Section Branding

Header Content

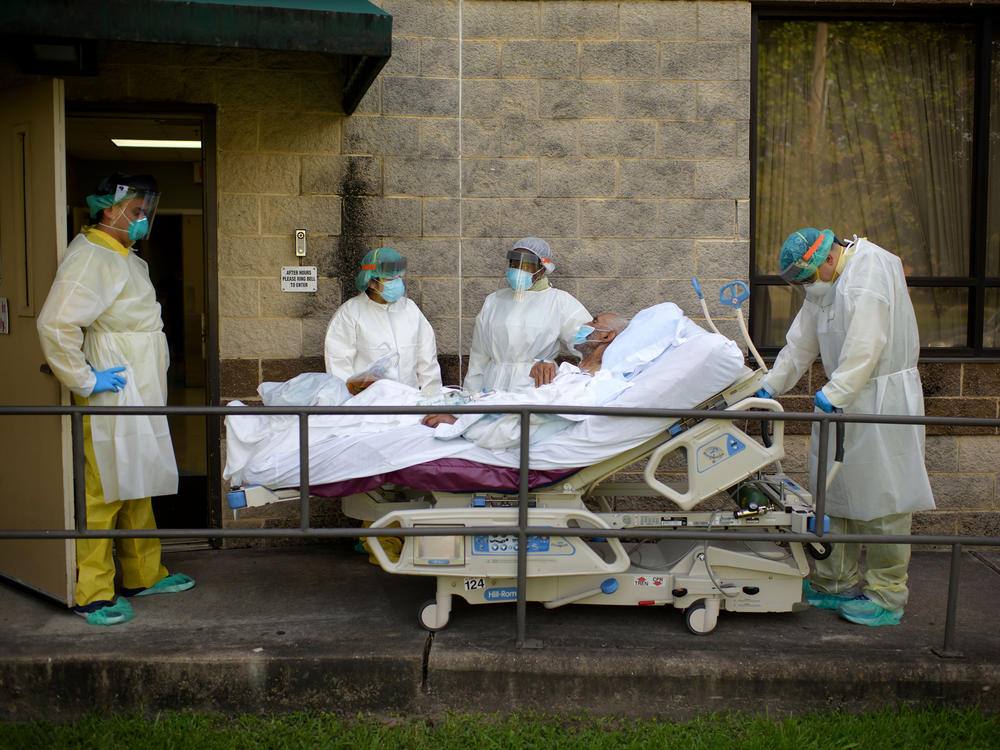

What's Coming This Winter? Here's How Many More Could Die In The Pandemic

Primary Content

Coronavirus cases are rising rapidly in many states as the U.S. heads into the winter months. And forecasters predict staggering growth in infections and deaths if current trends continue.

It's exactly the kind of scenario that public health experts have long warned could be in store for the country, if it did not aggressively tamp down on infections over the summer.

"We were really hoping to crater the cases in preparation for a bad winter," says Tara Smith, a professor of epidemiology at Kent State University. "We've done basically the opposite."

After hitting an all-time high in July, cases did drop significantly, but the U.S. never reached a level where the public health system could truly get a handle on the outbreak.

Now infections are on the rise again.

The U.S. is averaging more than 52,000 new cases a day (the highest it's been since mid-August), driven by ballooning outbreaks across the country's interior, especially in the Midwest, the Great Plains and the West

Contributing to this rise is the return of students to campus, resistance to mandates on social distancing and mask wearing, and more people spending time in restaurants and other indoor settings, Smith says.

Dr. Michael Mina, a professor at Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, compares the situation to a growing forest fire with small sparks all over the U.S. that will gain strength as the weather turns colder.

"We are likely to see massive explosions of cases and outbreaks that could potentially make what we've seen so far look like it hasn't been that much," says Mina.

Nearly 400,000 deaths by February?

A forecast from one of the country's leading coronavirus modeling groups projects more than 170,000 people could die from COVID-19 between now and Feb. 1, bringing the pandemic's overall death toll to nearly 390,000.

"Unfortunately, in the United States, it's still the first wave of the outbreak," says Ali Mokdad, professor of health metrics sciences at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, which developed the model.

The model forecasts three different scenarios to reflect the potential impact of policies and people's behavior on outcomes. The worst assumes social distancing mandates continue to be rolled back — and projects nearly 483,000 cumulative deaths by Feb. 1. The rosiest scenario assumes communities reimpose such mandates when deaths reach a certain level per capita and that nearly everyone wears masks. In that case, cumulative deaths could still reach nearly 315,000.

Currently the U.S. averages over 700 deaths a day. IHME projects it could rise to more than 2,000 a day by mid-January, rivaling the most fatal days in the spring.

So far, Mokdad says the data clearly show the U.S. is stuck in a reactive cycle: when cases spike in their community, people change their behavior significantly — they stay home more and wear masks, even in places where it's not required.

Once the situation improves, people return to their previous behavior.

"We are on like a roller coaster in every location in the United States," says Mokdad. "We bring cases down, then we let down our guard. But this is a deadly virus — you cannot give it a chance to circulate."

And cold weather could play a role. In the Southern hemisphere, countries saw a rise in cases in the recent cold months, even with a lot of social distancing and many people wearing masks, says Mokdad, which indicates that "there is a seasonality factor" with COVID-19 that mimics pneumonia.

High levels of circulating virus

Even places that have already come back from devastating outbreaks remain vulnerable to a resurgence over the winter, says Lauren Ancel Meyers, a professor at the University of Texas, Austin who directs the University of Texas COVID-19 Modeling Consortium.

Meyers notes that even in Texas — a state where a summer surge helped drive the cumulative death toll to more than 17,000 — the virus is much more widespread than it was during the spring. This is true in many parts of the country.

"Even though things look sort of flat from the perspective of which way the trends are going, the level at which we're flat is still an awful lot of virus circulating in our communities," she says, although the hope is those communities may be more responsive now to taking precautions if cases spike.

Her group's model currently projects a cumulative 234,684 deaths by Nov. 9, but does not look any further ahead.

"We understand so much about how this virus spreads," says Meyers. "What we don't know is what behaviors will be and what decisions people will make in the coming months."

That projection is similar to what researchers at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst predict in the COVID-19 ForecastHub, an "ensemble model" merging more than 30 different COVID-19 models.

It predicts about 234,633 total deaths by Nov 7.

"There are sort of opposing forces that are acting on what we might see," says University of Massachusetts, Amherst professor Nicholas Reich, whose lab runs the ensemble model.

"On the one hand, we know that people will be spending more time inside and that has the potential to increase transmission," he says. "On the flip side, people are in general being more careful."

But Reich says there are just too many uncertainties to forecast beyond a month: "In my mind, that's sort of the limit of reliable predictability," he says.

The choice

While the U.S. outbreak can be described as having different "waves" — one in the spring, another in the summer — public health experts say that does not fully capture how the pandemic has washed unevenly over the country throughout the year.

"A better way of thinking about it is a wave that went into a pool and in that pool it's sloshing around," says Dr. Roger Shapiro, a professor at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. "Wherever it hasn't been yet, it's going to go, and the place where it has already been it could go back."

Estimates vary, but the vast majority of the U.S. population has not been infected, which means most communities are still at risk of big outbreaks, he says.

Strict adherence to mask wearing and decreasing indoor gatherings could help avert the worst wintertime COVID-19 scenarios. But it's not certain that community leaders have the political will to impose such restrictions.

Mina says he anticipates states will continue to open up just as transmissibility of the virus increases and more people spend time inside, creating "a perfect storm."

"Will it be that we close down again fully?" Mina asks. "Or will it be that we choose a lot of infections? If that's the case, we still haven't done a really good job at figuring out how to keep vulnerable people safe."

But COVID-19 modeler Nicholas Reich notes the dire predictions are only that — our best guess. He says the winter could look very different if Americans take precautions seriously.

"The optimism that we can take from this is that human behavior can change this," he says. "We can bend and flatten the curve."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.