Section Branding

Header Content

'Song Of The Avatars' Resurrects Guitarist Robbie Basho's Lost Recordings

Primary Content

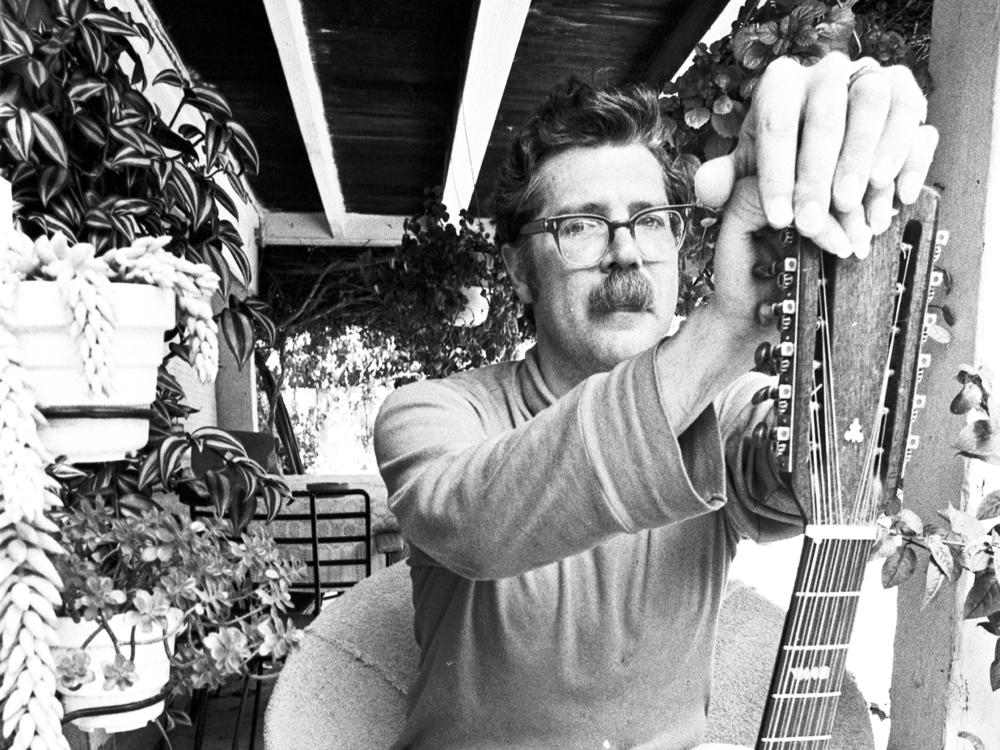

A few years ago, filmmaker Liam Barker was at work on the film that would become his 2015 documentary Voice of the Eagle: The Enigma of Robbie Basho. Barker's subject was the late guitarist who (along with figures like John Fahey and Leo Kottke) helped invent the acoustic style known as American primitive, and he kept hearing about a collection of the artist's personal recordings that had seemingly been lost after his death in 1986. That's how the director found himself in a ramshackle house in South Carolina, surrounded by stacks of old newspaper and animal excrement.

"When I went there, it was kind of like something out of a horror film," Barker says. "It was like, you know, unbelievable filth all around."

But to his amazement, Barker found exactly what he was looking for: box after box of magnetic reel-to-reel tapes, still sealed. "Miraculously, some of these recordings sound like they were recorded yesterday," he says.

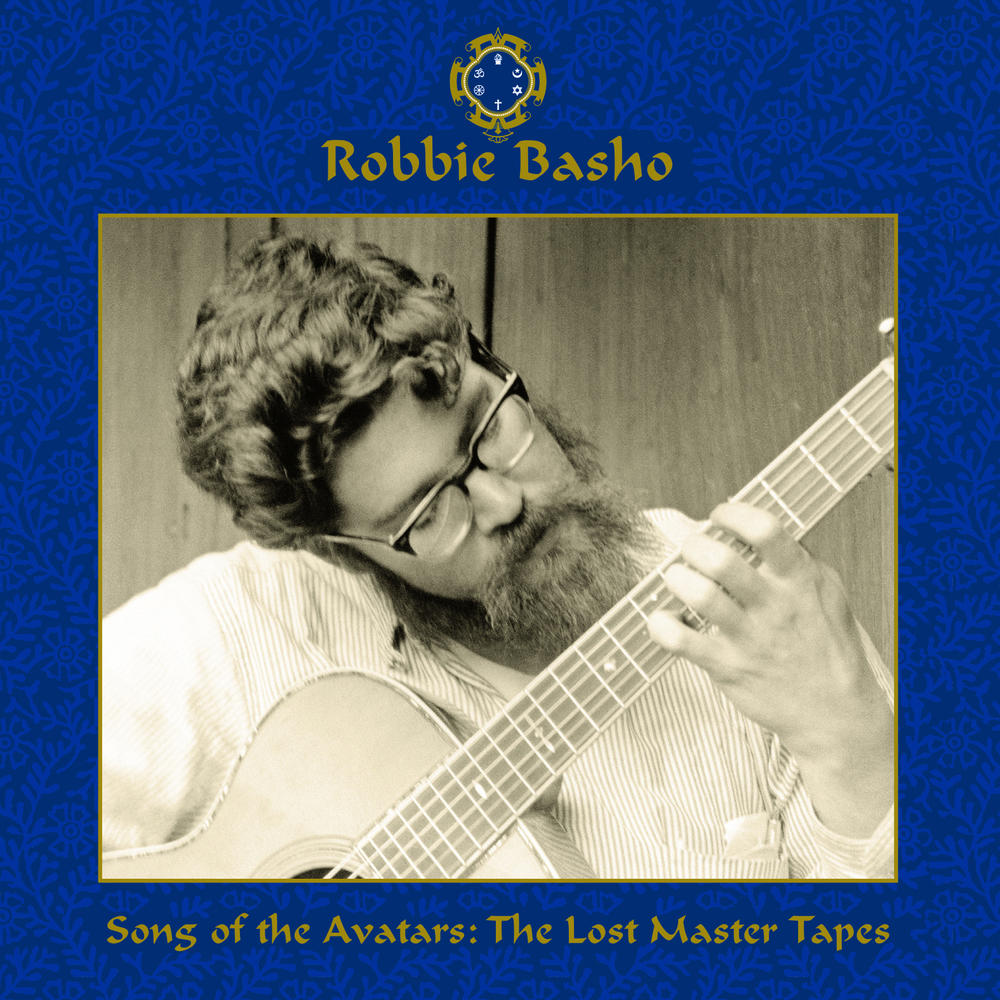

Now, the personal recordings stashed in those boxes are being released for the first time in a five-disc set called Song of the Avatars: The Lost Master Tapes.

Basho's music never found a wide audience in his lifetime, but it's had a deep impact on generations of fellow guitar players and listeners — including Pete Townshend, guitarist and co-founder of The Who. "I think anybody, any young guitar player that hears his music today, would be influenced by him," Townsend said in an interview in Voice of the Eagle. "It's beautiful and eloquent and profound, and full of love and devotion and melancholy."

Basho had his own way of describing his work. "I don't call a lot of my stuff 'far out' — I just call it a different level of feeling," he said in a 1974 interview with Pacifica radio station KPFA. "I spent years on the road singing folk songs that had no meaning, you know, just emoting these things. And it got dawned on me, music is supposed to say something. Music is supposed to do something. Then I started trying to see how high and beautiful I could go."

An adopted child, Basho grew up in Baltimore as Daniel Robinson. He started playing the guitar as a student at the University of Maryland in the late '50s and early '60s, when he befriended fellow guitarists John Fahey and Max Ochs.

"When I started out, there was a big cult in D.C., in the University of Maryland, of country blues," Basho told KFPA. "It was kind of the only vitality around. The music of those days was so artificial, you know, that we couldn't believe it. ... I was doing that, and thought I was doing something. And then I heard Hindu music."

Basho moved to Berkeley, where he immersed himself in Eastern religion and music, and renamed himself after a 17th-century Japanese poet.

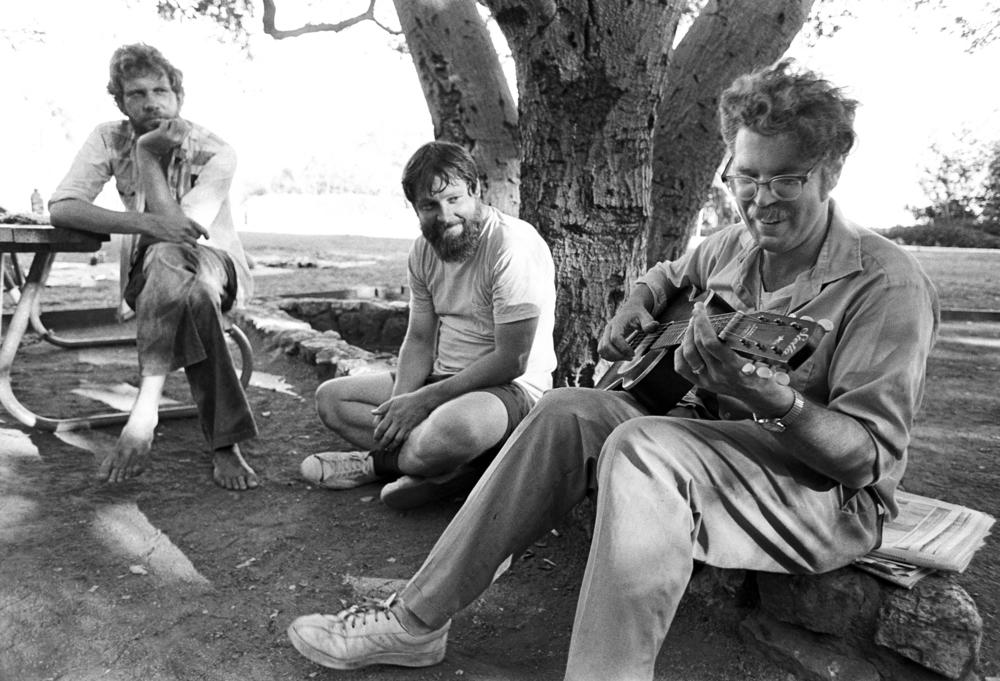

"He was genuine and unselfconscious about what he was doing," says Glenn Jones, a guitarist and collector who became friends with Basho in the late 1970s. Jones says the older guitarist invented his own style, drawing on musical influences from all over the world.

"There was nothing fake or put on about it," he says. "You listen to those records, and it doesn't sound at all Persian. It doesn't sound at all Indian. It doesn't sound at all classical. It just sounds like Robbie."

Basho's friends and family describe a guy who was deeply committed to his music, but was otherwise a loner, plagued by anxiety. "I always felt that there was more going on than he could really express," Margaret Lewis, a former girlfriend of Basho's, said in Voice of the Eagle. "I loved his music. I was convinced that he was going to be the next big thing, but that wasn't really his interest. His interest was in making the music, not in getting a lot of attention for it."

In the '70s, Basho became involved in a spiritual order called Sufism Reoriented, and his records came to feature more and more of his singing, in an earnest, full-throated style that provokes ambivalence even among his fans.

He was 45 years old when he died from a ruptured artery in his neck. All of his records were out of print at the time. He left most of his possessions to Sufism Reoriented, and they wound up scattered across the country, with his collection of recordings landing in that house in South Carolina. Glenn Jones says the rediscovery of these recordings is a major addition to his legacy.

"Some of the guitar solos just knock me out," Jones says. "Why did this never make it onto any of his records? It's as good as anything he released commercially. And here it has been, moldering in these cardboard boxes since the '80s."

The compositions on those tapes span Basho's entire career, from his earliest experiments with the blues to the sprawling compositions of his later years. But as he said in that 1974 interview, his goal stayed the same.

"Me and [Leo] Kottke and [John] Fahey ten years ago started taking the steel-string guitar and really trying to make it a concert instrument," Basho said. "You know, gut string is great for love music and so forth. But the steel, you can get fire. You can ride, and you can fly."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.