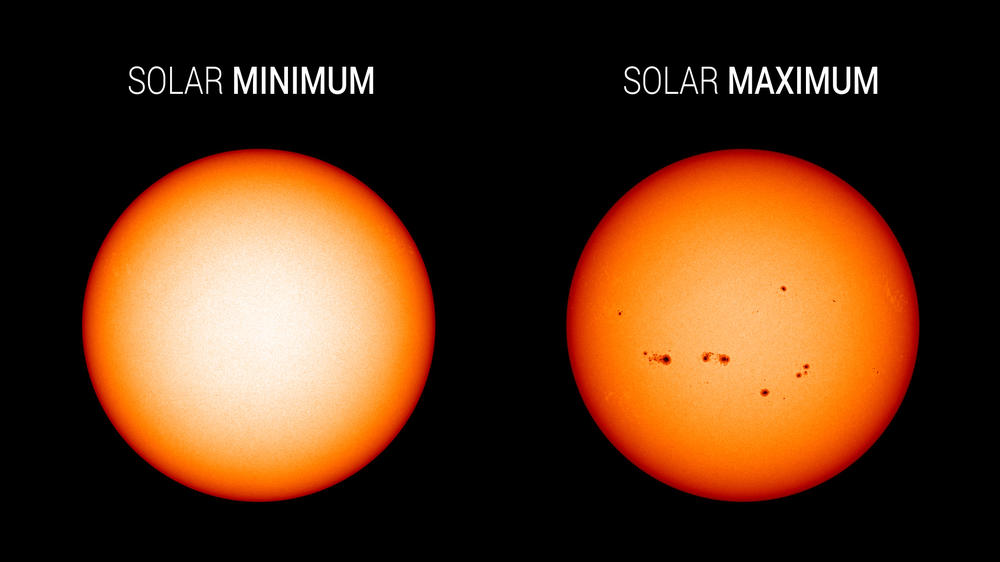

Over each solar cycle, the roiling sun moves from a relatively quiet period through a much more active one. Researchers monitor all this activity by keeping an eye on the number of sunspots, temporary dark patches on the sun's surface. These spots are associated with solar activity like giant explosions that send light, energy, and solar material into space.

Counting of sunspots goes back centuries, and the list of numbered solar cycles tracked by scientists starts with one that began in 1755 and ended in 1766. On average, cycles last about 11 years.

Based on recent sunspot data, researchers can now say that so-called "Solar Cycle 24" came to an end in December of 2019. Solar Cycle 25 has officially begun, with the number of sun spots slowly but steadily increasing.

A panel of international experts convened by NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has predicted that this cycle will reach its peak in July of 2025, and the intensity should be almost identical to the previous cycle, which was not very strong.

"The last cycle, Solar Cycle 24, was the fourth smallest cycle on record and the weakest cycle in 100 years," says Lisa Upton, a solar scientist with the Space Systems Research Corporation and co-chair of the Solar Cycle 25 Prediction Panel.

That panel of experts came to agreement on the forecast for the next cycle fairly quickly. "The consensus was very solid," says Doug Biesecker, a solar physicist at NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center in Boulder, Colo., who also served as co-chair.

He says solar cycle modeling has improved over the last decade or so, making it easier to make predictions. But still, the last time around, the group didn't do too badly.

"We were very close in predicting Solar Cycle 24. It was within what we consider to be our error bar of a sunspot number of plus or minus ten," says Biesecker. "We did get the timing of maximum wrong. And the reason for that was because we treated the sun as one big ball of gas, but the hemispheres, the south and the north, behave independently. The last solar cycle, they were out of phase with each other more so than ever before, which sort of ruined our forecast a bit."

Besides the obvious need to protect the electrical grid and other important technology infrastructures, government officials also want to understand space weather as they try to return people to the moon.

"A trip to the moon can include periods of time when our astronauts will not be protected from space weather by the Earth's magnetic field," says Jake Bleacher, chief exploration scientist in NASA's Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate. "Just like here at home when you go on a trip anywhere, you're going to check the weather report, right? You need to know what to expect."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.