Section Branding

Header Content

Objecting To Electoral Votes In Congress Recalls Bitter Moments In History

Primary Content

Many in Washington, D.C., are worried about civil unrest on Wednesday, as the Proud Boys, a group labeled as extremists by the FBI, and other activists gather to protest just as Congress begins to add its imprimatur to last month's Electoral College vote.

That congressional vote will be the final formality leading to the inauguration of President-elect Joe Biden two weeks later.

Whatever may happen in the streets Wednesday, it will not prevent Congress from performing its role under the Constitution. But it will likely heighten public awareness of that role and how it is performed.

And it may also heighten awareness of the role assigned to the vice president, who declares but does not determine the winner.

The formal processes of verifying and certifying the election results have gone forward on schedule since November, when Biden defeated President Trump. States certified their results, and the Electoral College affirmed Biden's win on Dec. 14.

But the final days of Trump's presidency have been fraught because he continues to deny the outcome and refuses to concede. Without evidence, he has insisted the vote had to have been rigged, manipulated or misreported. Just on Saturday, in a lengthy call, he urged Georgia's top election official to overturn the results in that state.

More than 60 lawsuits filed by Trump and his allies challenging the results in swing states have been unsuccessful.

Over the weekend, judges snuffed out a particularly quixotic bid by Republican Rep. Louie Gohmert of Texas and a group of Trump supporters from Arizona. In their lawsuit, they alleged that Vice President Pence has the power to accept or reject the Electoral College results from individual states.

News of Gohmert's suit, or its dismissal, may have been the first time many Americans realized that the vice president has any role at all at the end of the presidential election process. But the Constitution did create such a role, and it has been an uncomfortable one on numerous occasions.

A problem from the beginning

The writers of the Constitution decided to have the reported and sealed ballots from the electors (who meet and vote in their respective states) delivered to "the seat of government" and entrusted to the president of the Senate — who's also the vice president of the United States. The ballots remain sealed until the vice president opens them on the designated day and hands them to "tellers" to read out and tally.

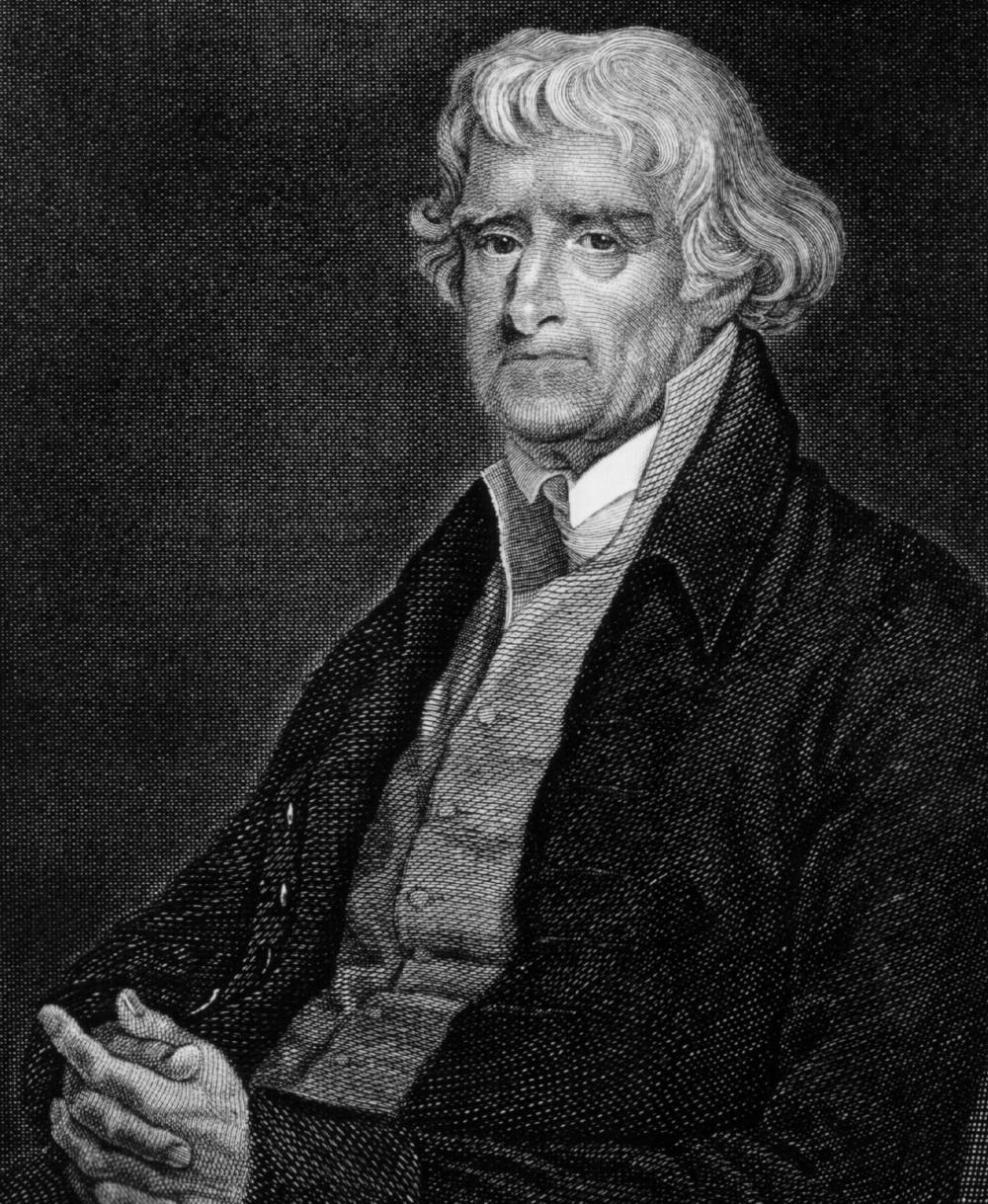

Since as far back as 1796, when John Adams was vice president, the job of declaring the winner of the presidential election has been at least potentially problematic. Because when Adams was opening the envelopes that year, the winner was himself. There had been some controversy over the paperwork from Vermont, but Adams' main rival, Thomas Jefferson, said he did not wish to make a fuss over the "form" of the vote when the "substance" was clear.

So Adams became president and Jefferson, as the runner-up, became vice president. (That was how it worked initially, until the 12th Amendment gave us something closer to the ticket system we have today.)

Four years later, the roles were reversed. Jefferson was vice president and was tasked with reading out the electors' ballots. This time there was a question about Georgia's vote, the reporting of which was technically flawed. Jefferson counted Georgia, and that meant Adams was no longer president.

Was the soon-to-be-president Jefferson out of line? There was no reason to think that Georgia had not voted for Jefferson, and the records show it in fact had done so. There was no competing slate of electors to consider. So excluding the report of Georgia's electors because of a technical error would have simply disenfranchised the voters of that state. In the moment, Jefferson had to make a judgment call, and he did so.

Deeper waters

The 12th Amendment tried to sort things out in 1804, but the Electoral College system soon got into trouble again, first in the disputed election of 1824 (when no one had a majority in the Electoral College) and again in the years before and after the Civil War.

After the election of 1876, disputes arose in several Southern states with two sets of electors claiming legitimacy. Republicans of that day said the president of the Senate (the vice president) could decide which slate was proper, but Democrats protested.

Weeks of stalemate and negotiation went by before a special commission struck a deal. The Republican Rutherford B. Hayes would be president and the Democrat Samuel Tilden would concede, but in exchange, the Republicans agreed to withdraw the federal troops that had supervised Reconstruction in the readmitted Southern states since the end of the Civil War. Thereafter, the economic and political gains that had been made by emancipated African Americans in the South were largely lost — including access to the ballot.

Dissatisfaction with that election and its aftermath fueled debate over the presidential election process. Finally, nearly a dozen years later, Congress enacted the Electoral Count Act of 1887. That law has long been criticized as containing contradictions and ambiguities — some of which still afflict the process in our time.

Nixon counts for Kennedy

Among these is the continuing role of the vice president in opening the envelopes from the states that contain the reports of the Electoral College voting. The vice president is to hand these to tellers from the House and Senate "in the presence of" both chambers.

If no one objects, this is a simple matter of reading, counting and announcing. It has typically been done in well under half an hour.

Not everyone in Congress even feels compelled to attend. And even the vice president has been away: In 1969, Vice President Hubert Humphrey decided to attend the funeral of the first United Nations secretary-general instead. That meant the Senate president pro tempore, at the time Georgia Democrat Richard Russell, had the job of announcing that Humphrey, who had been his party's nominee for president, had lost the election to Republican Richard Nixon.

Eight years earlier, Nixon himself had been the vice president and had presided over the counting of the electoral votes by which he lost his White House bid to Democrat John F. Kennedy. In the course of that count, Nixon was even called upon to choose which slate of electors to honor from the new state of Hawaii. The first tabulation of votes in the islands had favored Nixon, but a recount put Kennedy ahead. So two slates were submitted, both with the governor's signature.

Hawaii had just three electoral votes at the time and those votes were not going to alter the outcome, so Nixon could smile generously and allow them to be counted for the president-elect.

Gore gavels an end to challenges

One vivid example of a discomfited vice president was provided by Al Gore, who held that office on Jan. 6, 2001, and had to read out his own Electoral College defeat (271-266). If the vote of any one of George W. Bush's 30 states had been reversed, Gore would have been the winner.

The race had been decided by the Supreme Court in December 2000, when the justices put an end to five weeks of contested counting in Florida (where the margin was just 537 votes). Gore had won the popular vote nationwide by about half a million.

On that January day in 2001, a procession of Democratic House members, including a dozen members of the Congressional Black Caucus, protested during the joint session. They spoke of alleged voter suppression in communities of color and said the votes that were cast had been miscounted. They begged for at least one senator to join them so as to force a debate and a vote on the Florida electors.

But Gore, who had conceded weeks earlier and urged Democrats in the Senate not to prolong the process, gaveled the House members down again and again.

At one point he pleaded for an end to it. When Democratic Rep. Jesse Jackson Jr. became especially impassioned, Gore stretched out his hands in a gesture of helplessness and said: "I appreciate the gentleman from Illinois, but hey ..."

When all was said and done, Gore closed the session by saying: "May God bless our new president and new vice president, and may God bless the United States of America."

Four years later, the January 2005 joint session of Congress heard the Electoral College result from Bush's reelection over Democratic Sen. John Kerry of Massachusetts (who did not attend). A House member of Ohio, Stephanie Tubbs Jones, rose to object to the count from her state. It mattered, because without Ohio's electoral votes, Bush would not have had the 270 needed to win.

Jones said there had been irregularities and defects in her state, including a lack of voting sites in communities of color. She was supported by Sen. Barbara Boxer, a Democrat from California. The House and Senate separated, debated for two hours and voted to accept the Ohio count as reported. Boxer's was the only vote to the contrary in the Senate.

In 2017, several members objected to the acceptance of the electoral vote for Trump. "Mr. President, I object because people are horrified," said Rep. Barbara Lee, D-Calif. The presiding officer was the vice president of that era, Joe Biden. He asked if the objection was being joined by a senator and was answered in the negative. "In that case," Biden said, "it cannot be entertained." Republicans in the chamber applauded.

Not the Gore approach

In the present instance, Trump has gone on goading supporters in Congress to seek to overturn the election. And he has urged activists to come to Washington on Jan. 6 for a "wild" protest.

According to Trump and key allies, their aim is not merely to express outrage but to alter the process going on inside the Capitol beginning at 1 p.m. on Wednesday. And their chances of doing that are, in effect, zero.

That may not matter to the throngs in the streets that day. But it will matter at the end of the day, at the beginning of the next and on Inauguration Day on Jan. 20.

That is because there is no further determination left to make in this election. The role of Congress is to accept and clarify what 50 states and the District of Columbia have already determined.

So what will transpire Wednesday should not be regarded as suspenseful with regard to the continuation of the government. That is a done deal. What is still at stake, however, is the attitude of Trump supporters toward the legitimacy of that done deal. As a consequence, there is also an opportunity for individuals in the Republican Party to show their fealty to Trump and thereby endear themselves to his most loyal voters.

Rep. Mo Brooks, an Alabama Republican and outspoken Trump loyalist, has said he will object to the results from swing states that went from Trump in 2016 to Biden in 2020. Dozens of other Republicans say they will do so as well. This will likely begin when the third state in the alphabetical roll call is reached. That will be Arizona, where Biden won by one of his slimmest margins.

The House objectors will need at least one senator to sign their written protests before they can force a debate and vote by the House and Senate.

But one senator, first-termer Josh Hawley of Missouri, has said he will object to the results being reported by at least one state. Eleven other Senate Republicans — seven incumbents and four newly elected in November — said Saturday they will cast protest votes as well unless Congress sets up an emergency commission to review voting procedures before Inauguration Day.

In doing so, they may cite the 1877 commission that chose Hayes over Tilden. But in that case, there were disputed slates of electors, and no one had a clear Electoral College majority. In the current instance, neither of those problems exists.

Pence has since indicated he's supportive of the electoral objections, but that does not change the limited nature of his role.

What will happen

What will happen instead is that the Democrats, who control the House, will vote to accept the Electoral College results as reported. In the Senate, at least half a dozen Republicans have said they will do the same, and they will be joined by all the Senate Democrats and both of its independents. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., acknowledged the Electoral College outcome the day after it was made official and congratulated Biden as the president-elect.

McConnell's judgment was endorsed by Republican Sen. John Thune of South Dakota. Trump responded with a tweet promising a primary challenge to Thune's next reelection bid.

That tweet offers at least a partial explanation for why so many Republicans are willing to challenge the outcome of an election on the basis of nothing but their own candidate's insistence that he could not have lost.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content