Section Branding

Header Content

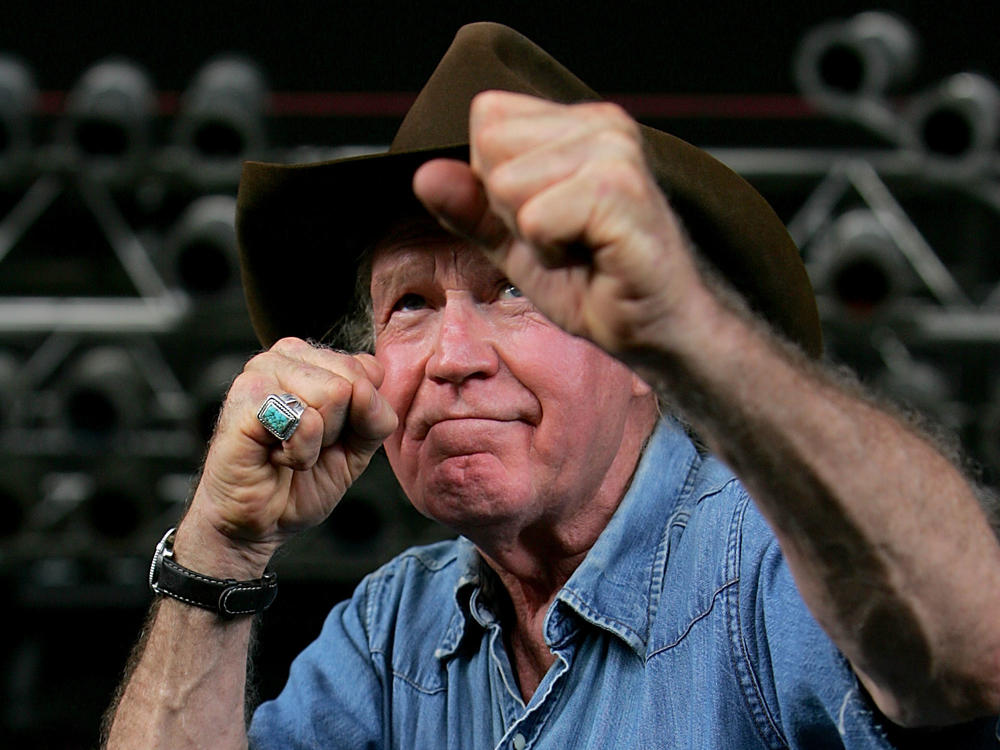

The Ballad Of Billy Joe Shaver And Jerry Jeff Walker, Country Outlaws

Primary Content

The world, by way of Texas, lost two of its most iconoclastic, deservedly mythologized artists this past month – Jerry Jeff Walker, songwriter-flâneur-buckaroo; and Billy Joe Shaver, ornery and God-fearing ghost poet of America's scorched earth.

Jerry Jeff, 78, succumbed to complications from throat cancer on October 23; Billy Joe, 81, suffered a stroke and relocated to Heaven five days later.

Dispositionally, the two men were no simpático. It wouldn't have taken much for moody goofball aesthete Jerry Jeff, a self-invented Texan born Ronald Clyde Crosby in Oneonta, N.Y., to work the last gnarled nerve of Billy Joe, a short-fused, dirt-poor refugee from an East Texas ex-oil town. But both were gripped by a deeper desire to rouse the buried spirit of a saddened country's music, to paraphrase the Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca's "Theory and Play of the Duende."

Cut to wholly believable fictional scene: Jerry Jeff is carrying on about the length of his houseboat in Key West or his love of Dylan Thomas' verse and Shaver, feeling duty-bound to save everybody from a Hogzilla-sized cringe, inserts his fist in the Yankee imposter's mouth hole to stem the tide of B.S. You can bet that somewhere, in the swirl of beer, blood, spittle, pride and warring lyrical sensibilities, a great song was percolating.

In their half-century on the grind, neither artist left a particularly visible commercial footprint, but they cast a vast cultural shadow. Preternaturally gifted storytellers and advanced-level interpreters of their own and others' songs, the two men alternately obliterated or plowed through genre boundaries (folk, rock, blues, jazz, conjunto, Tejano) and gained the trust of disparate, adversarial fanbases. More than any other figures, they embodied the Austin, Texas-based hippie honky-tonk upheaval of the '70s, variously marketed as "cosmic country," "progressive country," "redneck rock," "gonzo country" and, most commonly, "outlaw country."

Whether you called it a movement, genre, or radio format (Austin radio station KOKE was a key ally), outlaw country had an unmistakably hot-wired sound, like a multi-generational melodrama in progress – desperate voices cutting like rusty knives across yawping, cooing country and rock-and-roll instrumentation that could scratch off in any direction. There were young hippies and freaks in the South and Southwest during the 1960s, but they were badly outnumbered and, literally, outgunned. Now, in the early '70s, that tide was turning and the so-called outlaws were struggling with the absurdly contradictory legends and institutions of America, artistic and otherwise, right out in the open.

The '70s outlaw scene in Texas gathered together an unprecedented constituency. Cranked-to-the-gills bikers bumped uglies with blissed-out, barefooted longhairs. Booted-and-buttoned-up ranchers and farmers navigated hellbound University of Texas frat boys and jocks, ramrod adherents of Nashville fantasia twang, a burgeoning class of upwardly mobile professionals with paper to burn, and a contingent of Republican and Democratic riff-raff filtering over from the state-government compounds.

The room where this unholy congregation assembled was Armadillo World Headquarters, an abandoned armory tucked behind a south Austin roller rink, with a capacity of 1,500 patrons. (The cavernous space was exalted in "London Homesick Blues," written by Jerry Jeff sideman Gary P. Nunn and later known as the theme song of PBS series Austin City Limits.) The relatively nonviolent triumph of the Armadillo's outlaw social experiment (which ran from 1970-80) was, in terms of evolutionary spectacle, akin to the Apollo spacecraft's safe landing on the moon.

Jerry Jeff's route to Armadillo World HQ was a maze of fits and starts throughout the '60s. A high-school basketball star in upstate New York, Ronald Crosby hitchhiked south through Virginia, Florida, Louisiana and Texas, back up to New York and then back down to Houston, where he co-founded druggy, psych-folk quintet Circus Maximus (named after the Armadillo HQ of ancient Rome) before again returning to New York. The band recorded two albums of effects-laden headscapes in 1967-'68 on Vanguard Records, dialing up the velvety jazz-rock pretensions of the Moody Blues. Dissatisfied, he exited the Circus, shuffled through his fake-ID stage names – Jerry Ferris, Jeff Walker, Happy Guitar, Jerry Walker – and finally went full folkie as "Jerry Jeff Walker," working the same Greenwich Village circles as next-big-thing Joni Mitchell and unknown neophyte Emmylou Harris.

Suddenly, in 1967-68, Jerry Jeff banked himself a lifetime pass of legitimacy and royalties by concocting a bona-fide American standard, "Mr. Bojangles." An empathetic, hypnotic 6/8 waltz inspired by a homeless white minstrel he'd met in a segregated New Orleans drunk tank in 1965, the song was a Top 10 hit for the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band in 1971, inspiring a spate of covers by, among others, Nina Simone, Neil Diamond, U.K. pop star Lulu, cigar-chomping comedian George Burns and Jamaican reggae crooner Dennis Brown.

But it was Derby-hatted Sammy Davis, Jr.'s preambling, whistling, everything-but-jazz-hands, soft-shoe croon that emerged as the song's quintessential expression. Davis recast and blurred the scene so that the countless, fabulously talented Black song-and-dance men who made it or didn't or never got the chance, fused into one dazzling, betrayed, proud figure tossed in jail or left for dead, much like the real-life Bojangles, the minstrel and vaudeville tap dancer/singer/actor Bill Robinson, who was the highest-paid Black entertainer of the 1930s and '40s, but died penniless. Davis, whose stardom depended on the tenuous largesse of white benefactors, constantly feared being relegated to the streets himself. He identified with the song so strongly that it gained a vaguely Civil Rights tinge.

Despite the boost that "Bojangles" gave its songwriter, the following years were a struggle for Jerry Jeff Walker – now a professional, if still nomadic, folkie. Moving between New York, Nashville and wherever he fell asleep, Walker recorded four amiable, fairly subdued albums from 1968 to 1970. They featured a smattering of memorable self-written songs ("Little Bird," "Maybe Mexico," "My Old Man," "Janet Says") and notable covers (the gorgeously heartrending "About Her Eyes," by Kentucky-born Village folkie Keith Sykes); but it wasn't until Jerry Jeff finally adopted Austin, Texas and the Hill Country west of the city as his home that the muted light around him really started to crackle.

His coming-out party as a "Buckaroo" (the unofficial term of address for his devotees from here on) was 1972's Jerry Jeff, an accidental outlaw manifesto and American music's great backyard fish fry. A stretch of unburdened warmth and joy, led by a guy blooming into the utmost version of himself, the album hums from the git-go, live and limber in the studio (hollers, asides preserved). The ambience is informal, the focus is not.

Jerry Jeff's originals were an exponential leap forward – the thrilling, hey-y'all call to worship "Hill Country Rain"; "Charlie Dunn," an intimate ode to the local sage who mentored the transplanted Yankee in the cowboy-boot arts ; the sunny-then-bawdy blues-gospel swoon of "Her Good Lovin' Grace" and "Hairy Ass Hillbillies." His covers of Guy Clark's magnificent, yet-to-be-canonized songs ("L.A. Freeway," "Desperados Waiting on a Train," "That Old Time Feeling") were breathtaking, immaculately fitting Jerry Jeff's new persona as the winking, big-hearted, seen-it-all scamp, everybody's fatally flawed confidant. The versatile, self-directed, often incandescent crew of musicians who became Jerry Jeff's invaluable Lost Gonzo Band are kept between the lines by a crew of intuitive session pros.

Organically rolling and roiling like a storefront church's all-day revival meeting, the album was officially produced by Jerry Jeff's manager Michael Brovsky. But I like to imagine that the music was goaded on by the presence of a vaquero-obsessed duende – the sly, fiery, folkloric spirit that Lorca extolled as the combative, creative force behind the elemental tremble of Andalusian Spain's Gypsy or flamenco singers, dancers and musicians.

Interestingly, the first track on Jerry Jeff's first album was "Gypsy Songman," an entry in the humble-brag school of musical crowd work: see "I'm Just an Old Folk Singer," "I'm Just a Song and Dance Man," "I'm Just a Singer (in a Rock'n'Roll Band)." Putting aside that a generic "Gypsy" reference is now rightfully considered a slur (especially from a white man), and despite guitarist David Bromberg's subtly dizzying flecks of color around Jerry Jeff's melancholy lilt, the song was not possessed of duende's feisty grit. Gypsy songman? More like: young man on a flying trapeze who didn't get paid enough for "daring."

Jerry Jeff's engaging, out-of-print 1999 autobiography was also called Gypsy Songman. (Please, somebody, re-release it with a new title; the cheapest copy available last I checked was $269.84 on eBay). Regardless, at least with the book, we knew that the peripatetic 57-year-old bandleader, father, husband and self-sufficient hustler (Tried and True Records, run by his wife Susan) was selling stories of hard-won experience.

Of course, many of Jerry Jeff's life-lessons came from self-inflicted wounds: rampant property and psychic damage from substance-abusing flourishes; monstrous vehicular chaos, highlighted by approximately 25 drunk-driving arrests by the end of the '70s; a substantial IRS boo-boo; and much more. Perhaps most stinging of all, he had to opt for cosmetic repair on his distinctive Roman nose after countless bar fights and too many all-nighters spent inhaling rails of powder like gulps of oxygen (wags called him "Mr. Blowjangles" and "Jiffy Jack Snowdrift"). He minimized the antics by claiming he was "stirring the Gonzo stew." Yes, he had frequent playdates with Hunter S. Thompson.

But... what if he was just getting real, real gone with the duende?

Lorca wrote: "[The duende] won't appear if [the artist] can't see the possibility of death, if [the artist] doesn't know [they] can haunt death's house." Also: "[The] duende wounds, and in trying to heal that wound that never heals, lies the strangeness, the inventiveness of [an artist's] work." Whether or not you buy the linkage now, given time I bet I could convince you that the duende's darkly anarchic impulse is all over Jerry Jeff's best work. From 1972 to 1978, say, when he released nine albums and played up to 200 shows a year.

In further front-page outlaw news, Nashville vet and native Texan Willie Nelson moved to Austin in 1972, performed to tinderbox crowds at the Armadillo and imbibed the outlaw elixir. He got a taste for Jerry Jeff's spontaneously sideways aesthetic, spotlighted to its fullest on the 1973 hit live album ¡Viva Terlingua!, recorded in a remote Hill Country dance hall with hay bales for sound baffles. The seat-of-the pants, communal mythos of Terlingua's process was just as important as the product. Nelson wanted in, throwing a local, three-day music festival and rejiggering his entire music-making approach.

Billy Joe Shaver and Waylon Jennings both played that festival, dubbed the Dripping Springs Reunion, and at some point Jennings heard the loping, picaresque Shaver tune (that word again!), "Willie the Wandering Gypsy and Me." It was as if a Cormac McCarthy epic had been wholly distilled to a hieroglyph scrawled on a matchbook. Like Nelson, Jennings was a Texas native and bored Nashville baller giving the Austin scene a once-over. Craving inspiration, he wondered if the outlaw shtick could reinvigorate his energy.

Playing a hunch, Jennings went full bore, covering nine Shaver songs for 1973's Honky Tonk Heroes, now widely considered his fiercest, most focused album statement in a recording career that spanned five decades. Austin rocker and Texas Monthly writer Michael Hall called It the Never Mind the Bollocks, Here's the Sex Pistols of outlaw country. Waylon, now clad in black leather, had a fresh edge; and Shaver's unwavering belief in his own unrecognized genius had been validated. His songs were viewed as precious gems, acquired by everyone from Elvis to the Allman Brothers.

Shaver did not coast on his peers' respect. He continued to spool out tersely panoramic songs like sacred, dusty scrolls, but pursuing a country singing career while simultaneously consuming a garbage barge of alcohol and drugs proved to be unsustainable. Contemplating suicide by the early '80s, he became a born-again Christian. He careened into a series of relationship events in which he would marry, divorce and remarry two women five different times. A reunion with son Eddy, who'd developed into a brash rocker during his dad's long absence, sparked their revelatory run of '90s albums. But a year after Eddy's mom died of cancer in 1999, the young guitarist suffered a fatal heroin overdose. Billy Joe had a heart attack onstage in 2001; and in 2007, he shot a man in the face after a barroom dispute (a jury acquitted him). Through it all, he plied his trade, hand-tooling parables, laments, boasts, warnings and praise songs in his own hardtack, scriptural idiom.

In 2010, loyal compadre Willie Nelson proclaimed Shaver our "greatest living songwriter."

As pillars of the outlaw-country movement (and its 21st-century rebranding as Americana), Jerry Jeff Walker and Billy Joe Shaver were remarkably complementary characters. The former was an idea man and networker (i.e., partycrasher), strutting and face-planting from pickin' session to guitar pull to dive bar to free-range DIY recording session to sprawling, rally-the-troops headline show (if stars, planets and whiskey aligned). The duende popped by to sprinkle crushed cypress leaves in Jerry Jeff's tub of Sangria on occasion. But the trickster spirit treated Shaver like a co-conspirator and primary vessel.

Lorca: "The magic power of a poem consists in it always being filled with duende, in its baptizing all who gaze at it with dark water... and this struggle for expression and the communication of that expression in poetry sometimes acquires a fatal character." Shaver, from his song "Good Christian Soldier": "And it hurts to have to watch a grown man cry / But we're playin' cards, writin' home, havin' lots of fun / Turning on and learning how to die." In other words, no matter the circumstances, you fight for your art with the passion of the possessed every day, until the duende is flowing in your veins.

That kind of passion takes a toll, but it's why Jerry Jeff and Billy Joe inspired so many artists in so many ways. The recording industry may have viewed them as volatile, unsafe bets who self-sabotaged and failed to maximize their commercial appeal. But fans and peers who actually cared about them were in awe of how the two men maintained the integrity of their music and careers with uncompromising, unceasing certainty. They shared and distributed their art widely, while repeatedly denying the bagmen from the corporate charnel house, whose only job was to micromanage their bosses' investments.

They didn't prioritize people who didn't prioritize the music. Jerry Jeff performed for presidents, but he treated the White House as the next line on his itinerary, another fluid situation. When Jimmy Carter, the "Rock & Roll President," kept him waiting without a word for two hours, he simply bounced, musing that he wouldn't be meeting the president since he heard the Commander-in-Chief didn't hang out in bars.

Or, as the chorus of another song from his debut album clearly states, "I make money, money don't make me."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.