Section Branding

Header Content

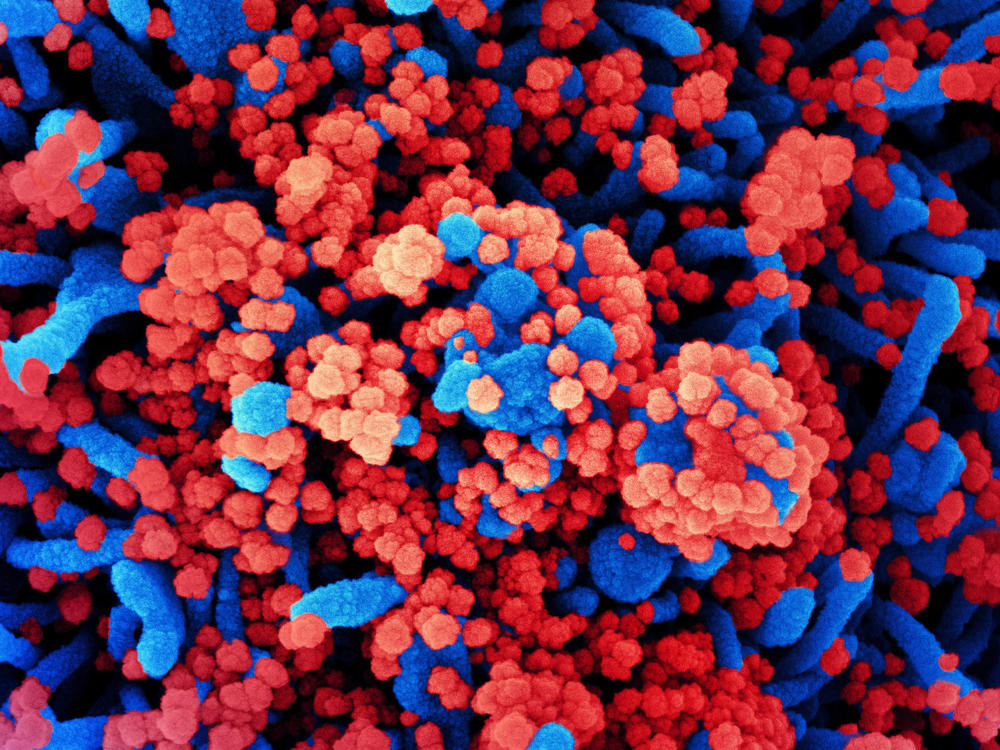

How COVID-19 Attacks The Brain And May Cause Lasting Damage

Primary Content

Early in the pandemic, people with COVID-19 began reporting an odd symptom: the loss of smell and taste.

The reason wasn't congestion. Somehow, the SARS-CoV-2 virus appeared to be affecting nerves that carry information from the nose to the brain.

That worried neurologists.

"We were afraid that SARS CoV-2 was going to invade the brain," says Dr. Gabriel de Erausquin, an investigator at the Glenn Biggs Institute for Alzheimer's and Neurodegenerative Diseases at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Their fears proved well-founded — though the damage may come from the body and brain's response to the virus rather than the virus itself.

Many patients who are hospitalized for COVID-19 are discharged with symptoms such as those associated with a brain injury. These include "forgetfulness that impairs their ability to function," de Erausquin says. "They complain about trouble with organizing their tasks, and that entails things such as being able to prepare a meal."

But COVID-19 also appears to produce many other brain-related symptoms ranging from seizures to psychosis, a team reports in the Jan. 5 issue of the journal Alzheimer's & Dementia. The team, which included de Erausquin, says severe COVID-19 may even increase a person's risk of developing Alzheimer's disease.

For many affected patients, brain function improves as they recover. But some are likely to face long-term disability, de Erausquin says.

"Even if the proportion, the rate, is not very high, the absolute number of people who will suffer these consequences is likely to be high," he says, because so many people have been infected.

Scientists are still trying to understand the many ways in which COVID-19 can damage the brain.

It's been clear since early in the pandemic that the infection can lead to blood clots that may cause a stroke. Some patients also suffer brain damage when their lungs can no longer provide enough oxygen.

To understand other, less obvious mechanisms, though, scientists needed brain tissue from patients with COVID-19 who died. And early in the pandemic they couldn't get that tissue, says Dr. Avindra Nath of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

"Because it was such an infectious organism, people were not conducting autopsies at most places," Nath says. They simply lacked the protective gear that would allow them to remove a brain safely.

That's changing, though, says Nath, who was part of a team that studied brain tissue from 19 COVID-19 patients.

The team saw widespread evidence of inflammation and damage, they reported Dec. 30 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

They also found a possible explanation for the damage.

"What we found was that the very small blood vessels in the brain were leaking," Nath says. "And it wasn't evenly — you would find a small blood vessel here and a small blood vessel there."

The injuries resembled those from a series of tiny strokes occurring in many different areas of the brain, Nath says.

The finding may explain why COVID-19 patients have such a wide range of brain-related symptoms, Nath says, including some related to brain areas that control functions such as heart rate, breathing and blood pressure.

"They complain of heart racing," he says, or that "when they stand up they get quite dizzy. Or they can have urinary problems."

Still others report feeling extreme fatigue, which can also be caused by a brain injury.

What's more, the inflammation and leaky blood vessels associated with all these symptoms may make a person's brain more vulnerable to another type of damage.

"We know that those are important in Alzheimer's disease and we're seeing them play a key role here in COVID-19," says Heather Snyder, vice president of medical and scientific operations at the Alzheimer's Association. "And what that may mean in later life, we need to be asking that question now."

So the association and researchers from more than 30 countries have formed a consortium to study the long-term effects of COVID-19 on the brain. The effort will enroll people who were hospitalized or who are already participating in international research studies of COVID-19.

Findings from that research should help answer some important questions about what happens to COVID-19 patients after an infection, Snyder says. Researchers will assess patients' "behavior, their memory, their overall function" at six-month intervals, she says.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.