Section Branding

Header Content

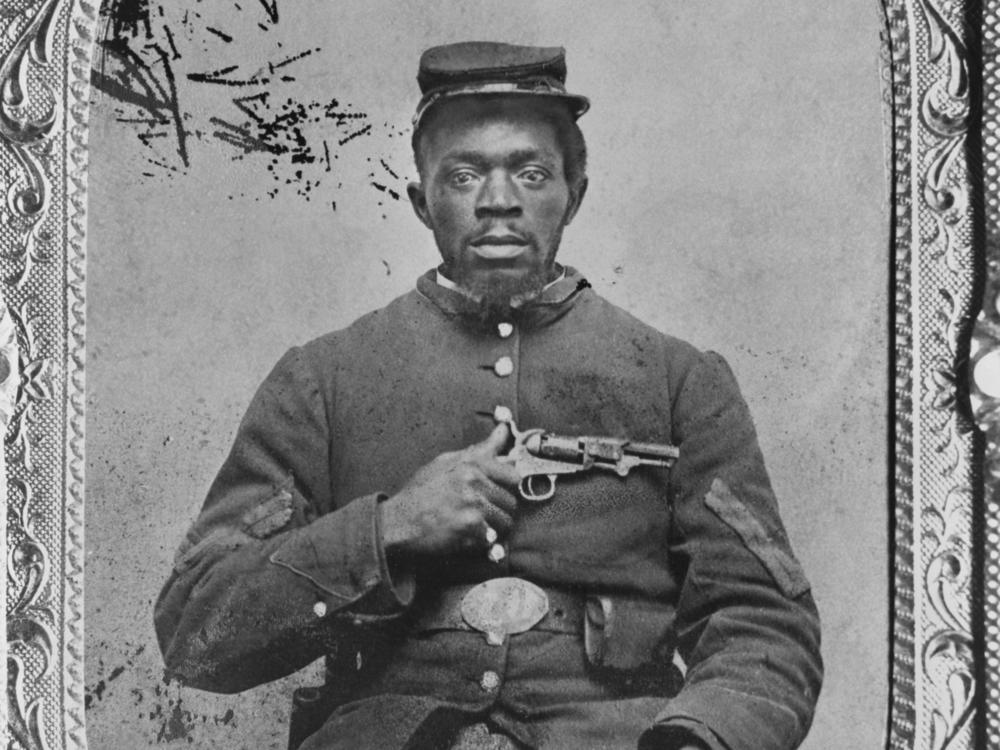

From Negro Militias To Black Armament

Primary Content

Guns are just about as American as apple pie. To many, especially white folks, they've represented all the highfalutin ideals enshrined in the constitution: independence, self-reliance and the ability to live freely. For Black folks, guns often symbolize all those same things—but, as we like to say on the show, it's complicated.

As we talked about on our latest episode of the pod, firearms have always loomed large in Black people's lives — going all the way back to the days of colonial slavery. Right from the jump, guns were tied up in America's thorny relationship with race; you can actually tell the story of how America's racial order takes shape, in part, by tracing the history of guns in the U.S. and who was allowed to own them.

To try to understand that (very long) history of race and guns and make it digestible, we talked to Alain Stephens, a reporter with The Trace who has been reading about the history of Black gun ownership for a long while. Here's the extended cut of our conversation, which has been edited and condensed for clarity. And we also asked Stephens to recommend some of the books he read for his research, which you can find here.

Guns and Black people have both been in this country for centuries now. How did firearms factor into the earliest days of the United States, particularly the institution of slavery?

I think the first thing that we need to do is go all the way back to the introduction of the firearm into Africa, because I think that's a very important thing as far as how it influences the slave trade. So once upon a time in Europe, there are a series of wars, and this essentially builds up a lot of firearms technology within the continent of Europe. But for the most part, in the 16th and 17th century, these firearms stayed on the European continent. This is for two main reasons: The first is that, at the time, the Catholic Church prohibited the sale of firearms en masse to non-Catholics. The second is there's a technological barrier; firearms at the time didn't operate particularly well in tropical climates, and the ignition systems were just not very reliable.

This all changed with the Protestant Reformation. Protestant slavers go into Africa, and the weapon that they're bringing is now this new and improved flintlock musket, which can operate better in tropical climates. It's a lot cheaper, a lot more reliable and it's easier to fire. And this in turns becomes the currency in which these Protestant slavers used to purchase the first slaves, to even get that first leg of the triangle slave trade up and running. You can actually see this in records; there's a direct correlation between the increase of gunpowder imports into the African continent, going along with the increase in slave exports leaving the continent.

And I think that's a very important kind of measure. Because for many white Americans, the introduction of the firearm is this one of self-determination and independence. For Black people, the introduction of the firearm can mean all those same things that it does for white people. But at the very same time, it is the actual currency and technological implement used for their bondage.

We know that the colonies there granted rights almost exclusively to white male landowners. So what kind of rules in the early colonial period governed the way people owned firearms?

There's this notion that the first colonists essentially jumped off the boat and they were all armed with muskets. But that wasn't the case. Going back to England, firearms were something mostly reserved for the military, royalty and aristocracy. And this kind of rubbed a lot of common folk the wrong way. That changed by the time they got to the first colonies. The British crown, however, was quite apprehensive about giving a bunch of far-flung white colonists firearms. But the white colonists had three major security threats that very much kind of sent them into this existential crisis, which would call them to have firearms. The first one was the Indigenous threat from Native peoples. The second were these internalized threats, from white indentured servants. And [third], there was the larger threat from having Black slaves. And so for these three reasons, the early colonists would actually have to appeal to the crown to get firearms.

The state actually did have to step in and arm the first colonists. And then, there were the first gun control laws. They were racialized gun control laws, and they would also mandated how early colonists interacted with firearms. And that was not very independent; it was very much controlled. There were armories and store housekeepers, and they would check your weapons out and bring them back. And if you fired a weapon or if you had lost a weapon, sometimes it was punishable by death.

So you mentioned the Indigenous threat. Can you talk a little bit about that?

There were competing colonial interests. The British crown tried to limit the sales of firearms to Native peoples. But even when they did so, the Spanish and French would go behind their backs to arm them for a variety of different reasons. So it was very hard to institute any sort of universal gun control with Native peoples. Now, it doesn't mean that they didn't implement some sort of controls; one of the means colonists would kind of mitigate Native peoples' firearms capacities would be by essentially forcing all them to make their repairs at the same place. There have been accounts where white colonists would be battling with Indigenous people, and they would simply stop repairing [Natives'] firearms and wait until they [broke]. Then, they would come in and essentially finish the skirmish. That's how they would fight their wars.

So you talk about the ways that guns were used as literal currency. But guns played a really important role in some of the pivotal moments in US history, in which racial caste becomes codified because of rebellion. So tell us a little bit about how guns factored into those early uprisings, like Bacon's rebellion and Stono's Rebellion.

Throughout U.S. [and colonial] history, there are about 270 slave rebellions. And the U.S. government was particularly and acutely concerned about this, because there had been a precedent for a successful one: the Haitian rebellion, which essentially kicked out the planter class. Rebellions were something that many white Southerners, as well as the U.S. government, had used as kind of a rallying cry to ensure that the apparatus of slavery was secure.

All the way back in 1676, we had Bacon's Rebellion, which occured in Virginia. It was a particularly interesting rebellion, because it was an allyship between Black slaves and white indentured servants; essentially they took a bunch of firearms and they tore stuff up. And the government's response to that was to roll out slave laws. And part of those slave laws were meant to ensure that Black people, whether they were enslaved or free, were not able to get firearms. You see throughout time and time again throughout history. These rebellions would occur, and the government would step down hard and fast to further racially stratify the laws.

My favorite story, though, is Stono's Rebellion. It occurred in South Carolina in 1739, and it was actually a direct reaction to a gun law. The white planter class had begun to get acutely aware of the fact that Black slaves were beginning to outnumber them. So in an effort to mitigate a potential rebellion on the colony, they passed the 1739 Security Act, which would mandate that the white planter class males would carry muskets to church with them on Sunday. And the rationale behind that was that, on Sunday, slaves were given their most free time. And because of that, the white planter class believed that slaves were most likely to launch a rebellion at that time. So they passed the Security Act, and right before it was to go into effect, a bunch of slaves revolted on a Sunday, when they knew their masters were unarmed. They ran into a storehouse, killed the owner, took a bunch of guns, and started marching down the street. They killed more of the white planter class, and they kept on recruiting more slaves from plantations. Unfortunately for them, they were [eventually] caught by a posse and killed, but this sent a kind of shockwave throughout white planter class at the time, about the security threat Black slaves could pose.

And things only got worse and more violent as we moved forward towards the Civil War, right?

In the 1850s, there was the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, which allowed slave patrollers to pass onto free state territory and bring back human property to the south. This caused a bunch of different problems. A lot of Black people had fled to these Northern states and had started to create a new life. Now suddenly, they're fugitives and back on the lam. The second thing is the documentation [around slavery] back then was so poor that there was a legitimate concern that free Black people in the North could simply be kidnapped and taken back to the South where they were put into slavery.

So what you actually see here is this entire self-defense armament movement that restarts back up with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act. In the 1850 October edition of the abolitionist paper, The Liberator, they say how Black people and abolitionist whites had flooded to gun stores to start purchasing revolvers [in response to the act] and how white accomplices and allies were actually donating firearms to their Black compatriots for self-defense. There is this rich history of fighting that goes up to and throughout the Civil War, where Black people [are doing what is necessary] to simply survive.

Fast forward to the Civil War, during which Black people served in the U.S. army for the first time—and were armed. Once the fighting stopped, you had a trained and, in many cases, recently emancipated Black populace. What was the relationship between Black people and guns after the war?

This is the part that is really the most unsung part of Black armament in American history. Right up until the Civil War, [Black gun ownership] was essentially illegal activity. There were so many laws that mandated that Black people couldn't have firearms — a Black person owning a gun was a sheer act of defiance. So when the Civil War ended, the Union government did not exactly know what to do. They knew that they wanted to end the system of slavery, but past that, there were a whole array of ideas that white people in America had about how to handle Black people. But for Black people, the fundamental thing was: I'm free now. How can I maintain that? It was a very different thing to go to a free Black person at that point and tell them that they did not have the right for self-defense; it accompanies the very notion of freedom. So for the very first time, we have Black people who are for the most part free to go about and acquire weapons.

The end of the Civil War essentially created a post-war environment, filled with power vacuums and filled with a lot of former military officials from both sides of the war. There were huge security threats everywhere, and there were a ton of guns. Because there was no law and order, the federal government actually passed a law allowing the rearmament of militias strictly to go out and enforce essentially kind of like law and order. The problem was that these militias were primarily white. They would harass Black people and disarm them. The federal government actually would jump in and ban these white militias for for a short period of time.

Eventually, the federal government reversed course. It allowed militias to reassemble, and the militias that formed were actually be Negro militias. In states like Texas, Arkansas and South Carolina, you would have these radical Republicans being threatened by Southern Democrats who were conducting insurgent activities. So to combat that, they would raise these Negro militias, who would essentially fight this underground war against white supremacists throughout the country. In 1860s Arkansas, for instance, a radical Republican governor was part of an assassination attempt, and a congressman was actually assassinated by white supremacist insurgents. So the governor raised a [mostly] Black militia that combed Arkansas for four months and essentially eradicated the Ku Klux Klan there.

Fast-forwarding again, this time to the civil rights movement: So much of the mythology around it is, probably not accidentally, tethered to this idea of nonviolence. But there were guns all over the movement. So can you talk a little bit about the relationship that the civil rights establishment had to firearms?

As we move into the civil rights era, there's this nuance: For African American gun owners, the firearm is seen as this tool for charting one's own course and self defense. At the very same time, it is also that this lethal implement that could very much be turned against you—and throughout history, has been turned against you. This very much showed up during the civil rights era of the 1960s.

The first thing we need to know is that the idea of nonviolence was one that had formed and shifted over the years. Right. Even Martin Luther King Jr. himself had started off with indications of being more friendly to that notion of Black armed self-defense in the beginning of his movement, compared to the later half of his movement. At the same time, firearms had always been part of the movement, even when we talk about nonviolence. A lot of the coordinators, for instance, like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, had an uphill battle trying to convince Black southerners to not bring guns to protests.

The other thing is that this history of Black armament [in the civil rights movement] has always secretly been there. Medgar Evers, a very prominent civil rights activist in Mississippi, carried guns on him all the time. He had a rifle and a pistol in his car the day that he was assassinated in front of his home. And then you look at other ones, such as Fannie Lou Hamer, who was a civil rights activist, who famously registered thousands Black people to vote. And she did this in the South, right? She did this in one of the most costly and toxic places for Black people to even organize a political movement. She would tell everyone: You don't want to hurt anyone. You don't want to hurt white people. Right. But when push came to shove, she did say that part of her success was predicated on the notion that she kept the shotgun in every corner of her house. [Editor's note: To add a little more context to what Alain was saying there, Fannie Lou Hamer was talking about keeping a shotgun to protect herself from white supremacists in that quote. Having a shotgun in every corner wasn't a direct part of her political organizing; she had a shotgun to protect herself from white supremacists.] So, so well, there was very much a nonviolent movement. But there was still very much this defensive notion that, when the movement came home and as a Black person operating at home, there was this practicality of having a firearm there. And that practicality was one that Black people never quite divorced by simply just being in the realities of that violent environment in which they had to operate.

Alain's reading list:

-This Nonviolent Stuff'll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible by Charles E. Cobb Jr.

-Negroes and the Gun: The Black Tradition of Arms by Nicholas Johnson

-At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance—A New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power by Danielle L. McGuire

-1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back by David F. Krugler

-Negroes with Guns (paperback edition) by Robert F. Williams -Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms in America by Adam Winkler

-Too Great a Burden to Bear: The Struggle and Failure of the Freedmen's Bureau in Texas by Christopher B. Bean

- Policing the Second Amendment: Guns, Law Enforcement, and the Politics of Race by Jennifer Carlson

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.