Section Branding

Header Content

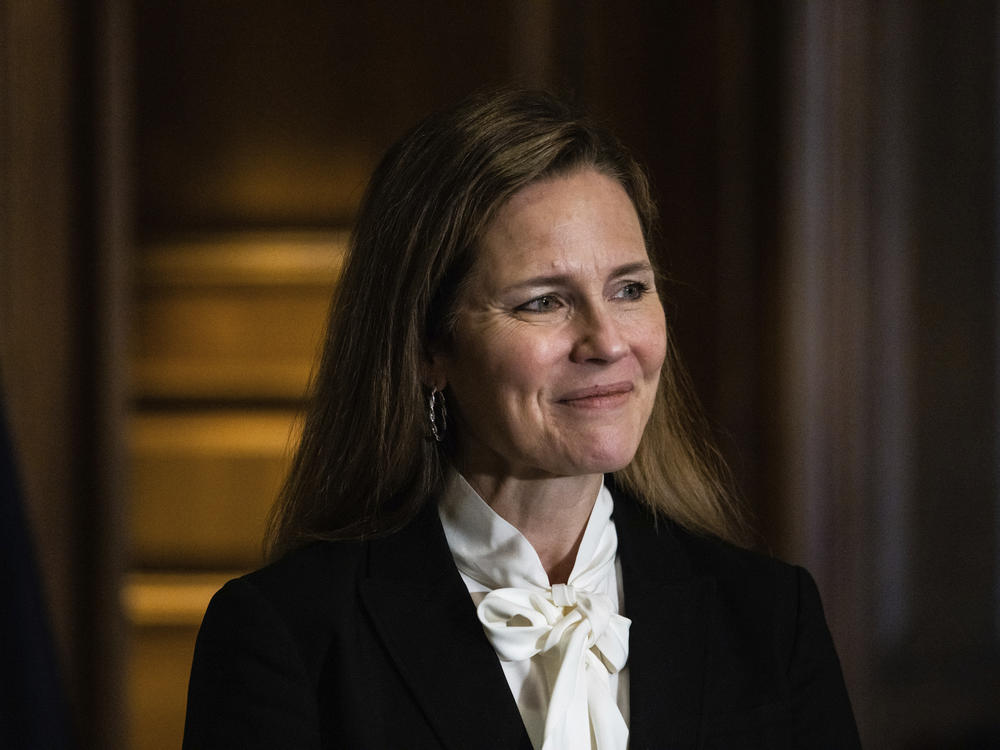

How Trump's Supreme Court Pick Might Hinder Climate Action

Primary Content

Environmental law likely won't get the same attention as abortion or health care at next week's Senate hearings for Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett. But her confirmation, tilting the already-conservative court even further to the right, could have a major impact on the government's ability to address climate change.

Nearly all of President Trump's climate rollbacks have been challenged, and several are likely headed to the high court. And some conservative allies with ties to the fossil fuel industry say they'd like to relitigate a key decision that underpins climate regulations.

It's difficult to predict how Barrett would rule on specific cases. Environmental law was not her focus as a professor, and not something she dealt with a lot during her time on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit.

Her judicial philosophy does offer clues. She discussed that when her nomination was announced.

"A judge must apply the law, as written. Judges are not policymakers and they must be resolute in setting aside any policy views they might hold," Barrett said at a White House Rose Garden event last month.

Barrett's judicial philosophy shows skepticism of government and favors deregulation over regulation, according to Jody Freeman, who directs the Environmental and Energy Law Program at Harvard Law School and also served in the Obama administration.

"I think, generally speaking, it's going to be a corporate court — good for business, good for corporations," says Freeman.

Barrett is skeptical of federal agencies stretching their authority under laws where Congress hasn't given them clear direction, but Freeman says agencies need flexibility.

"Even when Congress passes new laws there are always ambiguities," she says. "There always is new science, new understandings, new risks, new problems, new data. And it's impossible to specify each and every small decision that the agencies make."

And sometimes agencies have to use existing laws to address new problems, like climate change. That's what the Obama administration did after failing to convince Congress to pass legislation focused on the polarizing topic.

The Environmental Protection Agency turned to the decades-old Clean Air Act to regulate greenhouse gases under Obama's Clean Power Plan. A 2007 Supreme Court case, Massachusetts v. EPA, determined carbon dioxide could be regulated under the act. It's become an important environmental ruling, and now some worry a more conservative Supreme Court could overturn or weaken it.

Case Western Reserve University law professor Jonathan Adler thinks that's unlikely to happen on the question of whether greenhouse gases are a pollutant. But he sees more of a chance on the constitutional issue of standing — that is, whether Massachusetts and other states can show the direct injury that gives them the right to sue the federal government in the first place.

"Standing on climate cases can be a challenge, and I think based on what we've seen on the 7th Circuit, a Justice Barrett certainly won't make that challenge any easier," says Adler, who also directs the Coleman P. Burke Center for Environmental Law.

Adler, a conservative, agrees that Barrett is skeptical of agencies overreaching their authority. But he says that doesn't mean Barrett is hostile to addressing climate change, just that Congress needs to pass more specific laws.

"Congress doesn't do a lot of that these days," he says. But "I'm old fashioned, in that I think that's what we elect members of Congress, and that's what we elect senators, to do."

This appeals to conservatives like Tom Pyle with the American Energy Alliance, who supports Barrett's nomination and said on his podcast Unregulated, "Let's duke it out where it belongs, in Congress."

But Reverend Lennox Yearwood Jr. with the Hip Hop Caucus. says he wants a different kind of justice who will lead on fixing big problems like climate change.

"It is a lifetime position," he says, and requires someone who "understands the nuances of the world that we live in today."

He's among those who want the Senate to wait on a confirmation vote until after the presidential election.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.