Section Branding

Header Content

What 1919 Teaches Us About Pent-Up Demand

Primary Content

Editor's note: This is an excerpt of Planet Money's newsletter. You can sign up here.

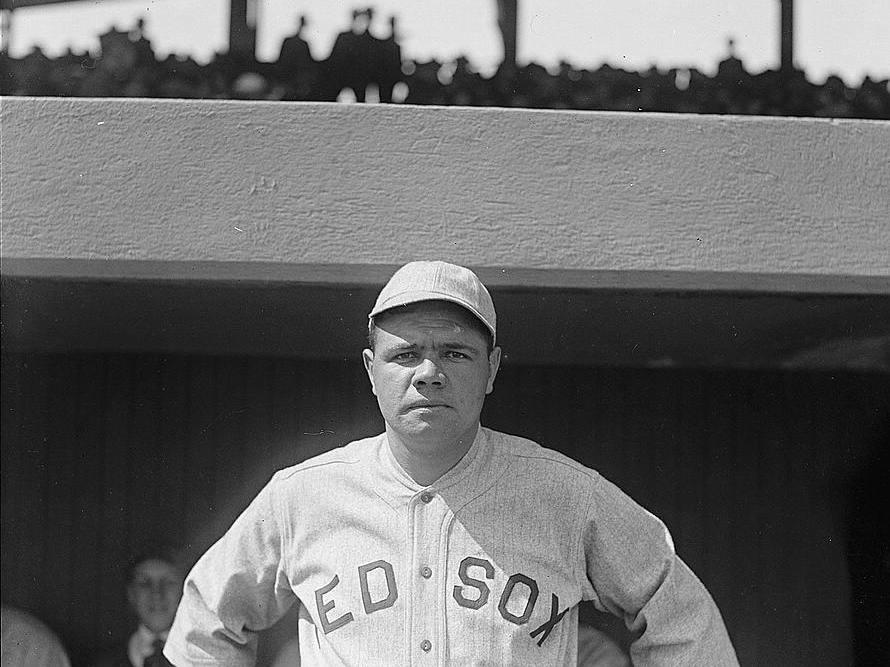

1918 should have been a great year for baseball. A young left-handed pitcher named Babe Ruth began the year by pitching an opening-day victory for the Boston Red Sox. Shortly after, Ruth lobbied the team's manager to let him play other positions so he could spend more time at the plate. The strategy paid off, and Ruth began his run as a home-run-hitting superstar, helping lead the Red Sox to the World Series.

But a world war and a deadly pandemic slashed demand to see ballgames in 1918. Just days before Ruth led the Red Sox to the World Series, soldiers returning from Europe brought a new strain of the Spanish flu to Boston, says Georgia Tech historian Johnny Smith, co-author of War Fever: Boston, Baseball, and America in the Shadow of the Great War. "Boston becomes the epicenter of a second wave, which was a more virulent strain of the virus."

Despite the Red Sox being on their way to winning the series — the last they would win before an infamous dry spell that lasted until 2004 — the flu reduced attendance at a Fenway Park that already had plenty of empty seats because of World War I. The stadium could hold 35,000 people, but for Game 5 of the Series, only 24,694 fans were in the stands. With flu cases mounting, the next day a Boston public health official warned Bostonians they should be wary of the virus. For Game 6, when the Red Sox clinched the title, only 15,238 showed up. Overall, the war and the pandemic slashed MLB game attendance by over half from what it was in the previous season.

By 1919, the war and the pandemic were over, and a tidal wave of baseball fans swelled into stadiums. Game attendance more than doubled — from 2,830,613 in 1918 to 6,532,439 in 1919. It's a classic example of what economists call "pent-up demand." After being deprived of being able to do something, when the constraints are lifted — whether because of the end of a recession, a war or a pandemic — people ravenously consume what was previously out of reach.

Now with light beginning to show at the end of the COVID-19 tunnel, the words "pent-up demand" are echoing throughout the business world. The CEO of JetBlue says pent-up demand for travel will help his company soar back to profitability. Executives at Marriott claim people will come rushing back to the company's hotel rooms. According to a recent analysis by AlphaSense, a company that uses artificial intelligence technology to sift through Securities and Exchange Commission filings, event transcripts and other business documents, use of the term "pent-up demand" is at an all-time high.

Executives in industries devastated by COVID-19 clearly want investors to believe that they're on the verge of a roaring comeback. And some evidence suggests they may be right. According to data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, the national savings rate has jumped during the pandemic, so people may have extra cash to burn on big trips, fancy cocktails and Broadway shows. And, man, do people miss going out.

According to a recent survey by the Harris Poll, 71% of Americans say they miss socializing in restaurants and bars, 61% say they miss shopping in stores and 52% say they miss movie theaters. Growing percentages of people say they're planning on splurging on vacations, clothes, cars and sporting events when things return to normal. Fifty-nine percent say they would take a COVID-19 vaccine in order to fly again. After news broke that COVID-19 vaccines work, stocks for airlines, cruise lines and other industries that rely on being face-to-face surged.

Places that have gotten the virus under control have already seen some impressive rebounds in travel and leisure. For example, in China, domestic airline travel came roaring back after the country ended its shutdowns. When Shanghai Disneyland reopened, tickets sold out in minutes.

When we get the pandemic under control, pent-up demand may even rear its head with more baby heads. For example, studies have found that after the Spanish flu reduced birthrates, countries like Norway experienced a baby boom once they recovered.

Beyond a resurgence of babies and baseball, researchers have credited the end of the Spanish flu with feeding a "speculative orgy" that helped produce a boom in 1919. Now, financial pundits predict that pent-up demand could feed a bull market this year.

But before you totally get your hopes up, the short boom that followed the Spanish flu ended in a largely forgotten crash in 1920. Only after that did we get the Roaring '20s, with the happy flappers and fedoras and all.

As for Babe Ruth — who apparently got the Spanish flu twice, by the way — he broke an American League record for home runs in a single season in the year that followed the virus. But the Red Sox then traded him to the Yankees. One season delivered a pandemic, and the next the Curse of the Bambino. Ouch.

Did you enjoy this newsletter segment? Well, it looks even better in your inbox! You can sign up here.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.