Section Branding

Header Content

A Story Of Youth, Hope And Loss — And The Mystery Of COVID-19

Primary Content

The doctors didn't know what to do.

Audrey, the incapacitated young woman in the ICU, had just celebrated her 29th birthday. She was physically fit and had been in perfect health. Just six months earlier, she had run a marathon with her twin sister, Kelsey. And Audrey had always been health conscious; she worked as a transplant nurse in Denver.

The medical team — nine doctors working in unison with X-ray technicians, phlebotomists and nurses — could not explain why Audrey's heart was failing.

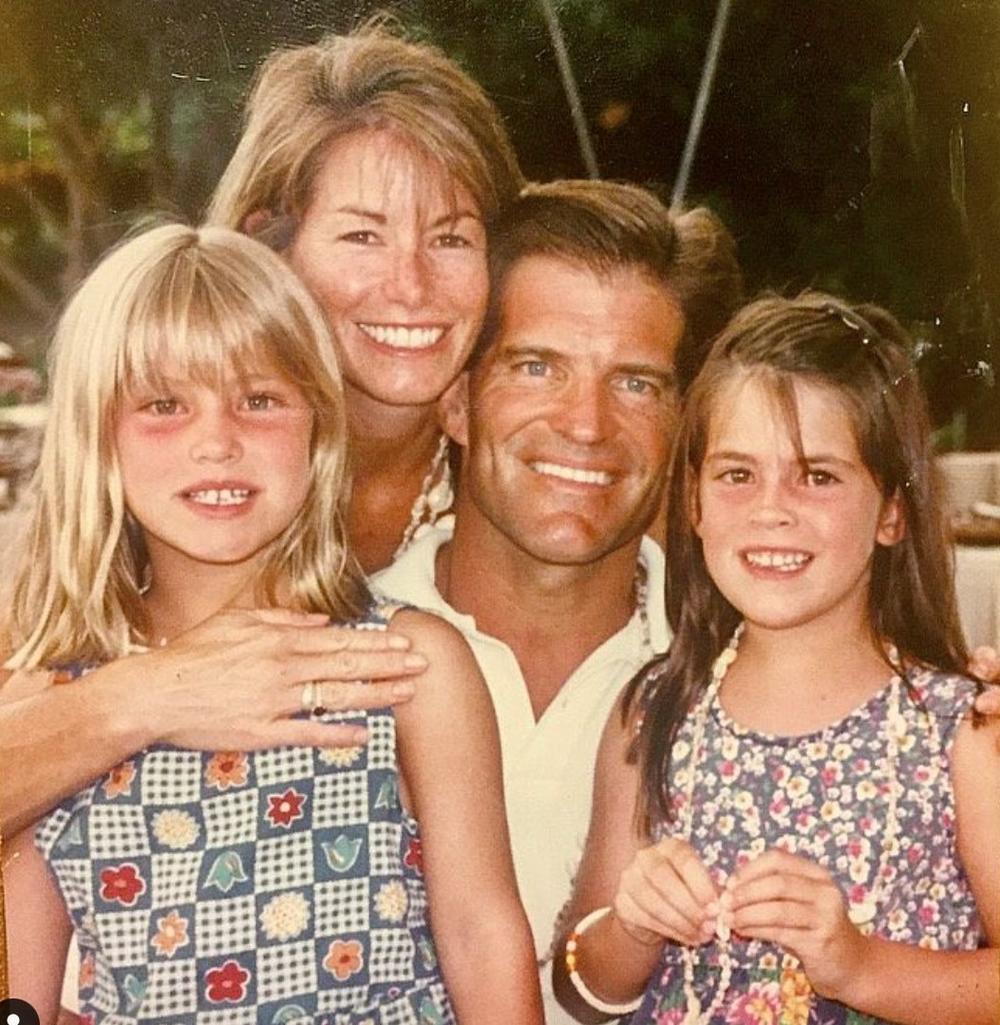

Audrey and Kelsey Ellis were born on March 17, 1991, in Berkeley, Calif. Audrey was exactly 10 minutes older. They referred to each other as "Wombie," short for wombmate. The two were inseparable in their youth, and the only time Kelsey recalls fighting with her sister was on one occasion over clothes in middle school.

Although they had gone their separate ways, the twins remained close. And last year on March 13, Audrey flew from Denver to Portland, Ore., so she and Kelsey could celebrate their birthday together. When Kelsey picked her sister up from the airport that evening, Audrey greeted her with a ludicrous, over-the-top wave and then dance-walked over to her sister. "Helloooo!" Audrey howled.

One month earlier, the World Health Organization had given a name — SARS-CoV-2 — to a highly contagious coronavirus that had originated in China and was already ravaging Europe. The same day that Audrey landed in Portland, President Donald Trump declared the coronavirus pandemic a national emergency.

Although the virus was first confirmed in the United States in January 2020, studies later would find that there were sporadic cases on the East and West coasts in December 2019, though there's no proof of widespread infection until later.

The twins had traveled to California for Thanksgiving, and both had fallen ill in early December, Audrey with what she later described to Kelsey as the worst flu of her life. She developed a fever, chills and a painful cough. Kelsey lost her sense of smell and taste and suffered from severe body aches. Kelsey's symptoms quickly passed, and Audrey's fever eventually broke.

The sisters' symptoms were consistent with the disease COVID-19, Audrey's doctors later said. But at the time, there wasn't a test for the coronavirus, and no one in the U.S. was looking for it.

Audrey never fully recovered, but she didn't have time to be sick. She was in her final weeks of graduate school, so she pushed through the pain. Her efforts paid off — she graduated with honors and received a perfect score on her nursing licensure exam. Other than a cough she couldn't kick and mild pains in her chest, she felt perfectly healthy.

"Wombies" turn 29

On the morning of March 17, Audrey and Kelsey rang in their birthday with a good cry. Kelsey said it was perfectly normal; they always cried. She was playfully frantic, raving to her sister about how big the following year would be.

"I can't believe we are going to be in our 30s — we are getting so old!" Kelsey said. Audrey's response: "You know, growing older is a privilege denied to many."

To celebrate, Audrey and Kelsey drove to Multnomah Falls, a popular hiking spot just outside Portland in the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area. The water roared as it dropped 620 feet along a sheer cliff in the dense Oregon forest. The sisters sat in the sun and watched the water for a while. Then Kelsey turned to her sister.

"I just remember looking at her and noticing something had shifted in her eyes," Kelsey said. "Then I noticed that her lips started to turn purple, and I was very worried." She suggested Audrey see a doctor before flying home to Denver later that night, but Audrey seemed hesitant. She didn't even want to leave the waterfall. "The mist is helping me breathe," she said.

Kelsey brought her sister to an urgent care center in Portland, which diagnosed Audrey with pneumonia. Audrey canceled her flight home, and Kelsey booked a room for the night to avoid putting her roommates at risk of infection.

"The last day and the last night that we spent together was our 29th birthday," Kelsey said. "We had cake. We always liked to blow out our candles together and make a wish, so that was what we did."

The following morning, March 18, Kelsey couldn't help but second-guess her sister's diagnosis. She emailed a friend whose husband was an emergency room physician. She explained Audrey's symptoms: trouble breathing, chest pain, cough, fatigue and bluish lips.

"You need to take her to the emergency room right away," her friend responded.

Kelsey rushed her sister to the Kaiser Permanente Sunnyside Medical Center in neighboring Clackamas. The drive took only about 20 minutes, but Audrey was fading. "How much further?" she asked repeatedly. The waiting area of the emergency room was empty when the sisters arrived. The hospital had prohibited visitors just one day earlier to protect patients from the coronavirus.

The security guard asked Kelsey to leave after she checked her sister in. As she made her way from the waiting room back to her car in the parking lot, every ounce of her being told her to turn around and be with Audrey. She begged the security guard, "Please, just let me wait with her." He looked around at the empty waiting room — one young woman sat alone, hunched over in pain — and agreed to let Kelsey stay.

Audrey was in agony. Kelsey rubbed her sister's back as she cried, doing what she could to reassure her that everything was going to be OK. The hospital staff finally called her name, and Audrey and Kelsey stood up and hugged each other. "I love you, Wombie," Audrey whispered. She apologized to the staff for the mud on her boots, caked on from their birthday adventures the day before, as she left the waiting room.

"I actually had this sinking feeling in my stomach. I didn't want to leave the hospital," Kelsey said. She sat outside in the parking lot for eight hours.

A medical mystery presents itself

Last March, little was known about COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. Patients typically developed an upper respiratory illness that could progress into a lower respiratory illness causing pneumonia. People either got better or got very sick and sometimes died.

Audrey was tested for the coronavirus, but her results came back negative.

Dr. Christine Choo, a critical care physician at the Sunnyside Medical Center, said Audrey had no preexisting conditions. They ran tests for autoimmune disorders and cancers; nothing. Audrey had spent several months living and working in Africa the previous fall, so the doctors tested her for everything and anything she could have contracted overseas; nothing.

But the doctors realized Audrey's condition was significantly worse than anyone had initially thought — her heart was failing. Dr. Lori McMullan, a cardiovascular disease specialist, was called in to take a closer look at Audrey. When McMullan arrived in the emergency room around 4 p.m., she found Audrey sitting in her bed, hunched over and in tears.

"I can't breathe," she cried. "I'm scared." Audrey grabbed McMullan by the hand and gave her a hug as she wept. The doctor listened to Audrey's story and looked at the data. It was very, very bad.

"When I saw her on [March 18], I hoped she would live, but I knew she probably wouldn't live through that hospitalization," McMullan said later.

Since December, Audrey had felt winded and short of breath. She was so young and her body so strong that she was unaware that fluid had built up around her lungs and heart. McMullan suspects Audrey had developed pulmonary veno-occlusive disease, or PVOD. The disease is incredibly rare, so much so that the cardiologists at the hospital had never seen it before, McMullan said.

PVOD, McMullan explained, acts as an impediment, a bottleneck situation in the body. When Audrey was sick in December, McMullan concluded, her lungs built up scar tissue that restricted blood flow in the lungs and resulted in pulmonary hypertension — high blood pressure.

The restricted blood flow put additional stress on the right side of the heart, which pumps oxygen-poor blood from the body into the lungs. To keep up with the body's need for oxygen, Audrey's heart worked overtime, all day every day, for approximately three months.

In younger patients, the body can overcome and work through these ailments, at least for a while. "Their bodies can compensate very well for a very long amount of time, and they can hide bad things brewing in their body," McMullan explained. "When they finally do come in ... they're at that breaking point."

"She's not out of the woods"

Kelsey waited in the parking lot, unaware of the severity of her sister's condition. She thought Audrey would be released before the end of the day and had hoped to avoid making two trips to the hospital. Instead, Audrey texted her sister, instructing her to go back to her room for the night. They were moving Audrey to the intensive care unit. She would not be leaving anytime soon.

The twins' mother, Janine, landed in Portland just after 9 that same evening. The gravity of the situation had set in, and she instinctively hurried to be there for both of her daughters. Their father, Scott, wanted to be there as well, but the couple ultimately decided someone should hold down things at home in the Bay Area. Audrey, they assumed, would be sent home soon, a few days spent recovering at the hospital at most. Someone needed to ensure the house was ready for her return and pick the family up from the airport.

The following morning, Kelsey joined her mother in downtown Portland, about half an hour's drive from the hospital. Janine would have bunked with Kelsey, but it wasn't clear whether it was safe to do so. Instead, she booked a room in the city, and Kelsey wore a mask when they greeted each other outside.

One of the doctors reached out to give Kelsey an update: "She's not out of the woods."

The night before had not gone well for Audrey. She told Kelsey how she couldn't breathe and that it was painful for her to lie down because it caused her lungs to fill up with fluid. Her heart raced to keep up with her body's demand, which produced more fluid and further compressed the heart.

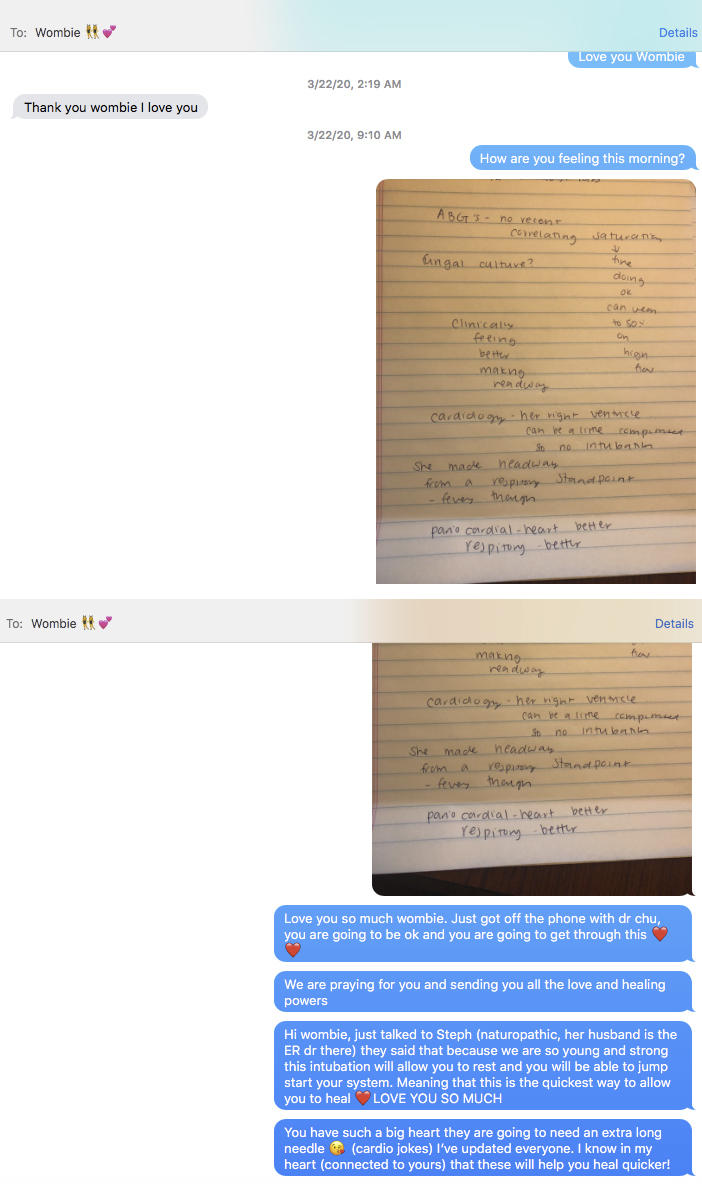

Kelsey and Janine sent Audrey voice messages so she could listen to words of endearment without feeling obligated to respond, Kelsey said. They also managed several video calls with each other.

Seeing Audrey in the hospital was difficult: Her sun-kissed skin had turned pale; she looked exhausted, and her eyes seemed to struggle to stay open; she had a breathing apparatus attached to her nose, with tubes connected to a machine that forced oxygen into her lungs; electrodes that monitored her heart peeked out of her hospital gown, the wires twisted; IVs delivered fluids and critical antibiotics to her bloodstream. Somehow, she still managed to smile in photographs.

"I'm crying cause I want you in here to hold my hand and brush my hair," Audrey texted her sister. "I know. ... This is so, so hard not to be there," Kelsey texted back. "You and I are connected."

On March 20, Day 3, Audrey showed minor progress. She required less oxygen, and the fluid levels in her heart and lungs dropped. Audrey was able to stand at the edge of her bed later that afternoon, an immense accomplishment at the time.

Her condition continued to improve. On Day 4, she was able to sit up in a chair on her own and enjoyed a strawberry smoothie that one of the nurses had made just for her.

"She just went on and on about how caring and thoughtful the nurses were that cared for her. She loves strawberries. They went out of their way to give her that," Kelsey recalled. "And then the night of the 21st was when she started to kind of go downhill."

Waiting and praying

Daily echocardiograms — ultrasound images of the heart — revealed that even though her oxygen levels had improved, fluid continued to build up in the pericardium, the sac that surrounds the heart. It compressed Audrey's heart and prevented blood from circulating. Her condition worsened.

The situation quickly transitioned from treatment to a rescue operation. Choo and McMullan decided Audrey's best chance for survival would require pericardiocentesis. McMullan would plunge a needle through Audrey's chest, puncturing the protective sac, and insert a catheter to drain the fluid.

"If we tried to intubate her before removing the fluid from the space between the heart and the heart sac, she would die," Choo said. "So we created a coordinated system where we had two teams ready to go in sequence: the cardiac team to remove the fluid and as soon as the fluid was removed, then put her on the ventilator so that she could have respiratory support."

Choo called Kelsey and Janine and carefully went over the plan, explaining that Audrey had already agreed to the procedure.

"At that point, no one really knew what intubation meant. I just thought that that was like a positive thing, you know?" Kelsey said. "She would be put on a breathing machine, and she would have a better chance at recovering after giving her body a break or a rest."

Audrey was able to have a video call with her sister before the doctors sedated her for the procedure. She was calm. Audrey never wanted anyone to worry, especially on her account, according to Kelsey. "This is the last time we're going to be able to talk," Audrey said. It was 2 p.m. on a Sunday.

The doctors drained the fluid around Audrey's heart, but things were worse than predicted. As they were pulling the fluid from the sac surrounding the heart, an echocardiogram showed the right ventricle — the part of the heart connected to the lungs — expanding like a balloon.

"The right ventricle became so large that it was literally smushing the left ventricle, and the left ventricle is what gives blood flow to the brain, to your whole body," McMullan said. "This [was] rare. In fact, it never happens."

Audrey's breathing intensified and her heart rate climbed as Choo intubated her. Her heart was beating at 120 beats per minute, then 130, pounding, struggling to pump blood to the rest of her body. Her heartbeat became erratic and caused her circulatory system to collapse. Audrey's hands and feet became cold to the touch. Audrey was dying.

McMullan decided the last, best effort to save Audrey was to deploy an Impella, a small heart pump that would pull blood from the right side of the heart to the main pulmonary artery to deliver blood and oxygen to the rest of the body. The device is typically used on the left side of the heart, McMullan explained. Audrey was the first case the doctors had seen where the device would be inserted on the right side; nobody at the hospital had done the procedure before. The doctor charged with the task watched a YouTube video to ensure he had everything right.

Meanwhile, in downtown Portland, Kelsey and her mother continued to wait, and pray. The hospital called to update them about Audrey's condition. "We were literally just receiving call after call of just terrible news," Kelsey said. "It all felt surreal, like it was just a terrible dream, a worst nightmare."

Audrey was rushed to the operating room, and the Impella was inserted into her right femoral vein. It was guided into her heart and started pumping blood to the rest of Audrey's body. Two machines worked to save her life, the ventilator and now the Impella. Both devices, Choo explained, are used as a bridge between a critical condition and recovery.

In Audrey's case, there would be no recovery.

Her heart, as strong as it had been, was spent. Her liver, pancreas and kidneys stopped functioning because of the lack of circulation. The heart's electrical system became chaotic and developed irregular rhythms called ventricular fibrillation.

"Her heart had stretched out to an extent that was not compatible with life," Choo said. Instead of pumping, the heart merely quivered, and then finally stopped.

Built-in best friends for life

Kelsey and Audrey were connected. "Twintuition," as it's often called. Since the day they were born, both sisters seemed to sense when something was wrong with the other. Kelsey paced outside her mother's hotel, awaiting an update from the doctors, when she felt a "knock" on her heart.

"I just stopped in my tracks and just thought to myself, 'Oh, my God, this can't be happening,' " Kelsey said. "I just kept saying over and over again, 'Audrey, you're going to be OK. You know, you're strong, you're healthy.' "

Kelsey began to panic as she walked across the courtyard to her mother. Janine's phone was about to run out of battery power, so they went up to her hotel room to charge it. It rang moments later. It was Choo. "I'm so sorry. We lost her."

Audrey Marie Ellis passed away from multiple organ failure at 5:25 p.m. on March 22, 2020. The hospital was devastated by her death.

"There must've been about 40 people who came up to me to express their grief," Choo said. "Telling Kelsey and her mother, and then later her father, the news of her death was one of the most difficult things that I've had to do as a physician, especially when they could not be with her."

Kelsey and her mother drove to the hospital to see Audrey one last time and to say goodbye. Even in death, Audrey was beautiful, Kelsey said. The following day, Kelsey and her mother boarded a flight back to California to be with Scott. Kelsey returned to Portland several weeks later to bring her sister's remains home.

In the weeks following Audrey's death, Choo and her colleagues heard about patients across the country dying of right-sided heart failure weeks and months after a coronavirus infection. Additionally, a study conducted in Frankfurt, Germany, last summer found that out of 100 recovering COVID-19 patients — 67 of whom were healthy enough to recover at home — 60% had evidence of inflammation of the heart.

"Back in March, we thought that COVID-19 was just a short-term acute illness without the chronic effects," Choo said. "And now we're learning that people are living with brain effects, heart effects, lung effects, lasting months and even now up to almost a year."

"When the German study came out in July, we discussed [Audrey's] case with the cardiology team and came to the conclusion that she had also had heart failure as a sequela of COVID-19 infection," Choo said. "Her death certificate does not state COVID disease, so she is not included in the datasets."

Dr. Clyde Yancy, a professor of medicine and the chief of cardiology at Northwestern University's Feinberg School of Medicine, published an editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association after reviewing the Frankfurt study. More research would be needed to confirm the findings, he wrote, but the results were worrisome.

"These data suggest, preliminarily so, that in people who have been infected in COVID-19, even when cardiac involvement isn't clear at the outset, there is a relatively high likelihood that there may be cardiac involvement weeks to months afterwards," Yancy said. "If so, that means we have to deal with that whole scenario very carefully, because if it's true myocarditis, that exposes a risk — short term for irregular heart rhythms and long term for heart weakening."

Although new coronavirus cases are declining and millions of doses of vaccine are being administered every week, people need to remain vigilant, Yancy said. It's important for individuals to listen to their body and realize some symptoms might not be benign. "Don't panic, but stay engaged with your health care provider," Yancy said.

Choo, the critical care physician who worked so hard to save Audrey, is mentally exhausted. Since mid-January, she has traveled back and forth from Portland to Los Angeles every two weeks to help hospitals overwhelmed with coronavirus patients. She recently finished her final rotation, or so she hopes.

Every day, she has had to call patients' families with updates as their loved ones teeter between life and death in the hospital. Many of the patients are hooked up to ventilators for weeks, sometimes months, and although the families pray for the best, each time the phone rings they fear the worst, Choo said.

"I started my training in the AIDS era in New York City, where I was seeing young people die of AIDS, and everyone who had AIDS died. And I thought that was going to be my career-defining illness," said Choo. "COVID-19 has blown AIDS out of the water for me. I've never seen anything like this."

Learning to live with loss

"Life is a classroom," Audrey often told Kelsey. "We are here to make a difference and to learn our lessons."

But it can be hard to recognize what lessons we are supposed to walk away with, especially when we are forced to take classes we never wanted to. Like how long a cremation takes, how to pick up an urn from a drive-through window at a funeral home or the procedure for checking in human remains at the airport.

"She would always just be like, 'What is this meant to teach you? How are you going to grow from this? How can you help others through this experience?' " Kelsey said. "I kind of hear her voice in my head saying that as I'm moving through this impossible life experience."

Kelsey just moved back to the Bay Area; she's happy to be close to her parents again. Audrey's family recently established the Audrey Marie Ellis Foundation, which they hope will, in time, financially support aspiring health care workers.

On March 17, Kelsey will turn 30, an event she jokingly panicked about with her sister last year. Audrey and Kelsey called each other their built-in best friends for life. They never spent a birthday apart — one more heartbreaking first Kelsey will have to face.

"Don't regret growing older," Kelsey reminds herself, guidance received from her sister. Looking back on it now, Kelsey laughed, Audrey came out on top —she never had to leave her 20s.

Kelsey spends a lot of her time surfing. The drive to Half Moon Bay from her parents' house in Walnut Creek takes about an hour. Kelsey listens to music that Audrey had enjoyed as she drives, including a playlist called Green Eyes and a Heart of Gold, the last playlist Audrey assembled before she passed. It's full of songs about living life to the fullest.

When Kelsey gets to the beach, she does her best to leave her heartache on the shore, paddling through the waves, one stroke after another.

She replays events over and over again while she waits for the waves to come. When they do, she often lets one roll by, imagining Audrey surfing with her, before taking one for herself. Somehow, it always makes Kelsey feel better.

She reflects upon her sister's words as she waits for the next set to come in: "What is this meant to teach you?"

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Correction

An earlier version of this story misspelled Lori McMullan's last name as McMullen. Also, Audrey Ellis' date of death, March 22, 2020, was misstated as March 20, 2020.