Section Branding

Header Content

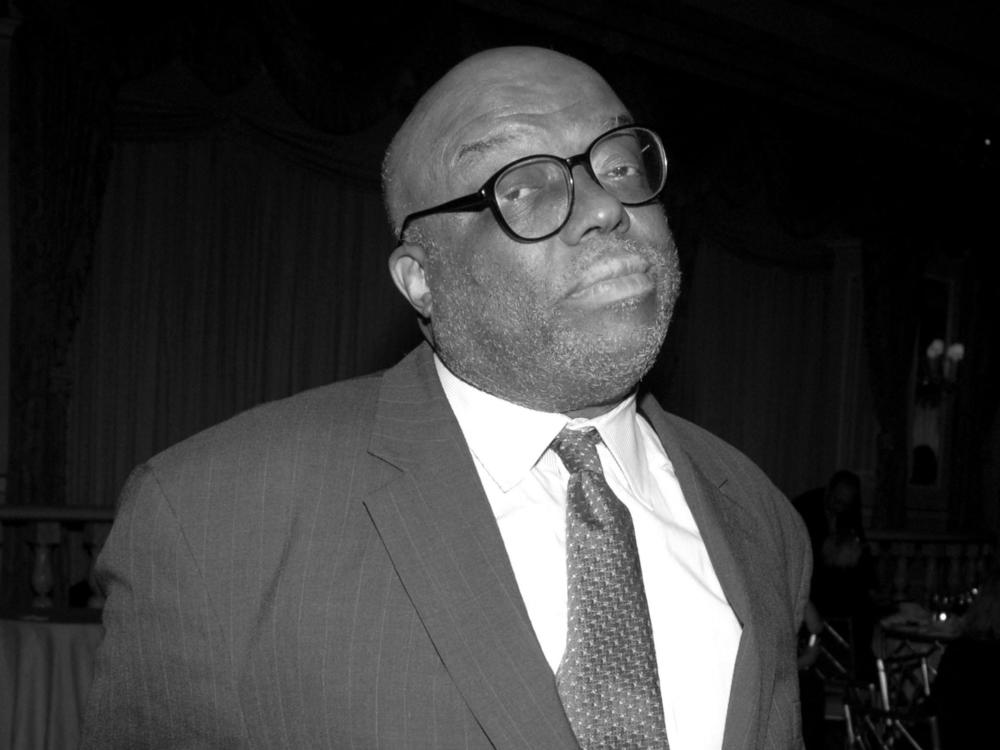

Stanley Crouch, Towering Jazz Critic, Dead At 74

Primary Content

Stanley Crouch, the lauded and fiery jazz critic, has died. According to an announcement by his wife, Gloria Nixon-Crouch, Stanley Crouch died at the Calvary Hospital in New York on Wednesday, following nearly a decade of serious health issues.

Crouch was born in Los Angeles on Dec. 14, 1945. He read voraciously, watched the Watts riots up close, took up jazz drums, published Black Nationalist poetry, led guerilla-theater troupes and taught literature at Pomona College, all before moving to New York in 1975 and becoming a cultural critic at the Village Voice. His first collection, Notes of a Hanging Judge: Essays and Reviews, 1979-1989, is a classic of American letters, with disquisitions on diverse topics like Jesse Jackson, filmmaker Ousmane Sembene and painter Bob Thompson, before wrapping up with a panoramic diary of the Umbria Jazz Festival in Italy. The volume got wide play, was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for criticism, and established Crouch as a force to be reckoned with. Later books included a novel, Don't the Moon Look Lonesome?, which received a close read from John Updike in the New Yorker, and a well-received biography, Kansas City Lightning: The Rise and Times of Charlie Parker. His many honors included a MacArthur Foundation "genius" grant and a NEA Jazz Masters Fellowship.

After publicly renouncing Black Nationalism in 1979, Crouch strove to place himself in the tradition of Ralph Ellison and, especially, Albert Murray, thinkers through which the idea of embracing Blackness and embracing American-ness became one and the same. Crouch felt he was extending Ellison's and Murray's work when attacking important artists, such as Spike Lee and Toni Morrison, for "doing the race thing." At the same time, Crouch fought for what he considered a Black aesthetic in jazz, and his 2003 JazzTimes essay "Putting the White Man in Charge" pairs neatly with Amiri Baraka's famous 1960 polemic, "Jazz and the White Critic." His outsized opinions were rendered in scalding, pugilistic prose – he even acquired a reputation for being willing to literally fight someone for disagreeing with him.

Unsurprisingly, Crouch became one of the most controversial commentators around, the sort of critic everyone had an opinion about, even if they had never seriously engaged with his work.

In the 2000s, I came to know Stanley well, read his complete collected essays (at the time, I decided The All-American Skin Game was his best book overall, with a marvelous central section commemorating Ellison as "the Oklahoma Kid" and praise for a trio of women, Barbara Probst Solomon, Martha Bayles, and Jackie Kennedy) and studied his relationship to jazz up close.

It's conventional for a memorial, such as this one, to be full of platitudes and generally respectful towards the departed. But the passing of Stanley Crouch is no occasion to be bland.

Black Codes

There's the music of jazz, and there's the text about jazz. It's always been a complex and unsatisfying relationship. The wonderful (and white) guitarist John Scofield apprenticed with great Black musicians; Scofield told me recently, "The Black musicians completely bypassed critics. That was 'Whitey' stuff: what did the critics know?"

During the great postwar era of small-group jazz, successful Black musicians mentored worthy young musicians into the profession, without much interaction with the critics one way or the other. (Some inscrutable form of internal gatekeeping kept giving notable talents a proper chance.) But, eventually, more and more words concerning the art penetrated into the music itself. Thanks to the rise of jazz education in the '70s, the market was flooded by basic instructional manuals coming from white institutions that had no racial awareness whatsoever. At the same time, novice critics found avant-garde jazz much easier to celebrate in print than music rooted in more traditional values.

Stanley Crouch played drums in California with Black Music Infinity, a sadly unrecorded group with David Murray, Arthur Blythe, James Newton and Mark Dresser. Bobby Bradford was another close associate. Even at that time, Duke Ellington was Crouch's lodestar, perhaps an unusual obsession for a young avant-gardist in the early '70s. (There was probably not a week in Crouch's adult life where he wasn't raving about Ellington to anyone in his immediate orbit.) After joining Murray and Blythe in New York, Crouch realized he wasn't going to make it as a serious drummer (although he sounds pretty good on a 1977 live date in Amsterdam with Murray) and focused on writing. For a time, Crouch booked the Tin Palace, a free-wheeling East Village club where Blythe, Murray, Newton, Henry Threadgill and other experimentalists rubbed shoulders with comparatively traditional players like George Coleman, Clifford Jordan, and Barry Harris.

In the mid-'80s, just as his career as a writer was reaching its first ascent, Stanley Crouch presided over an attempted, unexpected, coup d'etat. Crouch wanted to return to a time when the serious Black practitioners participated in the gatekeeping. (The title of a 2000 Crouch piece in the New York Times says it all: "Don't Ask the Critics. Ask Wallace Roney's Peers.") That was all to the good, but another, more reactionary and perhaps even more commercial aspect of his proposed revolution proved impossible to implement: defining jazz as a fixed object made up of conventional swing, blues, romantic ballads, a Latin tinge... and not too much else. While executing this maneuver, Crouch rejected — by some lights, betrayed — his original peer group of Murray, Blythe and Newton, and instead embraced the latest musicians intrigued by a comparatively straight-ahead approach. (Newton complained, "A stylistically dominant agenda in jazz is like bringing Coca-Cola to a five-star dinner!")

It was an artificial conceit to begin with, and Crouch was too contrarian and combative to lead a movement. However, he did have one important acolyte: Wynton Marsalis, the man anointed as the biggest new jazz star of the era. Marsalis studied the texts of Stanley Crouch and Albert Murray the way he did the music of Jelly Roll Morton and Louis Armstrong. In what may have been an unprecedented event, a major jazz artist actually read critics, and let those critics inform his music. (Crouch also contributed liner notes to the first run of excellent Marsalis LPs.)

Between them, Marsalis and Crouch kicked off the jazz wars of the '80s and '90s, an argument about tradition versus innovation, a tempest in a teacup that played out in all the major jazz magazines, in many mainstream publications, in bars and clubs everywhere – and in the end did very little good to anybody. (The day Keith Jarrett angrily invited Wynton Marsalis to a "blues duel" in the New York Times was a notable low point.) The 2001 Ken Burns documentary Jazz, which featured Marsalis and Crouch as both off-screen advisors and on-screen commentators, was the climactic battleground. People who love post-1959 styles connected to funk, fusion and the avant-garde are still very upset about Ken Burns' Jazz.

Still. When he started assembling the repertory institution Jazz at Lincoln Center in 1987, Wynton Marsalis was advocating for the primacy of the Black aesthetic at a time when the white, Stan Kenton-to-Gary Burton lineage dominated major organizations like the Berklee College of Music and the International Association of Jazz Educators. The music of Kenton and Burton has tremendous value, but their vast institutional sway and undue influence in jazz education is part of this discussion. We needed less North Texas State (Kenton's first pedagogical initiative) and more Duke Ellington in the mix, and Marsalis almost single-handedly corrected our course – although Marsalis himself would give Crouch a lot of the credit. Indeed, Crouch's long-running internal mandate to get Ellington seen as "Artist of the Century" had finally paid off on a macro level, and the free high school program "Essentially Ellington" is one of JALC's most noble achievements.

Crouch and Marsalis also strove to bury the once-prevalent idea that Louis Armstrong was an Uncle Tom, and encouraged the Black working class to reclaim the jazz greats as crucial to their heritage. (Those ready to hate on Ken Burns's Jazz should keep that perspective in mind.)

There was some bad, a lot of good, and plenty to argue about. What can be said for sure: JALC never quite pulled off Crouch's proposed coup. All these years later, JALC remains merely a part of what makes jazz interesting today. Younger practitioners and listeners comfortably see the music as a continuum that can contain anything from the avant-garde harp musings of Alice Coltrane to the electric fusion of John McLaughlin to hip-hop stylings of Robert Glasper. Crouch's definition of jazz does not dominate the conversation the way he intended, perhaps paradoxically proving the original point that jazz musicians and critics don't really have much to do with each other.

The Hero and the Blues

Stanley Crouch's writing about jazz was in a class of one: technically accurate, poetic and always highlighting African-American ideals concerning rhythm, texture and the blues. While many of Crouch's most serious detractors have never bothered to read his work with an eye to discovering value, most serious jazz critics working today can bond over a "Stanley Crouch moment," an occasion when Crouch's prose broke through and electrified their studies.

Considering Genius: Writings on Jazz collects standalone pieces first seen in the Village Voice, The New York Times, JazzTimes and other places. But just as good, and certainly deserving of an anthology, are Crouch's insightful liner notes, which are about 100 in number.

From Old and New Dreams (1977):

[On Charlie Haden] "His connection to the tradition comes through Wilbur Ware and Percy Heath, both of whom have thick, dark sounds. Haden is one of the most percussive of bassists and resonates his sound against the ensemble with tenacity and swinging fire."

From Miles Davis, Live at the Plugged Nickel (1982):

"[Louis] Armstrong's quarter notes, quarter-note triplets, and long tones not only swung, they magnetized the rhythm of the whole band ... Both Lester Young and Billie Holiday heard what Armstrong had done and created their own identities ... Deep thinker that he was, Davis adapted their creations with such originality that he invented his own intensity, a force that would avoid the compulsive spewing of those who quickly made bebop into a predictable and rhythmically limited style."

From Introducing Kenny Garrett (1984):

"Garrett is from Detroit and plays the alto saxophone, a horn that has lost much of its position in jazz with the rise to celebrity and remarkable influence of John Coltrane, the most imitated innovator of the last twenty five years. But there are those who think the alto was as much avoided as ignored, since it is a much harder saxophone to get a pleasurable sound out of, to play in tune, and to keep under one's control. As many reed players have said, the alto is an instrument that has the stand-off qualities and the resistant fury of a stallion that dares you to break him."

The Garrett liner notes give a lot of space to Garrett himself, and at some point Crouch realized that quoting the musicians was one of the best ways to make his argument. Many of the pages inside Considering Genius are peppered with wisdom from serious practitioners, including a few unlikely sources, such as dedicated avant-gardist Anthony Braxton:

"Anthony Braxton once said to me that Connie Kay 'had fifty ways to play 4/4.' While I am not sure that fifty is an accurate number, the last time I heard Kay with the Modern Jazz Quartet, at the Carlyle Hotel, he approached 4/4 time from so many angles, mixing shuffle grooves, gospel beats, and something from the Caribbean. He did all of this while playing with so much control that the unmiked piano, vibraphone, and bass were perfectly audible throughout."

In some cases, great musicians may have shared their stories with Crouch simply because Crouch was Black. His biography, Kansas City Lightning: The Rise and Times of Charlie Parker, offers unique insights from musicians like Gene Ramey, Buster Smith and Jay McShann, not to mention a major contribution from Bird's first love and wife, Rebecca Ruffin.

Kansas City Lighting was a crucial entry in the annals of Charlie Parker reception, but it may be just shy of a masterpiece. Crouch loved the idea of the heroic, and painted that heroism with strokes of deeply purple prose. In the end, Crouch's take on Bird may just be a little sentimental. A similar charge might be leveled at Good Morning Blues, the book Count Basie wrote with Crouch's great mentor, Albert Murray.

One hopes that the interview tapes Crouch made with long-deceased greats are preserved and might be made available some day. As we get further and further from the years when jazz was at its height, the information known internally by the Black community — and more or less ignored by so many then-important white writers — only takes on greater and greater importance.

Memories of the Hanging Judge

My first sighting was at an afterparty, following the Lincoln Center concert Dewey's Circle in 1992. (Later on, I learned that this concert, honoring Dewey Redman, was Stanley's idea.) I got into the party via Karl Berger, who was then my landlord, and somehow ended up listening to Stanley lecture a few people about how Frank Sinatra couldn't sing in tune, at least not compared to someone like Ella Fitzgerald. I cheekily broke in and asked, "Does Billie Holiday sing more in tune than Frank Sinatra?" Stanley gave me the dirtiest of dirty looks and said, "No. But nobody can swing harder than Billie Holiday."

Fast forward a decade later: I was beginning to become a regular denizen at the Village Vanguard, going to many concerts, and even performing there, occasionally. At the time, Stanley was living a block away from the club, and more often than not he'd drop in to hear what was happening. I noticed that Stanley seemed pretty approachable. He'd talk about jazz to anybody.

Reid Anderson was gigging there with somebody else at the time. Stanley liked Reid's playing, and told him so. Later that night, Reid saw Stanley paging through a jazz magazine backstage. When Stanley came to an advertisement for the Bad Plus, Stanley stopped short and said to the room, "These sad motherf******." Reid shot back, "Hey, Stanley — that's my band." [Ed. note: Also the band of Ethan Iverson, writer of this piece.] Stanley's jaw dropped open in shock.

I heard about this later from Reid, of course, so the next time I saw Stanley at the club I joined him at a table. I introduced myself and he grunted a chilly hello. We were listening to Mark Turner, Larry Grenadier and Jeff Ballard. At one moment, Mark was playing something really abstract and beautiful, high on the horn, while Larry and Jeff were holding down a groove. Stanley leaned in and told me, "Funny how the Black guy sounds whiter than the two white guys."

I gave him a deadpan look and responded, "I thought that Albert Murray said that all Americans were neither Black or white, but a mixture of both."

From that moment, we were tight. For four or five years Stanley and I were in constant contact, endlessly discussing jazz and other matters. It was part of the fairytale I lived, being in a successful band, meeting my heroes, walking the streets of New York like I actually belonged there. The first time I took Stanley to lunch, he was stopped on the sidewalk by Wallace Shawn, who said something to the effect of, "Stanley, I loved your latest Daily News column and thanks for all you do." Stanley was casually gracious and made no further comment about random praise from a celebrity. Yeah. This was real New York stuff.

Stanley was a great writer, but he might have been an even greater talker. His monologues were florid improvisations. A single prompt brought forth a cascade of insight.

A particularly memorable example concerned Roy Haynes. My wife, Sarah Deming, had also become friends with Stanley. (He told me straight out, "My respect for your sorry ass increased after I learned how cool your wife was.") Stanley would talk jazz with me and boxing with Sarah.

For a year in 2007, Sarah was the New York City brand attaché for Grey Goose, which meant she could expense fancy dinners, as long as her table asked for the vodka by name. (Talk about living in a fairytale.) Sarah took us to Masa for Stanley's birthday, where we ate and drank like Roman emperors. We followed that up with an unsteady stroll over to Birdland, for the second set of the Roy Haynes quartet. The music started and Stanley fell asleep, slumped over in his chair. (Truthfully, after all that food and booze, I was about in that kind of shape myself.)

After the first song, Haynes went to the microphone and said, "I heard Stanley Crouch is in the audience tonight. Stanley! Come up here and tell the audience about how great I am!"

I hurriedly woke Stanley and sent him to do Haynes's bidding. His posture straightened up as he magisterially approached the stage. In full control of the room and the mic, Stanley delivered an impromptu ten-minute lecture on the greatness of Roy Haynes. It was a flawless performance.

Discussing jazz with Stanley was a fabulous education. He had heard everything and knew about it all. When I got off the bandstand one time with Ben Street and Nasheet Waits as Smalls, he said by way of greeting, "F*** Lennie Tristano." That didn't mean he didn't respect Tristano, though: Stanley praised Tristano, Warne Marsh and Lee Konitz in print. (When together, Lee and Stanley would josh with each other like nobody's business.) Rather, Stanley was warning me not to sound too much like Tristano in my own playing, which may have been valuable practical advice.

There was also the time Stanley dissected Keith Jarrett, specifically what Stanley thought Keith really could and couldn't do as a blues player. That was an interesting conversation. I wish I'd had the tape recorder going.

Another of Stanley's passions was the cinema. Quentin Tarantino was impressed by Stanley's perceptive review of Pulp Fiction, and asked Stanley to accept Tarantino's award by the National Board of Review. (Typically, Stanley later denounced Tarantino's Django Unchained as, "One of the worst versions of Blaxploitation ever seen.") After watching The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance at BAM, I immediately called Stanley, who gave me an hour-long rundown on John Ford, Jimmy Stewart, John Wayne, Vera Miles and Lee Marvin. Again, that would have been a good one to have been recorded, although Stanley did write about John Ford and Westerns on more than one occasion.

As it turned out, most telephone conversations with Stanley were an hour. Usually, an hour-long monologue. Glenn Gould exhausted friendships by calling and talking and talking and talking. More than one person fell asleep listening to Gould drone away on the other end of the line. In this respect, Glenn Gould and Stanley Crouch were peas in a pod.

An early interview for my blog, Do the Math, was with Stanley in 2007. I work to produce literary documents: after the interview, the interviewee has a chance to edit the text and make sure they are saying exactly what they want for the official record.

Usually, the interviewee softens their language, which is only correct. In the moment, you talk big; in the cold light of print, you tone it down.

At this point, there have been almost 50 DTM interviews. There is only one person who made their written statement more aggressive than their casual conversation. I couldn't believe it when I got the text back – Stanley had doubled down on insults and polemic. It was a real insight into his style. I omitted most of that stuff before posting, not wanting to go down with the ship.

I'm not sure why Stanley felt he needed to be so attacking in print, especially since his intimate conversation could be so relaxed and humane. Perhaps it was because he was a self-made man, someone who came from a low rung of society and made it all the way to being a household name in American arts and letters simply through intelligence and force of will. At any rate, he rang that string out, burning bridges his whole life. Unrepentant. Unbowed.

It's probably good for everybody that he stopped producing work as the age of social media picked up its pace. When I raised that point to WBGO's Nate Chinen a few weeks ago, Nate responded, "Yeah. Stanley would've been canceled more often than a New York Times subscription."

On the other hand, I already miss having a voice in the choir that was sure to rile somebody.

After he moved into the Hebrew Home at Riverdale, I visited him one last time with Aaron Diehl and Sarah. When he saw me, Stanley immediately launched into a dissertation on why Bud Powell was so much greater than Oscar Peterson. For a few minutes, it was perfect... but then cracks began to show, his talk started to run off the track. It was truly terrible to see this great mind lose its way.

Still, he was a fighter to the end. After contracting COVID-19 in the spring, he shook it off, grasping to life for a few more months.

The written record will always be slightly askew with Stanley, for if you knew him in person, it was impossible not to love him. He was a sharp-tongued devil but he believed in humanity and in progress. He signed every correspondence with his trademark "V.I.A.," standing for: "Victory Is Assured."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content