Caption

Arthur Blank enjoys one of his favorite hobbies at Mountain Sky Guest Ranch, one of three guest ranches owned by Blank Family of Businesses.

Credit: Morgan Lee Pearson, courtesy of AMBSE Creative

Arthur Blank enjoys one of his favorite hobbies at Mountain Sky Guest Ranch, one of three guest ranches owned by Blank Family of Businesses.

Arthur Blank is worried that capitalism is getting a bad rap.

The system has worked well for the multi-billionaire and co-founder of The Home Depot. Now 78, he is largely beloved in Georgia as an entrepreneur, owner of two professional sports teams and a prolific philanthropist. But Blank regularly speaks on business school campuses, where future leaders and executives tell him they are anxious about the environment, the wealth gap, racial and gender inequities, and a litany of examples of corporate malfeasance. He notes pervasive cynicism about corporate leaders and perceptions that the drive for profit comes at the expense of public good.

In his new book, Good Company, Blank follows his own success to show that purpose and profit can — and should — coexist. The book lays out a set of values that guided him to turn around the struggling Atlanta Falcons NFL team, launch the Atlanta United FC soccer club and build the Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta.

Among Blank’s diverse interests are the nationwide PGA Tour Superstore chain, three guest ranches in Montana, and a family foundation that counts millions in economic development investments on Atlanta’s beleaguered Westside among its $660-million outlay to date.

Good Company is billed as a “visionary road-map” for creating successful businesses. It’s also part memoir of how his ethics evolved from watching his father run a neighborhood pharmacy in Queens, New York, to launching multi-billion dollar ventures. Like all stories meant to inspire, he takes some knocks. Blank writes about being teased for having a stutter. He shares how he and Bernie Marcus were brusquely fired from executive positions at Handy Dan Home Improvement Stores — the humiliating inflection point that led the pair to create The Home Depot.

That origin story is well known in business and retail circles as an example of how bold, disruptive thinking can change the game, but Good Company provides a more personal view. There’s a revelation of Blank stumbling dazedly into a parking lot after being abruptly forced out of Home Depot in 2001, and his devastation after the Falcon’s epic 2017 loss in the Super Bowl. He details the inception and rapid success of Atlanta United, and responding to the NFL protests that began in 2016. He also goes public about the pain of learning of Michael Vick’s role in an illegal dogfighting ring, along with other ups and downs in a life of unimaginable financial success.

GPB’s Virginia Prescott asked Blank about some of those stories in a conversation presented in collaboration with Marcus Jewish Community Center of Atlanta’s “Book Festival in Your Living Room”, the National JCC Literary Consortium and the Atlanta History Center.

Arthur Blank’s brother, Michael, and his father, Max, are photographed outside the OES Pharmacy family business, in 1940. Max died when Arthur was 15, leaving his mother to grow what became a multi-million-dollar business.

We were living in a single-bedroom apartment in Queens. And it was early on a Sunday morning. And, you know, living in poverty, we had friends coming by all the time and what have you. And somebody knocked on the door. My dad didn't look at who it was. He just opened the door. And next thing I know, he was sitting on his knees and with a gun to his head. And there are two [robbers] and they want to know, "Where's the money, where's the cash?" They put my mother, my brother and I in the living room with one of them and the other was searching the house, looking for cash that wasn't there. I still remember this as if it was yesterday. He had a gun on his lap, sitting on his right thigh. And my mother was giving him a lecture saying, “You realize this is not what your parents would want you to do. This is not a good way to make a living. You need to figure out something else to do for the rest of your life.” And after a while, he said, “Would you please shut up?” And she never did.

One of the robbers tied me up in the bathroom, the bathtub, and I said a few things to him, which, at 10 years old, I don't think my mother even knew I knew those words. And I remember him looking at me saying, “If I told your mother what you just said, she would wash your mouth out with soap.” But that was the last thing I said. I was gagged. But that was typical of my mother. She was a woman of great principle, great personal authority. And in fact, one of her famous expressions was: “You do the right things for the right reasons and live with the consequences of them.” And I'm trying to build that into my life as well.

[That’s] something that I talk about in the book, which most people are not aware of. I have what's called a veil state, or I am a stutterer. I'll flip words around, you know, subconsciously and, and make sentences complete. I went to a small business school outside of Boston called Babson College … I would always sit in the front because I always wanted to pay attention and learn. Then I would not be bashful about asking questions. But my mother would say to me, “You know, what you have to say is important. So you take your time, you get the words out and people will listen to you.” So I think that from those days in college where I raised my hand and I know my buddies around the class would think, “Oh, boy, here goes another 5-minute answer,” you know? But I would keep raising my hand. So it really never defined me. I mean, I was stuttering when I was senior class president, [and in] student government.

Home Depot co-founders pictured in 1979, a year after the first store opened. Left to right: Dennis Ross, Arthur Blank, Bernie Marcus, Pat Farrah, Ron Brill.

The firing in 1978 was a political situation primarily between my partner Bernie [Marcus] and a gentleman, that has passed away now, who was his boss. So, we had great confidence in our own abilities. We had the option of going to a variety of companies, doing a variety of things in a traditional sense of management leadership. But we both said, you know, if we ever had to compete with Handy Dan — that was the most successful conventional chain of home improvement center stores in the country at that time — it would be with a large, no frills, downmarket store. But, we really could not have done it without great service, great pricing, and great product knowledge. So, then we opened up The Home Depot. That was in 1979. And today that's 2,200 stores in Canada, United States and Mexico probably have a market capitalization today of about $300 billion. So, I would say it was very successful.

When I left [Home Depot] in 2001, [it] was the second largest retailer in the world, second only to Wal-Mart. So it was a great story and is a great story. There was a six-year period in there, when things went a little south. We had a different leader [Robert Nardelli ] in place that was eventually replaced. But the two subsequent CEOs — the gentleman there today, Craig Minear, the CEO and president Ted Decker — both live the culture. If you go to a Home Depot shareholders meeting, they start out every single meeting for 42 years now with this value wheel that we developed. It's an inverted pyramid that speaks to our whole orientation and all of our businesses today. And at the top of that is who is being served comes first. The guest. It's the fans. It's the customers. Those come first. Our frontline associates and all those businesses come next. And myself, if you will, I'm at the very bottom of the pyramid as a servant leader and somebody who is there to provide leadership, but also provide whatever that needs to be done for us to be successful. And it's all connected not only to associates, but to the communities in which we live and operate. I've always believed that the circumstances around me might change, but these core values, which we discuss in the book, they're not mine, they really belong to all of us.

I know you see my partner, Bernie, on Fox News very often. I listen to what he says and sometimes I'll cringe. And I love him. He’s a combination of father and brother to me. I do know it is hard. Bernie has great values and Bernie cares deeply not only about our faith, but about giving back. His percentage of giving back from his estate will be equal to mine ... and some of his philosophies don't exactly match mine.

I know you see my partner, Bernie, on Fox News very often. I listen to what he says and sometimes I'll cringe. And I love him.

But I know that his essence, at his heart and his soul, is a really good person that cares deeply about humanity. And I know he considers the blessings that we had coming from Home Depot [and what it’s done] for all of our philanthropy today and all of our businesses today to be something that we're very thankful for. So I would just cut him some slack. He would say, “I don't need to be cut any slack,” you know. But I know where his heart is and his heart is really in a good place.

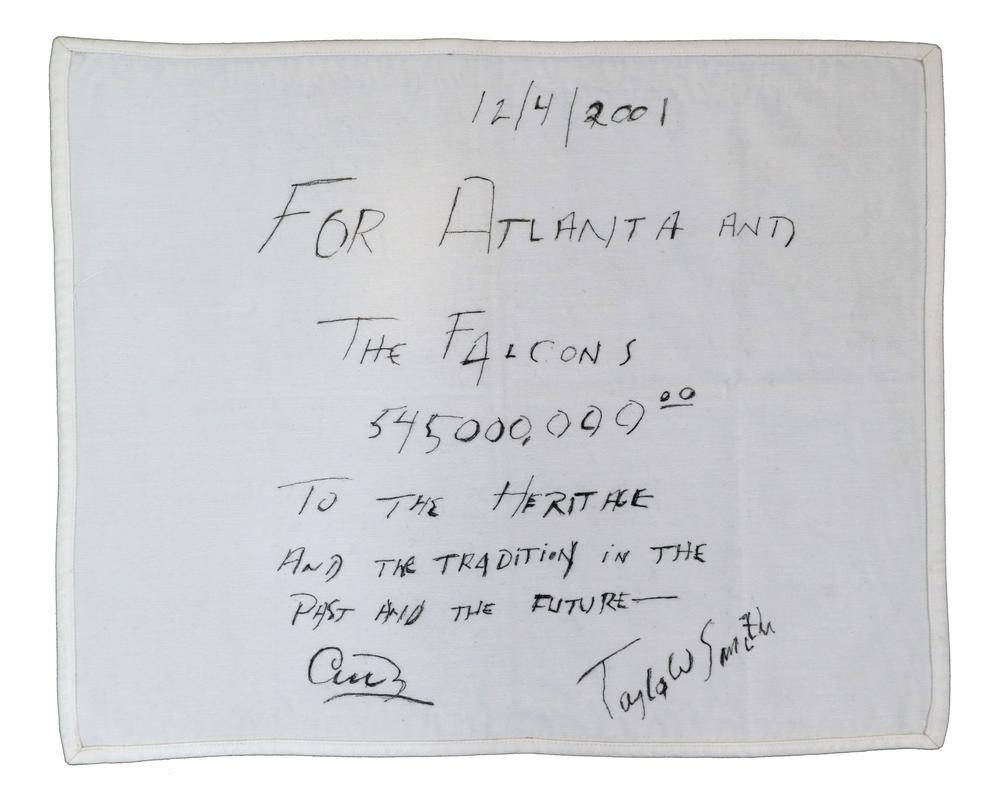

Pictured is the famous “napkin deal” that sealed Arthur Blank’s agreement with Taylor Smith to purchase the Atlanta Falcons for $545 million in 2001.

I would suggest, for anybody in business, that you listen to who you're serving. In our case, the fans, customers, guests or grantees, whatever the case may be, you're going to find out the ultimate truth of what you need to do to build a business response to issues, spot opportunities, deal with problems, whatever it may be. So in this case, we were coming back from a game after the team had played in St. Louis against the old St. Louis Rams — they’re now in L.A. — and instead of riding in the front of the plane with the coaches and managers, I sat in the back with the players. I said, “Look, I'm going to be a new owner, tell me what I can do to help. … I mean, you know, all those things. But tell me what I can do to help?” And they said, “Well, you know, the reality is about 40% of our stadium is empty. Of the other 60% who do come, half are rooting for the other team.” So I understood what they were saying: They just wanted support noise. They want to have a home-field advantage. So we spent six months maybe talking to fans, or people that were not fans, but were, you know, living in the Atlanta area at that time, and we found out that there were four or five things we had to fix. One was in pricing. Ticket pricing was higher than it could have been or should have been at that time, and so I brought Dick Sullivan over from Home Depot, the gentleman who now runs our PGA Superstores and we came up with a strategy that we've got to sell season's tickets for $100. So that was a low price … a lower price than before Michael Vick — the star quarterback — was born 22 years before that.

I remember I called the commissioner then, who was Paul Tagliabue, and I say, “Well, Paul, I have this idea. We don't have any fans in our building, and this is what we plan on doing: We're going to, you know, promote season tickets for 100 bucks or $10 a ticket.” And I remember waiting for, you know, probably two minutes. And if I stop talking now for two minutes, you realize just how long two minutes is. So there wasn't a word on the other end of the phone. And I think we got disconnected. I said, “Paul? Paul, are you there? Paul, are you OK?” I was going to call his secretary, thinking Paul got a heart attack or something. But he was there and he finally said, “Listen, you own the franchise, you have the option. You can do whatever you choose to do. You're going to get a lot of your fellow owners really pissed. But go ahead and do it, if that's what you want.” So we did it.

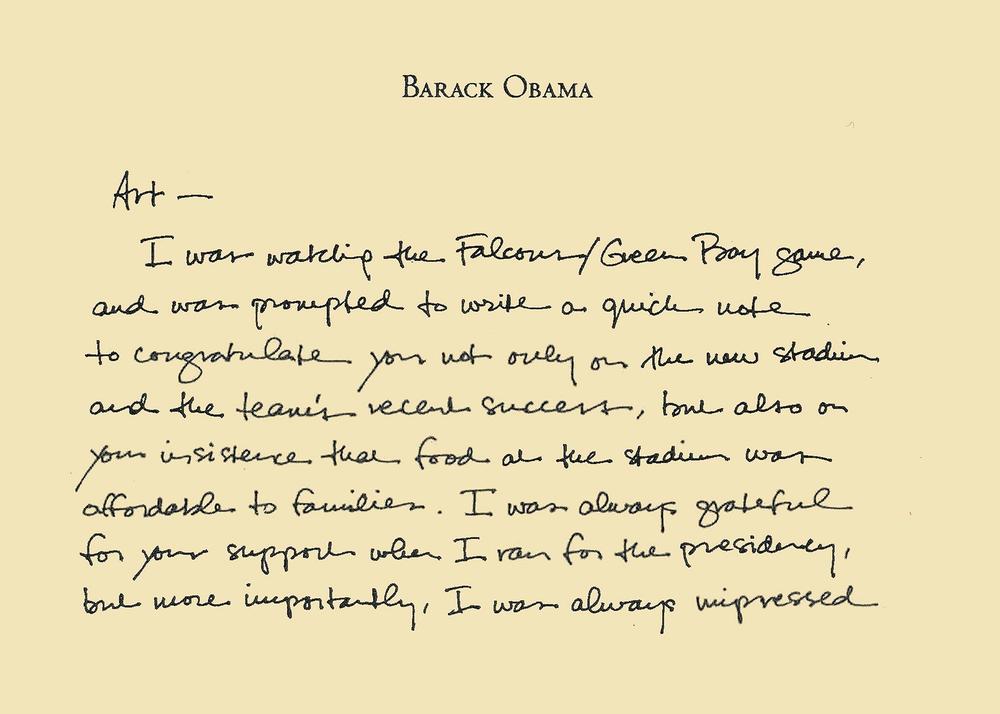

A message sent to Arthur Blank from President Obama in 2018, thanking him for his commitment to affordability at the Mercedes-Benz Stadium after Blank cut concession prices by 50%.

We sold out the entire stadium in two-and-a-half hours. All those 25,000 tickets were gone. And so from there, since the 2001- 2002 season, we've only had three games that were not sold out during the season. And that’s despite our recent record, which hasn't been, you know, one I'm particularly proud of, but we'll get better. But in any event, that was part of just being a good listener. And being a good listener, it's an art form … that we all can possess. All of us as human beings, I think need to do a much better job of being a good listener. We’re usually very happy to talk, very happy to share our opinions and what have you … I have enough humility to understand that the people we’re serving know better.

All the issues that Colin [Kaepernick] raised at that time [2016-2107] about the social injustice and lack of equality and equity in the criminal system and all those issues, I think they were real then and they're certainly real now. I think when the president [Donald Trump] in the fall of 2017 commented during his speech in Alabama about — I don't want to use the words, you know what they were — but he termed the players that were kneeling, in my view, in a very derogatory way.

So we had 35, 40 players kneeling before that, after that speech, we had close to 300 players kneeling because they took it personally and their families took it personally and their parents and their siblings and their grandparents and their heritage was being challenged. Seventy percent of the players in the NFL are African American — a disproportionate number. Their siblings, their families, you know, may have gone to battle and wore a variety of uniforms for our country over many, many years. So there was no disrespect to the military. They were trying to indicate that what the military had fought for — these rights, the civil rights, the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, etc. — that those rights were not being fully reflected in our society today. So that's really what it was about. And whether, you know, be it Dr. King or, a great friend to America and a great leader, Congressman Lewis, [who] was a great personal friend of mine and served our country beautifully, would say peaceful nonviolent protest is how we that's how we make progress. And Ambassador Young, another good friend would say the same thing.

Now, there's no place for violent protest. There's no place for looting and stealing and whatever else. That should never be tolerated. However, peaceful protests really go back and look at the history of our country back to the Boston Tea Party. I mean, people were throwing tea off those boats because they were protesting, you know.

Both John Lewis — John, just a month before he passed away — and Andy Young have said to me that we do have to recognize that things are better than they used to be. You know, better than in the ’40s and ’50s, but not where we should be. We need to recognize those truths. And if you go to the Museum of Equal Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, [Equal Justice Initiative Director] Bryan Stevenson says the same thing: We need to recognize [that] these 5000 lynchings took place in the United States [a 2019 Report from the EJI documents more than 4440 racial terror lynchings in the U.S. between 1877 and 1950]. And we need to figure out, you know, how do we move past that and how do we learn from that and how do we get connected with our current reality? So, long story short, I think, is that we should recognize the past, understand the progress we have made. And then as Dr. King wrote in his last book, which his wife published a year after he passed away. You know, he uses the phrase “community of chaos,” that we move away from chaos and towards community and community in a very broad sense, community with each other. Support more understanding and be better listeners trying to see how the other people, you know, try to stand in the footsteps of others.

Arthur Blank greets a crowd of cheering Atlanta United fans in 2017.

No. 1, I think at that time I didn't probably fully appreciate the environment, the communities and neighborhood that Michael was raised in, an area called New Newport News. I had another NFL player, while [Vick] was in prison, come visit me and say “I came from exactly the same neighborhood, but it was in a part of Pittsburgh.” So sadly, Michael was raised in an environment where that was kind of normal behavior, if you will. It's hard to believe. But he was.

I stayed in touch with him to some degree when he was in prison. When he came out, he was on house arrest and I took a meal to him and his family from his favorite restaurant here in Atlanta. And I remember he told me, he said, “You know, when [I went into] the prison system, they gave me three pair of underwear, three shirts, three pair slacks, three socks and one pair of shoes, and that was it.” He said, “That was all I was going to have,” as opposed to the lifestyle he was leading before. And he had to mop the floors for weeks and months on end. And then he worked in the laundry. He said, “All of that really gave me time not only for redemption, but more importantly, for reflection.” And he said, “I really realized that I had done a lot of good things in my life putting aside and playing ball. But, you know, I needed to change my view on what I could give back and how it could be connected to other people.”

He came out of the prison system as a changed person for the positive, not for the negative. Sadly, sometimes these young men and women get involved in that cycle and they never get out of it. But he did. His faith is very strong. He's committed to his wife now, his children. And so he's used that time since he got out of prison and giving back to community, speaking to young people. Not about dogfighting. But it's really not a story about dogfighting. It’s a story about making bad choices and the impact of young people. If you don't make good choices, you can end up being in really bad places. And so think about the implications of the choices you're making for yourself and for your loved ones, etc. And so he speaks to people throughout the United States, young people primarily, about that. He's done a lot of work in terms of animal rights, which has been great and been appreciated by all of those agencies and all those institutions. But really, in my view, it's mostly that talking to young people about, you know, here's somebody who's been there, done it, gotten on T-shirts, lived it, and somebody whose name they respect or the least they know of, I should say, in most cases. And so he carries a weight of authority that somebody who's just called a suit and comes in and talks to them and doesn't quite feel the same, same way. So I'm happy to see that, you know, he came back to Atlanta and spent time here.

Now, the last game we had in the Georgia Dome before we moved to Mercedes Benz Stadium in August of 2017, we were honoring all of our ring of honor members and he was one of them. And I told him before, “You get in a convertible and drive around the field and Michael, there are 73,000 people in the building. I'm not sure how they're going to receive you. They said it would take an act of courage on your part to go out on the field and and to be recognized.” And, you know, people stood up! Seventy-three thousand stood up and clapped, gave him a great hand. And then he came up to my suite afterward and it was like 10, 15 minutes later, his face was just full of tears and he said that he was so moved by it. And that's all part of his story of redemption and his story of being a changed person. So it was good.

So when we started, MLS was ranked like 22nd among all the leagues in the world. Now it's ranked like seventh. So, you know, soccer is on the ascent in the United States dramatically, which is a great thing. I felt and others felt that we could be successful here. So we designed our stadium to accommodate not just for the Atlanta Falcons and National Football League football — American football — but soccer as well. Soccer fans don't want to feel like they go into a stadium and they're a second-class citizen citizen. So everything is designed to accommodate the soccer fans so they feel like this is their place as a result of that. And we've had a very successful team for the first three–and-a-half years this year. A little shaky now. Hopefully we'll get back in the playoffs, but not as well as the first three years. We've broken every season ticket record per game. Playoffs, playoff championships, etc. We hold all the records. One of the beauties is that when you come to the stadium, it feels like it's the United Nations. I mean, it doesn't make a difference how old you are. Young you are. I mean, everybody's standing for an hour-and-a-half and they just don't sit down. I mean, those fans, they feel like that's the only sport that we're hosting in that stadium. And they love that. And they love the camaraderie. And, you know, you see the blending of every type of person and personality you can imagine. It's a beautiful thing. And that's an example of the happiness that we're talking about.

It starts with respect. I've had conversations with a number of senators who made it very clear that some of their best friends, both politically and otherwise, are on the other side of the aisle. And they've worked collectively for the United States, for everybody in this country, 330 million people. So I think that part of that comes out of really being a good listener and responding to what you're hearing and trying to find a way to make things work for the benefit of everybody collaboratively. And that's it. You know, dig in [your] heels and it becomes, "My territory, your territory," etc. So, I think the great political leaders and the great spiritual leaders, in my view, have always, always opened up their arms and included everybody. And that's one of our core values as well: Include everybody.

I think back when I lived in a neighborhood, you know, a small neighborhood, when my mother and dad were alive, we all took care of each other. I mean, it wasn't like, “You're Republican or Democrat. Which country do you come from? Where did your parents come from with your grandparents?” We all came from someplace else, other than the other Native Americans. So, that represents that melting-pot philosophy: We’re all in this together. When you find common solutions that work for everybody and [are] respectful of everybody to represent the best of you. … So I would fight for that and surround myself with people who believe the same thing, because you have to have that brain power in every institution or corporation or nonprofit. At the end of the day, you can have differences of opinion, which is a great thing to have, and different approaches, which is a great thing to have. But you want your core values to be the same, ideally. And the core values that our forefathers drafted for us — they weren't perfect, either, but in their own ways, they strove for those things. … These are the kinds of people we need in leadership today, not thinking about red, blue, purple. Think about “How do I listen to the people that are actually trying to serve and how do we put results in place that would give them the very best chance for equality and for success and for fair treatment?” And I think we have to strive more for that.

No, I'm not. ...Well, I shouldn't say I'm not. I am, in a certain sense. I mean, you write a book like this, it's really getting into kind of the political arena. It's not trying influence, but trying to share philosophies of life and stories and thoughts about a certain set of values, which really transcend business, nonprofit, as well as the political arena. So the answer would be yes. In that way, I don't think my personality, probably, or my patience level probably is not the level it would have to be to sustain myself in this political atmosphere today.

... my patience level probably is not the level it would have to be to sustain myself in this political atmosphere today.

But, you know, I think the word “civility” is terribly important today in the political world in which we just don't see it the way we need to see it. And the great political leaders in the past, they were civil and they were good listeners. And they found ways to get things done with people who had a little bit a different view but found that commonality that was really important.

I look at my six children, Batch 1, Batch 2, and, you know, they go from age 19 to age 52, if I have it right. They all have a great set of eyes and they're all different. They all have a great set of values. They all live life with purpose. They all understand it's, you know, you have an opportunity to be here on Earth and how do you want to leave it? Tikkun Olam [a Jewish concept of repairing the world through action]. How do you help repair the world if we can use that expression? How do I do my part in it? And how do I put my shoulder to the wheel and lead by example and take the blessings of all the resources that our family. As I've said, 95% of my estate is going to be recycled back through our foundations and they will provide their insights and their leadership and their views and values that their father and their mothers would be very proud of.

_______________________

GPB intern Eva Rothenberg contributed to this article. Proceeds from sales of Good Company go to the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta. Also watch RISING UP: A Westside Story, a documentary film by David Lewis Productions that gives viewers a detailed look into the ideation, construction, and impact of the Mercedes-Benz Stadium on the city of Atlanta. The documentary will premiere exclusively Nov. 23, 2020 at 8 p.m. on Georgia Public Broadcasting.