Caption

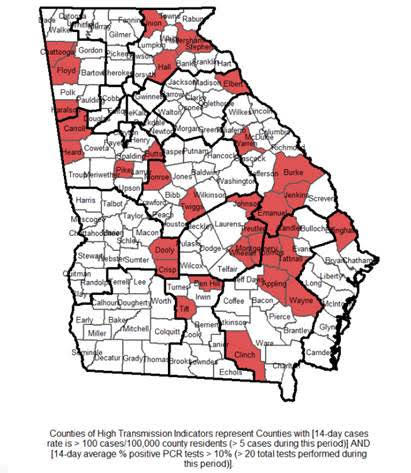

Dr. Karen Kinsell, a physician in rural Clay County, in southwest Georgia said, “Large numbers of people cannot afford health care or cannot get it because it is too far away or closed when they can go.’’

Credit: Georgia Health News