Caption

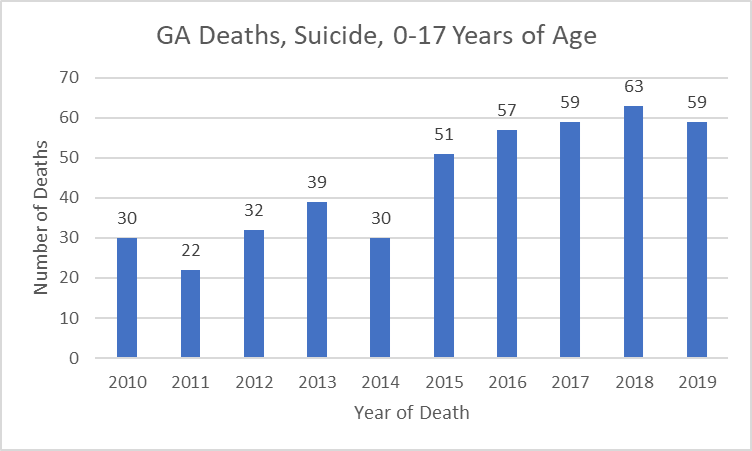

The pandemic brings with it evidence of increasing anxiety and depression in Georgians under the age of 18. But the latest preliminary data from the Georgia Bureau of Investigation show a significant drop in youth suicides through Dec. 4, 2020..

Credit: JESSICA TICOZZELLI / Pexels