Caption

A year after Ahmaud Arbery's death, a lack of data complicates discussion about police reform in Glynn County.

Credit: The Current

A year after Ahmaud Arbery's death, a lack of data complicates discussion about police reform in Glynn County.

Deosha West grew up in Brunswick, a proud resident of the town where her father is a church leader, her mother is often found volunteering and her family name engenders respect.

The West family, left to right: Elder daughter Deosha, Pastor Darren West, his wife Effie and youngest daughter Dashekia.

That confidence, however, was shaken two years ago when West, then 28, was pulled over on Altama Avenue by a white police officer while she was driving her mother to the doctor. The reason he cited was the tint of West’s windows. A week later, the same cop in almost the exact same spot pulled her over again. He accused her of speeding, which West denied. Their exchange got heated. Then, the cop wrote her a ticket: another one for her windows, instead of the originally stated offense.

“We went to court and the ticket was thrown out by the judge, but after I was reprimanded for being difficult to the officer,” said West, who recently moved to Atlanta to work at Georgia Tech. “I’m always on the lookout for the police now.”

A year ago this week Ahmaud Arbery was allegedly killed by white men who had called police to report a suspicious Black man jogging in their neighborhood. Glynn County police who arrived on the scene didn’t perform first aid, although the critically injured 25-year-old former football standout was still breathing. A local district attorney privately concluded that no crime had occurred, despite compelling video evidence that eventually led to murder charges for three suspects.

Long before this shocking tragedy brought Brunswick and Glynn County into the national discussion about racism, many Black residents described their relationships with the majority white local law enforcement as uncomfortable, bordering on hostile. While Arbery’s death didn’t come at the hands of the police and officer-involved shootings are rare in this corner of Coastal Georgia, one of the suspects was a longtime investigator for the district attorney and someone with close ties to the police. The events from last February underscore what Blacks residents say is a historic feeling of being targeted, instead of defended. Watched, instead of being watched out for, a perception tinted by countless tales like West’s, whereby Black residents are pulled over or questioned by law enforcement because of the color of their skin, rather than for any actual wrongdoing.

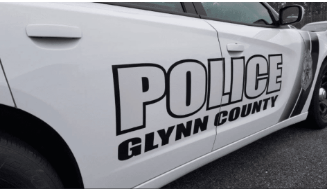

One of the most pernicious aspects about the perception of racial bias among some local law enforcement is the difficulty quantifying that view. Georgia law does not obligate police departments to record and collect data from which residents, police and policy makers could draw objective conclusions about implicit bias or racial profiling.

In the year since Arbery’s death, that opaque situation over defining, acknowledging or fixing allegations of racial bias have complicated efforts to reform the Glynn County Police, the agency that responded to the scene where Arbery was shot Feb. 23, 2020, and which has been mired in scandal for years. The department last September adopted multiple recommendations designed to improve community policing and has promoted a Black, 20-year veteran of the department as interim police chief. But that hasn’t satisfied the ardent voices from community leaders who demand more radical change.

John C. Richards, Jr., co-founder of A Better Glynn.

“There’s a lot of reform that needs to happen to help the Brunswick Police Department and the Glynn County Police Department not police the Black community in a militaristic way and instead in a more community-focused way,” said John Richards, Jr., a co-founder of A Better Glynn, a community group formed to respond to local outrage over about the handling of Arbery’s death.

Glynn County and Brunswick police forces reject allegations of implicit bias or racism in their ranks. Privately, cops have expressed outrage over Arbery’s death, and they say that the tragedy was an aberration that doesn’t reflect their effective crime fighting. Neither police force responded to requests for comment from The Current about community relations and efforts to build trust with minorities.

Crime reports in Georgia reveal the color of an arrested person’s skin and the demographics of people sentenced to jail. As of 2019 Black people comprised 60% of those incarcerated in Georgia, despite Black people being 32.4% of the overall population.

What is more difficult to discern is how often police target Blacks in their inquiries or investigations, even for procedures as straightforward as traffic stops, which is one of the few times law-abiding citizens ever interact with the police.

The Peach State is one of 27 states without laws mandating the reporting of race by police in traffic stops. Georgia also lacks laws to quantify what racial profiling by police means. The result is subjective, rather than objective, standards of what implicit or explicit bias looks like, rather than quantifiable measurements with which law enforcement and communities could hold themselves to account, says Farhang Haydari, the executive director of the Policing Project at New York University’s School of Law.

“If recent history has taught us anything, it’s that even when police act with best intentions, enforcement disproportionately falls on communities of color. This is true across the country. The status quo won’t change until legislatures step up and act. Only comprehensive state legislation can ensure the kind of transparency and accountability that is needed,” Haydari said.

Earlier this month, five Democratic lawmakers, all members of the Black Caucus, introduced a bill at the state house designed to end racial profiling by police, require data collection and annual reporting about interactions with people of color.

The legislation GA HB17 hasn’t made it to committee vote, and its future is unclear. Unlike the repeal of the citizens’ arrest law, the law cited by lawyers of Arbery’s alleged killers for their actions, HB17 has not attracted any Republican support, including from legislators from Glynn County.

Glynn County Police says it has data documenting more than 10,000 traffic stops between 2018-2020, but the force keeps no demographic data on drivers unless they are given a citation.

Black leaders pushing for police reforms in Glynn County have organized themselves into a new vocal community bloc in the months since Arbery’s slaying. One of the issues that galvanized their actions was the perceived cosy relationship between two of the men ultimately charged with Arbery’s murder, the police and the district attorney’s office.

Gregory McMichael, 64, his 34-year-old son, Travis McMichael, and their friend William Bryan were indicted last June, and each have pleaded not guilty. The elder McMichael is a retired investigator for the Brunswick District Attorney, who participated in earlier police investigations of Arbery.

Arbery’s friends and family say that while the young man did have past run-ins with law enforcement, he was also targeted by police for no apparent reason other than he was a Black man. One such incident occurred in 2017, when a white police officer patrolling a local park approached Arbery’s parked car, demanding that he submit to a search. When Arbery refused and demanded to know a reason for the police suspicions about him, the responding officer used a Taser on him.

Allen Booker, Glynn County commissioner

Commissioner Allen Booker, the only Black official on Glynn County’s Board of Commissioners, says the magnitude of historic mistrust between police and minorities mean they can’t be solved overnight. His experience as a lifelong resident of the county shows that police have never established positive relations with the Black community. That’s despite the fact that Census data shows that Brunswick’s population is 55% Black, while 34% of the country are people of color.

“We realize that there has not been a full trust of the police departments here, not in my lifetime,” said Booker, 58. “It’s not one of trust and not one where we feel they keep us safe and secure. We didn’t feel like the police were ever partners in our efforts to keep young people out of jail.”

To be sure, the county police force has struggled with a stew of problems not directly related to race well before Arbery’s death.

In 2018 the International Association of Chiefs of Police audited the Glynn County police force and issued a scathing 154-page report about how to improve policing and internal procedures.

A week after Arbery’s killing last year, a grand jury indicted then-Glynn County Police Chief John Powell and three other senior officers on 20 criminal charges including intimidating witnesses and attempting to commit a felony after a more than four-year investigation.

With such internal disarray, it is unclear to what extent, if at all, the county police have started implementing the recommendations from the operations and management audit.

One of the dozens of conclusions was that the force “consider additional training in the area of implicit bias to help continue to raise the consciousness of the force in this regard.” Another recommendation was to increase communication with the public.

Late last summer, Glynn County Board of Commissioners announced what they believed was one visible measure of progress between the police force and Black residents. They promoted Rick Evans as the force’s first-ever Black captain. A Brunswick native and 20-year veteran of the force, Evans in January then became interim police chief.

Interim Chief Rick Evans.

While Black community activists have welcomed the move, many still don’t trust that the force or the county leadership overseeing police budgets and staff is committed to deep, structural changes.

“To bring someone on that has not been an agent of change into a role without the permission or awareness of the community means you’re looking to maintain the status quo,” said Elijah Bobby Henderson, who helped found A Better Glynn.

Pastor Darron West, 51, grew up in Brunswick being told by his elders not to get caught on a certain side of town after dark. Black people, in those days, internalized a second-class status regarding police. “It has been a continued suspicion of anyone of color. One that I have experienced all of my life,” he said.

West now sits on the Community First Planning Commission, a nonprofit board that works to increase the public’s role in police reform, including reshaping police ranks to better reflect the diversity of the county.

So far, the panel’s track record with the Board of Commissioners has been mixed.

In January, the commission rejected their group’s request to hire the National Black Police Association to recruit candidates for the permanent police chief position, a move they felt would underscore the commitment to diversity as well as a chance to save taxpayer money. They had secured a grant from a Washington D.C.-based organization to pay for the recruitment process. Instead, the commission hired the Georgia Association of Police Chiefs to handle recruiting.

Carl Alexander

Then, on Feb. 11, the Glynn County commissioners voted 7-0 to hire a new police special adviser, a retired police chief named Carl Alexander, who is white. The $65,000 position puts him in charge of administrative issues, while Evans, in his interim leadership role, would concentrate on daily police operations.

Neither Evans nor the Glynn County Police have responded to requests for comment from The Current about the move. Booker has described the decision as a way to mentor Evans to gain the experience necessary to take over the job full time.

The County Commissioners and Evans both issued public statements after the vote supporting the decision.

Pastor West, who respects Evans, is reserving judgement about the wisdom of the board of commissioners’ vote. After hiring Alexander, the commissioners reversed their previous decision to shut out the Black law enforcement organization in the search for a new chief.

“We have to be cautious with how we view this promotion,” he said of Evans’ interim job. “I feel like it is something they did to quiet us down.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current, providing nonpartisan, solutions-based investigative journalism without bias, fear or favor with clear focus on issues affecting Savannah and Coastal Georgia.