Section Branding

Header Content

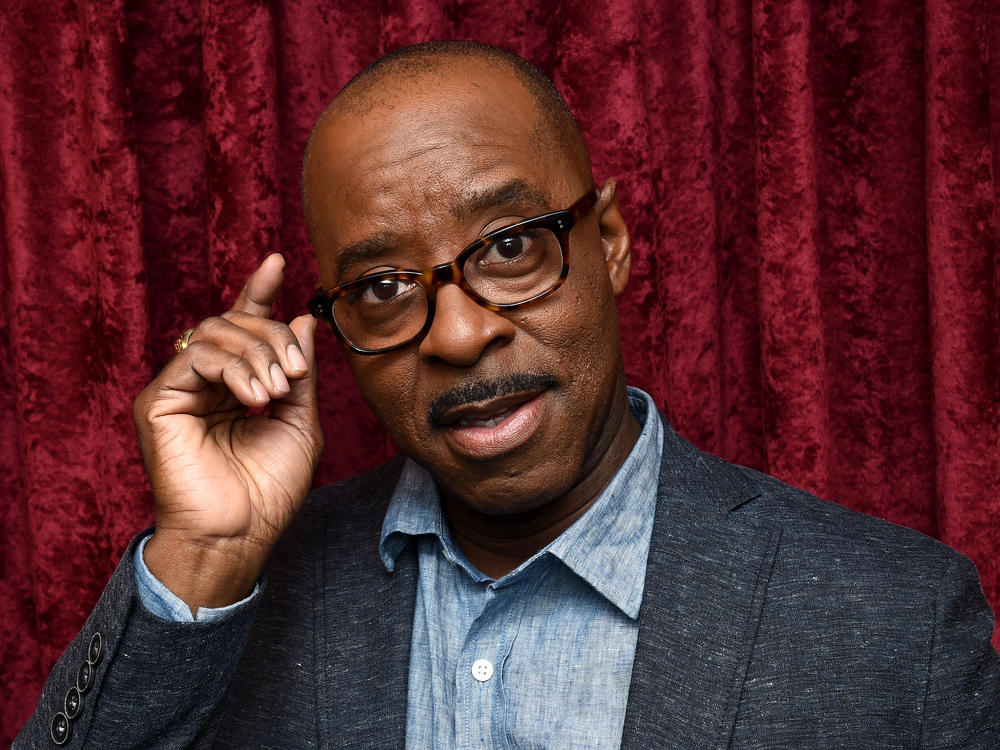

Acting Is 'Problem Solving,' Says Courtney B. Vance

Primary Content

Before she became a superstar, Aretha Franklin was a girl who sang gospel in her father's church in Detroit. Her father, Rev. C.L. Franklin, was a preacher who became known for the radio broadcasts and albums of his sermons. When the Rev. Franklin was establishing himself in the 1950s, he toured the Deep South gospel circuit with his gospel caravan — and, when Aretha was 12, he took her along as a performer.

Actor Courtney B. Vance plays Rev. Franklin in the National Geographic series, Genius: Aretha, now streaming on Hulu, which chronicles the conflicts that developed between father and daughter. For Vance, playing Aretha's father was a chance to reconnect to his own roots. He grew up "churched," in Detroit, with music all around.

"As children, we used to run down the street on the grass and just go sit on [Motown headquarters'] Hitsville steps and watch people coming in and out," he says. "Knowing what I know now about [Aretha Franklin], her life, it's amazing to me that she was able to keep going for years. ... Seven years she was ... trying to make it before she was able to get on the charts."

Vance was also inspired by Rev. Franklin's own unlikely path to success. When the Reverend's stepfather, who had been a sharecropper, made him choose between "the pulpit or the plow," Rev. Franklin chose the pulpit.

"And the stepfather kicked him out," Vance says. "So [C.L. Franklin] had to sink or swim. There was no safety net for him. And to see the heights that he reached after that very fateful day, to me, was everything."

Interview highlights

On capturing Rev. C.L. Franklin's voice and how he savored words

Repetition was and is that Black tradition of call and response, and it ties everyone together. It ties the choir behind him together with the congregation in front of him. And he's enveloped in sound and in family and everybody knows what they're supposed to do. There's a person who gives the repetition of certain words. And so it is a rhythm. It's a rhythm that just builds. I listened to hundreds of sermons of his because they're all digitized online. And so I listen just to hear his cadence, his rhythm, his words that give me key words that keep me in sync with him.

On C.L. Franklin's many affairs and that he allegedly impregnated a 12 year old in Memphis

It's tricky. [Him] impregnating a 12 year old Memphis was true. ... When you look at the time period, judging C.L. Franklin and anyone with 2021 eyes is a little challenging, because anyone who came out of that degradation, out of that horror that was sharecropping South and headed North was scarred. And the people who were harmed were — who were taken advantage of by white and Black men — were Black children and Black women. So I look at that as I begin my journey with C.L. Franklin, knowing that everybody of color was harmed. You don't know a person until you're in their shoes and there's nowhere for them to go and they get no relief from their pain and they turn to the innocent ones. Is it right? Was it right? No! But it happened. I know that he's a human being and human beings are flawed.

On how he prepared to play O.J. Simpson's defense attorney Johnnie Cochran in The People v. O.J. Simpson — and why he chose not to re-watch videos of Simpson's trial

The way I approach acting is it's problem solving, and sometimes based on who I am, the problem needs to be solved by delving into and doing all of the research and doing all of the minutiae work and building from scratch. But with Johnnie Cochran and People v. O.J., I said, ... I'm just going to read ... Jeffrey Toobin's [book, The Run of His Life] and I'm going to stay away from watching footage. If I'm watching footage, I'm mimicking. And I had to get to the place where I'm doing it and the scripts are great and people will forgive the minutiae that I miss because they'll get wrapped up in the story. And I'm going to jump in. ...

I saw that [Cochran's] mother, of her four or five children in his family, she chose him, she knew that he would have the stomach to deal with white folks, and so she put him in an all-white environment and went to L.A. High and then he went to UCLA and the rest is history. So once I saw that — that he was put in an all-white world — and used that to segue out into his life and his career, [I thought] "God, I know him." That was my journey: Scholarship to Detroit Country Day, Harvard, Yale, Fences [on Broadway]. Once I knew that, I said, "I got him. I don't need anything else."

On growing up in Detroit and witnessing the effects of white flight on the city

That was a very heady time. I was just starting to become, "aware." I was 9 the summer of Mayor Coleman Young, the first Black, African American mayor of Detroit ... told white folks, "We don't need you, get out." And Detroit was a super segregated city like Chicago, St. Louis, and for years people, the police, could do what they wanted to Black people. And they did. And Black folks were tired of it. And when they got their Black mayor, they said, "Get out."

I mean, it literally was a battle for the soul of Detroit. And for the first time, Black folks had won a battle. And it didn't go the direction that we would hope it would have gone and the city would have kept climbing. White folks, a tax base left the city, leaving ... predominantly just Black folks there. So it used to be a million and a half folks, cosmopolitan Detroit, and it started to dwindle. And when the tax base leaves, the good schools go. And so it wasn't a good situation and the city never really recovered from it. ...

The neighborhood where we grew up was all white, and a smattering of Blacks, when we came in, and our parents were so happy. We had a five bedroom house. We had made it, you know, the deluxe apartment in the sky, moving on up. But we got there and we saw it happen in front of our eyes that the neighborhood flipped overnight. That summer of '69, the white folks left. And my parents realized they'd never get their money out of the house. The school flipped to do an all-Black school. And we were great students. But eventually the peer pressure shifted from getting great grades, which we always did, [to] what you were wearing. And we started fighting and our parents, in the middle of the semester, pulled us out and put us in a Catholic school, an all-white world, and which was completely frightening and foreign to us. But we had to figure it out really quickly and get to the business of school.

On how being under the tutelage of Lloyd Richards, the Black dean of the Yale Drama School, changed his career

I was blessed; I was at Yale at the time when Lloyd Richards was there and he was the artistic director of Yale Drama School, the Dean of Yale Drama School. ... And so the playwriting world centered around him. ... My wife, Angela Bassett was there ... she was his first class. ... Lloyd had set up around the relationships around the country [with] regional theaters and ... had a toolbox full of scripts so that he could take the scripts and develop them and have them go around to the various regional theaters. And so it was a world that had never existed before. And we were in the center of it.

It was interesting being at Yale ... And it was an amazing time to be a Black guy because I was introduced into the world with [August Wilson's play] Fences. ... I owe my career to Lloyd Richards.

Lauren Krenzel and Kayla Lattimore produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Beth Novey adapted it for the Web.

Copyright 2021 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.